ISSN : 1598-2939

ISSN : 1598-2939

ⓒ Korea Institute of Sport Science

The purpose of this study was to identify effective strategies for life skill development utilized by coaches. Ten (10) veteran football coaches were recruited and interviewed. Each interview lasted approximately for two hours. All recorded data were transcribed verbatim and later used for further analyses. The results were presented in 13 parts organized by key interview foci: the role of academic coach; the typical day of academic coach; key components for program success; the goals of the academic coach; success stories; effective strategies; ineffective strategies; strengths of academic coaches; weaknesses of academic coaches; strengths of the program; limits of the program; gender/ethnic issues; and recommendations for future academic coaches. Positive youth development strategies were categorized into two hierarchical levels. One is global macro level strategies and the other is specific micro level ones. Based on the interviews, a number of youth development strategies, both in macro and micro level, perceived to be effective were identified. However, it should be noted that while the coaches perceived these strategies were effective, they were not viewed as a panacea for all athletes in all situations. Finally, based on findings from the current study, a model for effective life skills development strategies was proposed

The purpose of this study was to identify effective strategies for life skill development utilized by coaches. Ten (10) veteran football coaches were recruited and interviewed. Each interview lasted approximately for two hours. All recorded data were transcribed verbatim and later used for further analyses. The results were presented in 13 parts organized by key interview foci: the role of academic coach; the typical day of academic coach; key components for program success; the goals of the academic coach; success stories; effective strategies; ineffective strategies; strengths of academic coaches; weaknesses of academic coaches; strengths of the program; limits of the program; gender/ethnic issues; and recommendations for future academic coaches. Positive youth development strategies were categorized into two hierarchical levels. One is global macro level strategies and the other is specific micro level ones. Based on the interviews, a number of youth development strategies, both in macro and micro level, perceived to be effective were identified. However, it should be noted that while the coaches perceived these strategies were effective, they were not viewed as a panacea for all athletes in all situations. Finally, based on findings from the current study, a model for effective life skills development strategies was proposed

Positive adult-youth relationships have been identified as a key ingredient for effective PYD (Positive Youth Development) programs (Barnett, Small, & Smith, 1992; Bredemeier & Shields, 1992; Roth & Brooks-Gunn, 2015; Vallerand, Deshaies, & Cuerrier, 1997). It is well documented that relationships with caring adults are a key factor in promoting positive outcomes for youth (Brustad, 1993; Brustad, 1996; Griffith & Larson, 2015; Halsall, Kendellen, Bean, & Forneris, 2016; Miller, Bredemeier, & Shields, 1997). However, only a few studies have examined coaches’ characteristics and their strategies that may influence the development of positive outcomes (Taniguchi, Widmer, Duerden & Draper, 2009)

Steven Danish and his colleagues (1995) propose a life developmental model using psychological methods to develop life skills. Heavily focused on goal setting (i.e., how to identify, set, and attain goals), the central mission of the model is to develop personal competence. According to the model, personal competence is defined as the ability to do life planning, be self-reliant and seek the resources of others (Danish, Petitpas, & Hale, 1995). One of the unique points that this model claims is that skills learned from sport can be transferred into other life domains. While maintaining a skeptical stance on automatic transfer, they suggest several factors and characteristics that can induce the generalization of skills.

Despite many positive skills that are claimed to be instilled in program participants, there have been relatively few systematic attempts to assess the effectiveness of these programs (Danish & Nellen, 1997). Other than the fact that those life skills development programs have been well-received by funding organizations and communities, whether those programs actually produce children who have mastered those positive psychological and life skills have not been extensively studied (Cummings, 1998; Gould & Carson, 2008). Most evaluative schemes within these programs fall short in terms of assessing fundamental changes in behaviors and attitudes (Petlichkoff, 2001). Typical evaluation questions ask whether participants have learned how to set goals or whether they are willing to recommend the program to others. Furthermore, some physical educators have questioned the impact of relatively short-lived programs. While many youth development programs last for more than a year and sometimes for several years before they observe any meaningful changes in their program participants, these life skills programs last for only three to six months. In general, these normative, self-descriptive evaluative schemes regarding the effectiveness of these life skills programs have failed to substantiate their claims in developing life skills for youngsters through sport.

In summary, although there have been abundant anecdotes and testimonials about positive experiences with these youth sport programs, systematic approaches to assess how and why those programs work are generally lacking. Most youth development programs started with common sense, good intentions, and altruistic passion, without systematic evaluative schemes in mind (Romance, Weiss, & Bockovan, 1986; Smith & Smoll, 1995; Smoll & Smith, 1998).

One of the few life skills through sport programs that has been evaluated is the Play It Smart program. Play It Smart is a school-based program funded by the National Football Foundation (NFF) and National Football League (NFL) that is designed to use football experience as a tool to enhance the academic, athletic, and overall personal development of high school student-athletes (Petitpas, 2001; Petitpas & Champagne, 2000). This is done by placing academic counselors with each football team. These individuals spend about 20 hours a week running study halls, monitoring academic progress of student-athletes, providing one-on-one counseling with players, and coordinating the team’s community service activities. During a two-year pilot period, four football programs located in inner-city environments where family and community supports were minimal were selected. The vast majority of the participants were minority youth and lived in neighborhoods with high crime rates. Initial program evaluation results showed promising improvements in both players’ academic and athletic potential. Specifically, participants’ grade point averages increased from 2.16 to 2.54 (17.6%), higher than the general school average of 2.25. The scholastic Aptitude Test scores of participants also increased by 30 points (829.86 on average) and 98% of the participants graduated on time (Petitpas, 2001). Moreover, players participating in the program contributed 1,745 hours of community service work. Because of the demonstrated effect of the two-year pilot project, the program was expanded to 28 high schools nationwide.

Central to the Play It Smart program success is the introduction of an academic coach. Spending half of their working week with the team, the academic coach carries out dual roles – assisting the head football coach and counseling players. He or she is the assistant to head coach who specializes in providing a continuing link between school and football. The academic coach helps the players establish personal and team goals, monitors goal completion and progress, and provides resources that will help them achieve their goals.

While academic coaches are critical to the program, what makes these individuals effective remains unknown. What works for these counselors and what does not? The strategies used by the counselors have not been identified. A need exists, then, to study this program to identify successful strategies used by academic coaches especially in the light of its program effectiveness. Therefore, the aim of this study is to identify effective strategies for life skill development utilized by coaches.

To achieve the research objectives a qualitative interview study was conducted. Specifically, 10 academic coaches participated in in-depth interviews, focusing on the strategies they used as an academic coach, the general effectiveness of these strategies, and factors influencing their effectiveness. The sample for this study consisted of 5 male and 5 female coaches. Five were African American and five were Anglo American. In sampling the participants, proportions between gender and ace were considered.

A qualitative interview methodology (Patton, 2015) was the method of choice in this study for several reasons. First, a qualitative approach was employed because of the complex nature of the topic. Identifying effective strategies in the youth development context is an extremely challenging task. Second, theoretical frameworks for explaining effective youth development strategies are lacking. Therefore, the topic needs to be explored rather than examined from predetermined perspectives (Creswell, 1998). Third, an interview study was designed because of the need to present a detailed view of the topic. Consequently, this study seeks “thick descriptions” (Geertz, 1973) to provide rich characterizations of the current phenomena (Sparkes & Smith, 2014; Strean, 1998).

The participants were selected based on program coordinator’s recommendations of who would be most informative relative to the research questions. With the help of the associate director and commissioner of research at NFF, and the director of the program, possible participants (n=20) were initially identified. After the purposeful sampling (i.e., identifying the more experienced academic coaches with diverse race and gender), initial contact was made during a weeklong summer training program held at a local college. All ten coaches approached by the researcher agreed to participate in the study. After completing the informed consent form, a background information questionnaire was given to the participants. The background questionnaire included basic information such as previous experiences in working with athletes, educational background, and team and environmental backgrounds. In addition, perceived success rates of the academic coaches regarding their impact on various life skills (e.g., emotional control, goal setting, etc.) were assessed. An informed consent form was also collected at the same time. Verbal permission to audiotape the interview was obtained right before the individual participations. Finally, semi-structured interviews were conducted with all interviews being audio recorded.

An interview guide was developed based on the review of the literature as well as the previous research experiences with high school coaches (Gould, Collins, Lauer, & Chung, 2007). Specifically, there were 8 sections in the interview guide: (1) coaching environment (e.g., describe your typical day as a coach); (2) goals of academic coaching (e.g., what are you trying to achieve with you players?); (3) success and failure stories (e.g., describe a player who has been successful relative to meeting one’s coaching goals?); (4) effective and ineffective strategies (e.g., describe what you did with successful and unsuccessful cases); (5) characteristics of effective coach (e.g., relative to achieving your goals, what are your strengths or weaknesses?); (6) characteristics of effective program (e.g., can you tell me what are the strengths of your program?); (7) ethnic and gender issues (e.g., is being a White or Black influencing your effectiveness as a coach?); and (8) recommendations (e.g., what would you recommend to future coaches to be better prepared?) .

The sections of the interview guide and the specific questions within them were included in light of the purposes of this study. Specifically, questions pertaining to both effective and ineffective strategies that the academic coaches previously used to achieve their own academic coaching goals were asked. Moreover, factors that influenced their effectiveness as an academic coach (e.g., player, coaching staff, parents, school, and community) were addressed.

All interviews were audiotaped and transcribed verbatim by the researcher. Each interview lasted approximately 60 to 90 minutes and produced 12 to 21 pages of transcripts. The researcher then read and reread the transcripts until he became familiar with the data.

After initial reading of interview, an individual academic coach profile consisted of a 7 to 10 page summary of the interview was produced. Background information obtained from the background questionnaire was incorporated during this stage. At this point, each profile was reviewed by the coach. The profiles were designed to give an overall picture of the participant’s experience as an academic coach before the interviews were analyzed into specific themes.

After the profiles were completed a content analysis was conducted. First, each interview transcript was converted to an excel file. Each Excel file contained three columns: line number, raw quote, and a blank space for initial coding. After the initial coding sheets (i.e., an excel print-out with three columns) were set, the entire interviews were read and coded into various dimensions such as coaching environment, characteristics of effective coach, effective and ineffective strategies, factors facilitating or hindering coaching effectiveness, and recommendation. The next step was to sort each interview based on the initial higher order dimensions and produce second step coding sheets. The second coding sheets were similar to the initial coding sheets including three columns: line number, raw quotes, and a blank space for the themes (i.e., meaningful units). However, they were organized into subtitles (i.e., dimensions such as effective strategies, role of academic coaches, strengths of academic coaches, etc.). The researcher read the second coding sheets and coded each line into a meaningful label. For example, if the raw line under the factors facilitating coaching effectiveness dimension was read as “my head coach supported me tremendously” then the line would be coded into “head coach support”. After the second coding (i.e., lower order theme labeling) was completed, all data from 10 interviews were merged into a master-coding sheet. Consequently, each dimension produced one master-coding sheet. The master-coding sheet contained 11 columns with the first column being the labels from the second coding and the remaining 10 columns for the 10 coaches. The researcher read the master-coding sheet for each dimension and created a conceptual map for each dimension relative to the closeness and frequencies of those themes. The conceptual map included lower order themes, higher order themes, and categories (i.e., a conceptual level between higher order themes and dimensions). It should be noted that the numbers of levels for the hierarchical analysis differ depending on the complexity of the data.

The purpose of identifying patterns across the coaches’ interviews was to examine common themes shared by 10 coaches. The results from these analyses are presented in 13 parts organized by key interview foci: the role of academic coach; the typical day of academic coach; key components for program success; the goals of the academic coach; success stories; effective strategies; ineffective strategies; strengths of academic coaches; weaknesses of academic coaches; strengths of the program; limits of the program; gender/ethnic issues; and recommendations for future academic coaches.

Goals of the academic coach. Although the academic coaches identified their personal goals relative to what they were trying to instill among their student-athletes, most of these goals did not deviate from the five Play-It-Smart program goals. Figure 1 depicted the goals of academic coach hierarchical content analysis results.

There were 40 raw data responses in these foci. After hierarchical analysis, the goals of academic coach question responses were categorized into two higher order themes: Success/achievement goals and satisfaction/emotional well-being goals. Basically, all the academic coaches goals fell into two higher order themes. The first higher order theme goals included such raw data responses as assist student athletes achieve success beyond high school (Coach 1), going to next level of college, military, or successful employment (Coach 6), and better prepare for the next transition of their lives (Coach 4). Then, the success/achievement goals were categorized into three lower order themes including academic skill development goals, life skill development goals, and providing opportunity goals. Academic skill development goals included such raw data responses as increasing GPA, 100% graduation rate, increasing SAT scores. Life skills development goals included having future forward thinking, striving for something better, and to help themselves. The providing opportunity goals category contained raw data responses like providing an opportunity that the players never thought they had, expose them to opportunities, and provide them opportunities to interact with positive role models.

The second higher order theme was satisfaction/ emotional well-being goals. This category included such raw data responses as want these kids to be happy, feel good about themselves, want each player to develop a sense of believing in himself.

Success stories. Every coach interviewed had numerous success stories to share. In fact, on some occasions the interviewer had to stop them in order to proceed through the interview guide. Further content analysis did not seem to be appropriate for this section because of the individualistic and contextual nature of each story. Instead, efforts were made while reading those stories to identify effective strategies that seemed to work for those coaches citing them. Findings were complied and discussed in the later section (i.e., effective strategies) of this paper. For many of academic coaches, it was the success stories that allowed them to keep going against the all odds. However, they emphasized that the success was for the student athletes not the academic coaches themselves.

It was also apparent that their success stories did not stop after the season was over. Their stories went on after the players graduated. Their students were constantly contacting the academic coaches and visited their high schools after graduation. Some success stories turned out to be failures (e.g., Coach 6) and some of their failures became tremendous triumphs. For these academic coaches success was on going process rather than a definite end point.

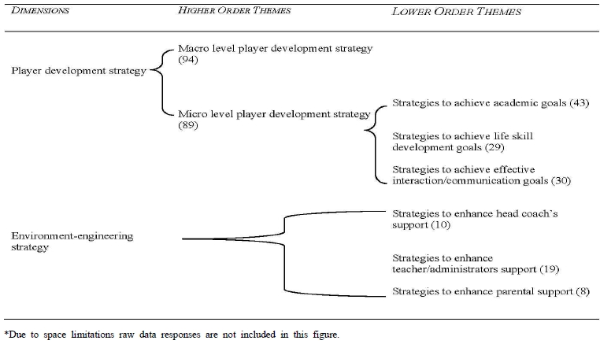

Effective strategies. Overall, a total of 238 raw date responses were identified in response to questions focusing on effective life skill coaching strategies and the previously mentioned success stories responses. These responses were then categorized into two general dimensions. The first and largest dimension was the player development strategies. The second and much smaller dimension was environment-engineering strategies.

The player development strategies category was further divided into two higher order themes: macro level player development strategies; and micro level player development strategies. Macro level player development strategies included general relational strategies such as be consistent, be patient, be real with them, have an open door policy, establish a relationship first, treat players like your own children, know when to push and when to back up, take time to get to know the players, individualize each case, be yourself, and push with support. The micro level player development strategies category was further sub divided into three lower order themes: (1) strategies that aimed to achieve players’ academic goals; (2) strategies that aimed to achieve players’ life skill development; and (3) strategies that helped increase the effectiveness of their interactions with players.

Strategies that aimed at assisting players in achieving academic goals included having junior players help 8th graders academically in the morning, setting clear goals for each class, keeping study hall interactive (i.e., allowing them to talk to each other), setting ambitious academic goals, keeping track of where players were academically (e.g., having academic progress folders for each athlete and making those folders available to the players all the time), being a micro manager in filling out college applications (e.g., making sure that the players put the correct amount of postage on their application packages), providing players a sheet to list their homework on for the day, and giving players a calendar to organize academic materials.

Strategies that were aimed at helping players achieve life skills development goals included having a monthly theme goal (e.g., self-determination for August, communication for September, and so forth), emphasizing the importance of responsibility, reminding players of the importance of the team concept (i.e., value of working together), having big brother type of program between Junior Varsity and Varsity players, having personal meetings with individual players, using past year players’ names to make players relate more, giving real life examples, using movie analogies to stress forward thinking (e.g., asking players to think about what kind of life movie that they want to be featured in), giving players many options (i.e., providing alternative options that players could feel successful), developing a sense of believing in themselves, helping players see their vision, letting players know that they could be a good student, using a trouble maker as a leader, focusing on little things (e.g., how to shake hands, how to make an eye contact), focusing on positives, helping players better understand who they are by asking questions (e.g., who are you, what do you do, and who do you what you do for), telling players the difference between saying I am sorry and I apologize.

The third micro level player development strategy theme focused on ways to improve interactions or communication with players. These strategies included making short and constant interactions, treating seniors differently (e.g., less intrusive), saying the same thing to the players over and over again, being available after their graduation, keeping the meetings short and to the point, meeting with students a half hour before the school starts and letting them vent before they start their day, using an outside school environment (e.g., community service activities) to talk about the more personal side of theirs, talking to players during practice (e.g., water break), not allowing your players to see your frustration with them, starting the initial meeting with a question like ‘tell me about yourself’, never using word, ‘should’ or ‘you have to do this’, giving all students one’s phone number, switching gears of communication mode depending on who you are talking to (i.e., students versus principal), having your first day speech ready, catching players during lunch time, intervening immediately, and using a pep talk.

Finally the second environment-engineering dimension included strategies that engineered support from: (1) head coaches (e.g., having regular meetings with the head coach); (2) from teachers and school administrators (e.g., offering volunteer work for teachers, guest lecturing for teachers); and, (3) from parents (e.g., keeping parents updated on their students progress by sending progress report). Figure 2 represented the effective positive youth development strategies hierarchical content analysis results.

Although there were different coaching styles (e.g., being sensitive or being firm) evident across the 10 academic coaches, there was one characteristic that they all shared. It was the amount of passion these individuals exhibited for their players’ development. Throughout the interviews, the high level of emotional attachment that these academic coaches had toward their players was evident. They were all highly passionate about what they have been doing. Great excitement was evident when they talked about their success stories and deep disappointment when they revisited their failures. In general, these successful academic coaches were strongly committed and dedicated to their players’ development, worked extremely hard to achieve their goals, were deeply concerned about the well-being of their players, and were closely involved with players’ personal lives. In addition, they were convinced that the program would work eventually and make a positive contribution to their players’ lives. Passion for the program and players fueled their efforts to spend countless hours working to achieve program goals.

Although these academic coaches were passionate, caring individuals, this was not all that they had. They were competent in what they were doing and had clear action plans designed to meet the players’ needs and guide them to the right paths in lives. In other words, not only did they have big hearts (i.e., passion) to work hard for the players, but they also had well developed skill sets (i.e., competencies) to determine the best ways to make those dreams come true. These academic coaches knew what their players needed to do to get where they wanted to be.

Another characteristic that academic coaches seemed to possess was resiliency. Not a single academic coach had smooth and instant success. Behind those victories (i.e., success stories), they had to fight through continuous obstacles and roadblocks. They viewed those obstacles as temporary setbacks and were able to bounce back. Previous researches (e.g., Hellison, 1993; Kallusky, 1996) showed that resiliency was a strong indicator of students’ success in inner-city environment. Interestingly, the same quality that made students successful seemed to be crucial for these academic coaches. Relative to being resilient, most coaches were able to maintain their optimistic views toward success. Maintaining a high level of optimism despite numerous obstacles appeared to require high level of resiliency.

The final characteristic of effective positive youth development specialist was, what one coach called, “people skill”. They were communicative, open, able to read the players well, knew when to push them and when to stop, and most of all they were extraordinary listeners. These characteristics helped these academic coaches work efficiently in creating positive supporting environments that increased their chances of being successful.

Positive youth development strategies can be categorized into two hierarchical levels. One is global macro level strategies and the other is specific micro level ones. Based on the interviews, a number of youth development strategies, both in macro and micro level, perceived to be effective were identified. However, it should be noted that while the coaches perceived these strategies were effective, they were not viewed as panacea for all athletes in all situations. In other words, many of these positive youth development strategies seemed to work generally well with the majority of the inner city high school players; yet that was not the case for certain students in certain situations. Therefore, those effective youth development strategies were highly sensitive to the contexts and particularities of each player. Nonetheless, it was possible to delineate the common strategies perceived as generally effective that were shared by these successful academic coaches.

The biggest global relational strategy identified by all academic coaches was being consistent. After all, it was not a specific technique or method that made them successful, rather it was their consistent presence staying with their players for an extended period of time that was important. In this sense, the biggest life skills developing strategy in this inner city high school football context was not about what academic coaches did; rather it was the fact that they were a consistent source of support for these players. Specific micro level strategies such as consistently saying the same thing over and over again to the players, being there all the time, establishing structure in their schedules, and being available after graduation were related to this general macro level strategy – being consistent. One coach described herself as “a rock”, which also touched on the same macro relational strategy of being consistent. Being consistent seemed to be particularly important for those inner city football players who did not have many consistent adult figures in their lives.

Somewhat related to the previous strategy, was the popular macro level strategy being patient. Specific strategies such as starting the program slowly (e.g., spend more time in observing during the first year and start implementing different things during the following year), listening to what the player had to say first before jumping into the solution, keeping on the players despite a series of failures, and trying to understand the stories of their young men fell into this general strategy of being patient.

A third effective life skills development macro strategy was demonstrating various ways that the players could be successful. One player might be successful in increasing SAT scores yet another could experience success in helping others during community service activities. Recognizing that fact that there were different paths and different goals for each individual helped these players feel successful as well as the academic coaches keep working despite many short-term setbacks.

All academic coaches agreed that building relationships with players was a must for them to be successful. Consequently, an extensive effort was placed on forming that relationship. Many spent countless hours with their players interacting, counseling, or just chatting. Interestingly, most academic coaches agreed that a casual form of interactions with their players were more effective than a formal counseling approach.

Finally, all coaches had strategies to engineer their environments positively. They all understood the importance of those environmental components in order to achieve their personal as well program goals. Working within the adverse inner city environment presented enormous tasks for the academic coaches. They put extra efforts into converting negative perceptions of teachers, administrators, parents, and eventually that of players to more positive ones. Specific environmental engineering strategies included sending updates to teachers and parents regarding the progress of the students, having regular meetings with head coaches, and participating in school meetings.

These findings resonate with the effective youth developing strategies discussed earlier. Comparing to Orlick and McCaffrey (1991)’s youth developing strategies, at least six out of eight categories (e.g., individualized approach, multiple approaches, be positive and hopeful, use role models, involve parents, keep it fun) in their approaches appeared to be overlapped with the findings of current investigation. Weiss (1990) also emphasized the environmental engineering strategies (e.g., coach and parent education and communication skills) in youth development. Similarly, youth development strategies from Life Development Intervention approach showed direct ties to the present findings. Specifically, Al Petitpas’ (2000) “littlefoot” approach to establishing relationship strategies which involves series of one-on-one individual interaction was restated by several academic coaches. Strategies such as understanding the problem before you fix it, pacing before you leap (i.e., matching with student-athletes progress), and having plans for setbacks were directly liked to this approach.

Interestingly, while different youth development approaches shared some similarities, strategies offered by Hellison’s Responsibility Model (Hellison, 1995) most resembles that of these academic coaches. Strategies such as focusing on strengths rather than weaknesses, being sensitive to youngster’s individuality, encouraging independence, emphasizing long-term involvement, providing a safe environment, and providing alternative options for success (Hellison, Cutforth, Kallusky, Martinek, Parker, & Stiehl, 2000; Hellison & Templin, 1997) were repeatedly mentioned by the participants of this study. It seemed that the contextual similarities between the current study and the most responsibility model implementation settings (i.e., inner-city public school) might resulted in similar strategies.

It seemed that these two approaches also shared some fundamental aspects in youth development strategies (e.g., individualized approach, focusing on the player’s development, and relationships first) but a certain aspect was emphasized more than the other depending on the contexts that the programs were implemented. For example, when working with inner-city high school football team, global strategies such as being consistent and patient were the most crucial strategies. While being consistent and being patient could certainly be desirable strategies in any setting, academic coaches felt strongly that these were more important strategies when working with players who scarcely had a positive stable adult figure in their lives. Similarly, environmental engineering strategies were perceived to be important but most of their efforts were put into turning negative circumstances and events into somewhat positive ones. It is likely that if they were working in the affluent private school system, their environmental engineering strategies would focus on utilizing all the resources that were available rather than fighting against pervasive negativity. In conclusion, those effective youth development strategies were strictly bounded to the situational context.

Based on findings from the current study, a model for effective life skills development strategies is proposed (Figure 3). The base of the triangle represents the strategies that created the environmental support system. Early on in their careers, most academic coaches realized the importance of environmental factors for their success and worked extremely hard to establish a solid and supportive environment. For example, they volunteered their time and effort for extra interactions with key school personnel (e.g., principal, athletic director, head coach, and teachers) as well as with significant others (e.g., parents). Through these positive interactions academic coaches were able to bring about mutual understanding and positive partnerships. Establishing positive and supportive relationships with key components was a foundation for future success for implementing life skills developing strategies especially, when working in a less than ideal inner city environment. These environmental engineering strategies are placed at the bottom of the triangle since these strategies seemed to provide a base for the future success (i.e., player life skills development) and help implement life skills developing strategies in the long run.

The next level of the model contains macro level relational strategies. This step ensured the development of meaningful relationship between the academic coaches and players. Strategies such as being consistent and patient are included in this level. Basically, academic coaches needed to earn the respect and trust from the players before they implemented any specific micro level life skills development strategies. Also, coaches developed a more realistic view on their players.

Finally, micro action strategies targeted a specific youth development goal. Specific strategies designed to increase GPA, graduation rates, or community service hours can be utilized. For example, in order to increase GPA, one coach recruited teachers to help improve her players’ academic skills during their study hall hours. Other coaches used a movie analogy (i.e., where’s your movie going?) to help his players set and pursue their goals. At this stage, coaches expect meaningful changes and outcomes relative to players life skills development.

It should be noted that although there is a general desirable sequence (i.e., environmental engineering strategies – macro relational strategies – micro goal specific strategies), each level operates simultaneously in the real world. In other words, academic coaches needs to ensure their environment to be supportive and positive while being consistent with their athletes. At the same time, as he or she maintains their stance firmly, each coach constantly implemented goal specific micro level strategies. In conclusion, the relationship among the three pieces is reciprocal.

Stories that these academic coaches shared demonstrated why and how they felt that they and ultimately the Play It Smart program has been successful. These coaches were passionate and caring individuals who had skills and competencies to help inner city youngsters envision their optimistic tomorrows. Moreover, the program provided these coaches with strong foundations and various tools to succeed in developing their players. Most importantly, these coaches truly bought into the program and continuously implemented various action strategies offered by the program.

The present study describes a success story of one particular program based on 10 successful individuals. Certainly, these success stories would not be exactly applicable to every context. However, this study provides general guidelines when working with high school football players within a less than ideal environment. After all, it was not complex or sophisticated techniques that made them successful; it was rather simple and small things they did everyday that made them successful.