ISSN : 1598-2939

ISSN : 1598-2939

ⓒ Korea Institute of Sport Science

Competition among golf courses in South Korea for recruiting and retaining customers has increased dramatically over the years as the number of golf courses grew. Therefore, it has become important for golf course managers to understand what attracts golfers to their golf courses. The purpose of this study was to examine the relationships among motivation, service quality, customer satisfaction, and loyalty among recreational golfers in South Korea. Total 563 recreational golfers participated in this study and responded to a self-administered survey measuring the constructs. The result showed that intrinsic motivation and extrinsic motivation were positively associated with service quality whereas amotivation was negatively related to service quality. In addition, golfers’ perceived service quality had a positive impact on golfers’ satisfaction and loyalty towards golf courses. These results suggest that golf course managers should understand the types and levels of motivation golfers have and develop strategies for enhancing service quality.

Competition among golf courses in South Korea for recruiting and retaining customers has increased dramatically over the years as the number of golf courses grew. Therefore, it has become important for golf course managers to understand what attracts golfers to their golf courses. The purpose of this study was to examine the relationships among motivation, service quality, customer satisfaction, and loyalty among recreational golfers in South Korea. Total 563 recreational golfers participated in this study and responded to a self-administered survey measuring the constructs. The result showed that intrinsic motivation and extrinsic motivation were positively associated with service quality whereas amotivation was negatively related to service quality. In addition, golfers’ perceived service quality had a positive impact on golfers’ satisfaction and loyalty towards golf courses. These results suggest that golf course managers should understand the types and levels of motivation golfers have and develop strategies for enhancing service quality.

Golf is one of the popularrecreational activities in South Korea. As it gains its popularity, the number of golf courses and the participants has increased steadily over the years. According to Korea Golf Course Business Association (2013), the number of golf courses in South Korea increased more than 100% over 10years of the periodfrom 2002 (117) to 2012 (248). Meanwhile, the number of people playing at these golf courses has also increased from 11,169,522 to 18,250,345 during the same period. Although both numbers have been increasing, the trend is that the number of golf courses is outgrowing the number of customers. This indicatesthat the competition among the golf courses for the customers has been increasing dramatically, and it has become critical for the golf course managers to identify important factors that impact customer satisfaction and loyalty so that they can recruit and retain the customers and survive in a saturated market environment.

Regarding a major factor that influences customers’ intention to return to service providers, service quality has recently received much attention among researchers. A great number of studies have focused on identifying different dimensions of service quality in various sportsettings, such as spectating sport (Yoshida & James, 2011) and participant sport (Ko & Pastore, 2004). In addition, the related behavioral intentions and outcomes have been widely studiedin the marketing literature. However, while there are numerous studies that have examined consequences of service quality (e.g., customer satisfaction and loyalty), not many studies have looked at antecedents of service quality. This limited literature on service quality antecedentswas mainly conducted in an organizational behavior context. These studies investigated perceived organizational support, leader-memberexchange, and psychological empowerment as predictors for quality of service employees provide to customers (Jaiswal & Dhar, 2016).

Someliterature in a consumer behavior context recognized motivation as an antecedent of customers’ perceived service quality (Chong & Ahmed, 2015; McCabe, Rosenbaum, & Yurchisin, 2007). A few sport management scholars also researched the link between motivation and service quality (Ko & Pastore, 2005). However, the studies have been greatly limitedto a spectating sportsetting (Caro & Garcia, 2007). Despite the past literature that confirmed a strong relationship between motivation and service quality, there is a lack of information in the sportmanagement literature regarding how individuals’ motivation to participate in the sportactivity influences their level of perceived service quality. Researchers have argued that an individual’s level of perceived quality is greatly influenced by consumer’s motivefor engaging in a specific consumption behavior (Ko & Pastore, 2005; McCabe et al., 2007).However, only a few sportmanagement literature has examined motivation as an antecedent of perceived service quality. Giventhe size of the participant sportmarket and the importance of service quality in retaining customers, such a relationship should be studied in a sportsetting, particularly in a participant sportsetting.

Althoughseveral studies investigated the link betweenservice quality, satisfaction,and behavioral outcomes, the focus of many service quality studies havebeen limitedto the relationship between service quality and satisfaction (Baker & Crompton, 2000; Greenwell, Fink, & Pastore, 2002). For example, Greenwell et al. (2002) argued that physical facility is an important element that is frequently evaluated by consumers when they judge service quality. However, the authors only focused on how it is related to customer satisfaction and failed to examine how the quality of physical facility impacts re-patronage of the consumers. From the manager’s perspective, the most important outcome of service quality is loyalty as it is directly associatedwith the revenue of the sportorganizations (Kyle, Theodorakis, Karageorgiou, & Lafazani, 2010).For this reason, loyalty should be studiedas an important behavioral outcome of service quality.

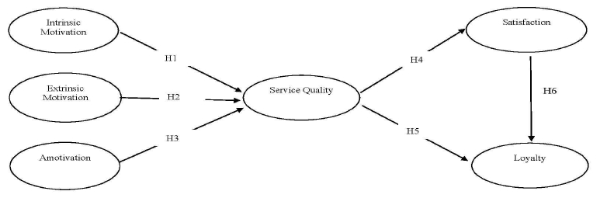

Therefore, the purpose of this study is two folds: to examine the relationship between three forms of motivation for golf participation and service quality and to further investigate the relationships among service quality, customer satisfaction, and loyalty.

Retaining existing customers has always been an ongoing challenge to many service organizations due to its direct connection with organizational effectiveness. In fact, researchers and practitioners have been looking for factors that influence customer satisfaction and loyalty as they lead to revisitingand/orrepurchase of the service or product. One of the factors frequently discussed in relation tocustomer satisfaction and loyalty is service quality. Service quality is defined as “the consumer’s overall impression of the relative inferiority/superiority of the organization and its services” (Bitner & Hubbert, 1994, p.77). According to Parasuraman, Zeithaml, and Berry (1985), service quality is determined by “a comparison of consumer expectations with actual service performance” (p.42). When customers evaluate the service quality, they evaluate multiple aspects (Chelladurai & Chang, 2000). Langeard, Bateson, Lovelock, and Eiglier (1981) suggested that there are three components of the service customers evaluate. These include the inanimate environment, service personnel, and a bundle of servicebenefits. Up to recent years, many sport management researchers have employed these three components in developing dimensions of service quality in a given context as each industry faces different service environment. For example, reflecting these three componentsand the golf environment in South Korea, Yeo, Kim, Lee, and Cho (2010) suggested that there are seven attributes that composethe service quality in the golf industry in South Korea. These include the convenience of website reservation system, accessibility, course difficulty, cost, physical environment, caddy competency, and employee service. In addition, Ko and Pastore (2004) claimed that there are four dimensions (i.e., program quality, interaction quality, outcome quality, and physical environment) for service quality in a recreational sportsetting. Regarding a spectating sportsetting, Yoshida and James’ (2011) study on Japanese and American spectators found that there were three dimensions, which include aesthetic, technical, and functional qualities, of service quality.

As such, service quality has also been measured by various scales to fit into different service industries in the past literature. Many scholars used SERVQUAL scale developed by Parasuraman et al. (1985) or modified version of SERVQUAL (Howat, Absher, Crilley, & Milne, 1996; McDonald, Sutton, & Milne, 1995; Yeo et al., 2010). On the other hand, others developed their ownscales to fit into a specific sport or settings they investigated (Chelladurai & Chang, 2000; Ko & Pastore, 2005; Yeo et al., 2010). For instance, Yeo et al. (2010) modified SERVQUAL to measures golfers’ perception of service quality on golf courses in South Korea whereas Ko and Pastore (2007) developed The Scale of Service Quality in Recreational Sports (SSQRS) that measures participants’ perceptions of service quality in recreational sportprograms.

Self-determination theory (Deci & Ryan, 2000) indicates that there are three types of motivation: intrinsic motivation, extrinsic motivation, and amotivation. Individuals who are intrinsically motivated engage in certain behaviors because of the pleasure the activities bring to them. On the other hand, extrinsically motivated individuals partake in a behavior because of rewards or external variables, such as social constraints (Deci & Ryan, 2000). While intrinsic motivation and extrinsic motivation spectrum could be from high to low, amotivationrefers to no or low level of motivation to perform given tasks. In other words, people with amotivationtypically don’t have any particular reasons to be engaged in a behavior meaning neither intrinsic nor extrinsic motivation is present (O’Connor & Vallerand, 1989). Previous studies suggest that high level of motivation, either intrinsically or extrinsically, elicits positive performance outcomes as the reasons for participation or behavior is associated with certain benefits they desire (Vlachopoulous, Karageorghis, & Terry, 2000). However, amotivationis negatively related to desired outcomes because motivation itself is lacking and individuals don’t see any benefits of participating in certain activities (Vlachopoulous et al., 2000).

In this sense, it can be speculatedthat different types of motivation are linkedto perceived service quality. According to McCabe et al. (2007), consumers’ perception of service quality is influencedby their motivation in a specific consumption environment. In other words, perceived service quality is a function of consumers’ motive for engaging in the consumption behavior. Similarly, Ko and Pastore (2004) emphasized that individuals’ motives for sportparticipation determine the participants’ level of service quality. The notion is that the motivations for participation influenceexpectations formed before participation and this affectoverall experience with the service received (Chong & Ahmed, 2015).

Although there is a lack of studies on the relationship between individuals’ motivation to participate in sport and service quality in the sportmanagement literature, the significant relationship has been foundin other contexts. In fact, consistent findings in the previous literature suggest that individuals’ level of motivation is highly associated with perceived service quality (Chong & Ahmed, 2007; McCabe et al., 2007). For example, in the study of university service quality, Chong and Ahmed (2007) found that students’ perceived university service quality greatly depended on their motivation for participating in higher education. Similarly, McCabe at al. (2997) discovered that shoppers’ perceived service quality on a retail organization was predicted by shopping motivations.

Following self-determination theory (Deci & Ryan, 1985) and the previous literature, it can be assumedthat the participants’ reasons for playing golf have an impact on the quality of service the consumers’ perceive towards golf courses. Therefore, the following hypotheses are proposed.

One of the areas service organizations focus on in order tosurvive in a competitive market environment is achieving customers’ satisfaction. In fact, satisfaction, defined as “a judgment that a product or service feature, or the product or service itself, provides a pleasurable level of consumption-related fulfillment” (Oliver, 1997, p.13), is vital in retaining and recruiting customers. Therefore, it is directly associatedwith organizational effectiveness, which determines the survival of the organization.

The marketing literature consistently reports that the constructs of service quality and satisfaction are closely related (Papadimitriou, 2013). In fact, previous studies suggest that customer’s perceived service quality is significantly associatedwith customer satisfaction, which in turn leads to the customers’ revisit intention (Baker & Crompton, 2000; Greenwell et al., 2002). In the sport management literature, there are generally three types of consumers scholars have focused on examining the relationship between service quality and satisfaction: spectators (Biscaia, Correia, Yoshida, Rosado, & Maroco, 2013; Koo & Hardin, 2009), participants (Shonk, Carr, &Michele, 2012; Yu et al., 2014), and sport service users (Kim, Kim, Lee, Judge, & Huang, 2013; Kim, Kim, Park, Yoo & Kwon, 2014; Nuviala, Garo-Cruces, Perez-Turpin & Nuviala, 2012).Those studies all support that customers’ perceived service quality is strongly and positively associatedwith satisfaction. For example, examining a moderating role of identification in the relationship between service quality and satisfaction, Shonk et al. (2012) demonstrated that service quality attributes (i.e., program quality, interaction quality, outcome quality, and physical environment quality) were highly associated with university campus recreation participants’ satisfaction with recreational sport service.Yu et al. (2014) also discovered that among older (aged 60 years and over) fitness club members, fitness center’s service quality, such as staff, program, locker room, physical facility, workout facility, was directly related to their level of satisfaction with the fitness center. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed.

When customers are satisfied with service quality, they are more likely to engage in positive behaviors, such as repurchase, word of mouth and loyalty (Zeithaml, Berry, & Parasuraman, 1996). In particular, a construct that is closely related to satisfaction and impacts overall success of the organization is loyalty because loyalty consumers have further leadsto other behavioral consequences (Kyle et al., 2010). Loyalty, defined as “commitment toward preferred products or services” (Liat, Mansori, & Huei, 2014, p. 318), motivates customers to engage in repetitive purchase behaviors. Therefore, loyalty has a greatinfluence on the overall profitability of an organization. Generally, researchersagree that satisfaction and loyalty are intercorrelated. In fact, ample evidence suggests that high quality of service yields a higher level of customer satisfaction and satisfaction strengthens loyalty (Kyle et al., 2010; Petrick & Backman, 2002; Yuan & Jang, 2008). Such a relationship has been well demonstrated in various job settings, such as hotels (Liat et al., 2014), banks (Khan & Fasih, 2014), rail services (Chou, Lu, & Chang, 2014) and casino (Shi, Prentice, & He, 2014). Sportmanagement literature also provides empirical evidence for the satisfaction and loyalty link. For example, in the context of ski resorts, Kyle et al. (2010) found that service quality, which consists of interaction quality, facility quality, and outcome quality, was positively associated with satisfaction, and satisfactionled to behavioral loyalty through commitment. Similar results were also foundin Cronin, Brady, and Hult’s (2000) study that cross examined six service industries: spectator sport, participation sport, entertainment, health care, long distance carriers, and fast food. In the study of sportspectators and participants, it was revealedthat customers’ perceived service quality was significantly and positively associatedwith satisfaction and satisfaction was strongly related to behavioral intentions. Thus, the following hypothesis is proposed.

Although many researchers generallyagree that satisfaction precedes loyalty, recently some scholars have suggested a direct link between service quality and loyalty (Shi et al., 2014; Shoemaker & Lewis, 1999). According to Kale (2005), satisfaction doesn’t necessarily translate into loyalty because satisfaction is an unstable condition of loyalty. In fact, Kale (2005) found that only 30-40% of satisfied customers returned to purchase in a car manufacturer setting. This notion can be well appliedto a recreational golf environment. Frequently, satisfaction with sportparticipation experience depends on an individual’s performance outcome. That is individuals’ satisfaction level may be simply from the desired performance outcome, and this has an influence on the golf course they prefer to visit (Shi et al., 2014). Therefore, satisfaction may not be a precondition of loyalty in certain cases, and the direct link between service quality and loyaltycould be found. In this sense, the following hypothesis is formulated.

The proposed model for this study is presentedin Figure 1.

To test the conceptual model, the data were collectedfrom recreational golfers at various golf courses in South Korea using a convenience sampling technique. Total 563 responses were deemed usable for analysis after eliminating unusable data. The response rate couldn’t be calculatedas the current study used a convenience sampling technique and the questionnaire was available to any willing participants who played golf at the selected golf courses.Of the participants, 504 (89.5%) were male, and 59 (10.5%) were female. The majority of the participants was in the age range of 40-49 (285, 50.6%) followed by the age range of 30-39 (153, 27.2%), 50-59 (89, 15.8%), 60-69 (18, 3.2%), and 20-29 (18, 3.2%).Total 227 (40.3%) respondents indicated that their monthly income was over $3,000 and less than $6,000 while the monthly income of 199 (35.3%) respondents ranged between $6,000 and $10, 000. Also, 84(14.9%) respondents indicated that their monthly income was between $10,000 and $19,999 followed by 47 (8.3%) respondents’ monthly income ranging $20,000 or higher, and 6 (1.1%) respondents’ monthly income being less than $3,000.

The self-administered questionnaire included five sections: (1) respondent characteristics (i.e., demographic information), (2) three motivations (i.e., intrinsic motivation, extrinsic motivation, and amotivation), (3) seven service quality constructs (i.e., convenience of website reservation system, accessibility, course difficulty, cost, physical environment, caddy competency, and employee service), (4) customer satisfaction, and (5) loyalty.Questions regarding respondent characteristics included items such as gender, age, and monthly income. Three types of motivation were measuredby a 12-item scale modified from Chung’s (1997) scale to fit into a recreational golf setting. Service quality was measured by Yeo et al.’s (2010) scale, which was specifically developedfor golf course environment in South Korea. Customer satisfaction was measured using a 3-item scale developed by Oliver (1993). Finally, Loyalty was measuredby four items modified from Yoon and Uysal’s (2005) scale. Participants were asked to rate each item on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). All items of measurements are includedin Table 1.

| Factor (α) | Items | β | α | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intrinsic Motivation | I play golf because I find it interesting. | 0.85 | .88 | .88 | .66 |

| I play golf because it is enjoyable. | 0.87 | ||||

| I play golf because it is fun. | 0.78 | ||||

| I play golf because I feel good when I play golf. | 0.73 | ||||

| Extrinsic Motivation | I play golf because I have to. | 0.70 | .76 | .81 | .52 |

| Iplay golf because it is one of the things I have to | 0.76 | ||||

| I play golf because I have no other choice. | 0.67 | ||||

| I play golf because I feel I need to | 0.74 | ||||

| Amotivation | I understand the benefits of playing golf, but none of them applies to me. | 0.78 | .82 | .82 | .53 |

| I play golfbut I don’t know if it is worth it. | 0.76 | ||||

| I play golf but I don’t know how it benefits me. | 0.63 | ||||

| I play golf but I don’t know if I should continue it. | 0.73 | ||||

| Website Reservation System | It is easy to use the golf course website. | 0.90 | .84 | .84 | .73 |

| The golf course online reservationsystem is convenient. | 0.80 | ||||

| Accessibility | The golf course is easily accessible. | 0.91 | .86 | .76 | .87 |

| It is easy to drive to the golf course. | 0.83 | ||||

| Physical Environment | The exterior of the club house is well maintained. | 0.92 | .83 | .85 | .65 |

| The atmosphere inside of club house is good. | 0.7 | ||||

| The view of golf course from the club house is good. | 0.79 | ||||

| Course Difficulty | The level of difficulty at the golf course is good. | 0.75 | .76 | .82 | .53 |

| The level of difficulty at the fairway is good. | 0.62 | ||||

| Grass quality of the golf course is good. | 0.62 | ||||

| The golf course was challengeable. | 0.89 | ||||

| EmployeeService | Front office employees are very friendly. | 0.83 | .92 | .92 | .69 |

| Golf course restaurant employees are very friendly. | 0.87 | ||||

| Rest area employees are very friendly. | 0.81 | ||||

| On siteemployees are very friendly. | 0.81 | ||||

| Parking lot employees are very friendly. | 0.82 | ||||

| CaddyCompetency | The caddy isvery friendly. | 0.81 | .88 | .87 | .72 |

| The caddy provides excellent service on the course. | 0.89 | ||||

| The caddy providesprofessional advice on my play. | 0.85 | ||||

| Cost | The price at golf course restaurant was reasonable. | 0.74 | .72 | .73 | .58 |

| The green fee was reasonable. | 0.78 | ||||

| Satisfaction | I am satisfied with my experience at thisgolf course. | 0.84 | .90 | .91 | .75 |

| This golf course was a good choice for me. | 0.92 | ||||

| I am glad that I chose this golf course. | 0.84 | ||||

| Loyalty | I will revisit thisgolf course. | 0.88 | .88 | .89 | .68 |

| I will tell people about the positive experience I had at thisgolf course. | 0.88 | ||||

| I will recommend thisgolf course to others. | 0.77 | ||||

| I will consider this golf course as my first choice next time. | 0.75 |

The Statistical Package for the Social Science (SPSS) 22.0and AMOS 22.0 were utilized to examine the data and psychometrics of the scales.Descriptive statistics (e.g., demographic information) and internal consistency reliability (e.g., Cronbach’s alpha) wereexamined by SPSS.To evaluate the conceptual model, the study followed a two-step procedure suggested by Anderson and Gerbing (1988). The first step was to validate the measurement model usingConfirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) (e.g., reliability, convergent validity, discriminant validity). The second stepappliedStructural Equation Modeling (SEM) to examine the proposed relationships between each construct.

The measurement model, which includes 12 factors and 40 items, was estimated to assess the fit, discriminant validity, and internal consistency among the model’s construct measures using Second-Order Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA), (Anderson & Gerbing, 1988). To assess the goodness-of-fit and the parsimony of the model, theRoot Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), CFI, IFI, and TLI were examined(Anderson & Gerbing, 1988). The results revealed that the measurement model fit the data well (χ2/df =1529.12/674 = 2.27, RMSEA (90% CI) = .048 (.044-.051), CFI = .93, IFI = .93, TLI =.92).In addition, the second order factor of service quality was well represented by the first order factors of website reservation system (β= .58, p<.01), accessibility (β= .48, p<.01), course difficulty (β= .65, p<.01), cost (β= .41, p<.01), physical environment (β= .63, p<.01), caddy competency (β= .81, p<.01), and employee service (β= .85, p<.01). All Cronbach’s alpha values of the scales ranged from .72 to .92, which are above the suggested minimum threshold of .70 (Hair, Anderson, Tatham, & Black, 1998). Construct reliability of measures for each of the latent variables exceeded the recommended standard of .70 (Nunnally, 1978). Convergent validity was measured to test both the significance of the factor loadings and the Average Variances Extracted (AVE). All loadings were statistically significant (p< .01) and all of the AVEs were above the suggested minimum threshold of .50 (Fornell & Larcker, 1981), thus providing strong evidence of convergent validity (see Table 1).

To test discriminant validity, a comparison was madebetween the AVEsof a construct with the shared variances between the construct and all other constructs in the model (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). The results provided that all AVEs of a construct exceeded the shared variances between the construct and all other constructs in the model (Fornell & Larcker, 1981) (see Table 2).

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Intrinsic Motivation | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| 2. Extrinsic Motivation | .05 | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| 3. Amotivation | -.37** | .26** | 1.00 | |||||||||

| 4. Reservation System | .25** | .11** | -.17** | 1.00 | ||||||||

| 5. Accessibility | .20** | .01 | -.20** | .47** | 1.00 | |||||||

| 6. Physical Environment | .19** | .09* | -.04 | .36** | .25** | 1.00 | ||||||

| 7. Course Difficulty | .17** | .13** | -.02 | .25** | .17** | .41** | 1.00 | |||||

| 8. EmployeeService | .29** | .05 | -.16** | .38** | .31** | .47** | .43** | 1.00 | . | |||

| 9. Caddy Competency | .27** | .03 | -.20** | .37** | .35** | .39** | .40** | .71** | 1.00 | |||

| 10. Cost | -.02 | .21** | -.16** | .15** | .02 | .21** | .32** | .28** | .24** | 1.00 | ||

| 11. Satisfaction | .36** | .08 | -.17** | .38** | .32** | .46** | .39** | .50** | .50** | .25** | 1.00 | |

| 12. Loyalty | .27** | .06 | -.16** | .37** | .31** | .49** | .41** | .51** | .49** | .28** | .68** | 1.00 |

Following the confirmation of the measurement model, the conceptual model was evaluatedby SEM including the test of path estimates (see Figure 2). The results indicated that the model provided a good fit to the data with several different indices (χ2/df =1795.6/724 = 2.48, RMSEA (90% CI) = .051 (.048-.054), CFI = .92, IFI = .92, TLI =.91), and allpaths between constructs were significant (p < .05). Hypotheses 1, 2, and 3 investigated the relationships among the three key antecedents on service quality. The results supported all of the hypotheses: 1(intrinsicmotivationàservice quality; β= .33, p<.01), 2 (extrinsic motivation àservice quality; β= .15, p<.01), and 3(amotivationàservice quality; β= -.12, p<.05). All relationships were statistically significant. Hypotheses 4, 5, and 6were associatedwith consequences of service quality. The results revealed that service quality significantly affects satisfaction (H4) (β= .71, p<.01) and loyalty (H6) (β= .37, p<.01). In addition, as expected, the impact of satisfaction on loyalty (H5) (β= .49, p<.01) were significantly positive.

This study investigated antecedents and consequences of service quality in the South Korean golf course industry. Motivation was includedas a predictor for service quality, and satisfaction and loyalty were examinedas consequences of service quality. The results of the study indicate that all three types of motivation had a significant impact on golfers’ perceived service quality towards the golf course. Specifically, intrinsic motivation had the most significant impact followed by extrinsic motivation and amotivation. In addition, as expected, service quality had a significant impact on satisfaction and loyalty, and loyalty was also strongly influenced by satisfaction. All the findings were in agreement with the previous literature.

The most significant finding of the study lies in the relationships between three types of motivation and service quality. Based on self-determination theory (Deci & Ryan, 1985), it seems logical that intrinsic motivation has the strongest relationship with service quality whereas amotivationhas the weakest relationship. In the self-determination continuum, intrinsic motivation is consideredas the highest self-determining form,and amotivationis consideredas the lowest self-determining form (Deci & Ryan, 2000). Previous studies have shown that self- determination influences individuals’ evaluation of service quality (Chong & Ahmed, 2015; McCabe et al., 2007). The notion is that individuals with high self-determination have a more optimistic view in their service quality perception compared to individuals with low self-determination (Chong & Ahmed, 2015). Furthermore, self-determined individuals are more likely to interact actively with service providers, which may influence their perception of service quality (McCabe et al., 2007).

Another point noteworthy in this study is a direct influence of service quality on loyalty. Up to date, the majority of literature tested the links among service quality, satisfaction, and loyalty (Kyle et al., 2010; Petrick; Backman, 2002; Shi et al., 2014). The common theory was that satisfaction is a precondition of loyalty. However, the current study found that the direct path between service quality and loyalty exists. This finding is consistent with Kales’s (2005) and Shi et al.’s (2014) claim that satisfaction doesn’t always precede loyalty. In a participant sportsetting, this may be truer as participants’ satisfaction level greatly depend on their performance outcome. Therefore, it is possible that although golfers’ perceive service quality of a certain golf course is very high and as a result, they develop loyalty and revisit the golf course over time, theymay not always be satisfied with their experience depending on their performance level.

The current study contributes to the body of knowledge within services marketing, sportmanagement,and consumer behavior literature.The theoretical implication involves the influence of motivation on customers’ perceived service quality. In particular, to the authors’ knowledge, there have not been any studies that linked individual’s level of motivation to service quality in a participant sport setting in the sportmanagement literature. Therefore, this study serves as a milestone for such a relationship. From a practical standpoint, this study enlightens golf course managers on the importance of service quality in retaining customers. According to Miller (2000), knowing customers’ needs and levels of satisfaction are the key torecruiting new customers and retaining existing customers. By understanding connections among service quality, satisfaction, and loyalty, golf course managers will be able to develop strategies for enhancing golfers’ experience. In addition, the results of this study indicate that employee service and caddy competency are the two major factors that determine customers’ perceived service quality. This is an important piece of information to golf course managers because employee service and caddy competency can be easily controlled by managers through providing trainings. Therefore, this study guides golf course managers in the areas they can improve to retain and recruit their customers. In addition, golf course managers will be able to formulate different service strategies based on the types and levels of motivation golfers have.

There are several limitations in this study. First of all, the golf courses included in this study are both public and private courses. However, the types of service provided in public versesprivate golf courses and the demographics of customers they attract may be very different (Sul & Sul, 2008). In other words, public golf course customers and private golf course customers may have different expectations, and this may impact the overall relationships included in this study. Therefore, future research should replicate the current study in two different settings (i.e., public and private golf courses) and compare how the relationships among the constructs vary. Secondly, this study used service quality as a second-orderlatent variable because previous studies confirmed that customers tend to aggregate their evaluations on different attributes of service quality to assess overall service quality (Brady & Cronin, 2001). Yet, eachattribute of service quality may influence satisfaction and loyalty on different strengths (Koo & Hardin, 2009). Therefore, the impact of each service quality attribute should be investigatedseparately. Lastly, the current study is limited to the golf industry in South Korea. Future studies should also be conducted at a cross-cultural level to see if the model fits in different sociocultural settings. In addition, antecedents and consequences of service quality in other participant sportsettings should be consideredin future research.