Emotional Dissonance, Perceived Organizational Support, Job Satisfaction, and Turnover Intention among Physical Education Professors in China

International Journal of Applied Sports Sciences, Vol.36, No.1, pp.91-103, 30 June 2024

https://doi.org/10.24985/ijass.2024.36.1.91

© Korea Institute of Sport Science

초록

The purpose of this study was to examine the relationships among emotional dissonance, perceived organizational support, job satisfaction, and turnover intention among physical education professors in China. The population for this study consisted of physical education professors in L province, China. Convenience sampling was utilized, and a total of 192 participants participated the study. An online survey system, Tencent Questionnaire, was employed to administer the survey. Data analysis was conducted using SPSS 27.0 and AMOS 27.0, and structural equation model was employed to examine the relationships among the variables. According to the results, first, perceived organizational support has no significant effect on emotional dissonance. Second, perceived organizational support is positively related to job satisfaction. Third, perceived organizational support has no significant effect on turnover intention. Fourth, emotional dissonance is negatively related to job satisfaction. Fifth, job satisfaction has no significant effect on turnover intention. Sixth, emotional dissonance is positively related to turnover intention. Moreover, perceived organizational support was a significant predictor of job satisfaction. Additionally, emotional dissonance demonstrated a negative association with job satisfaction and a positive association with turnover intention. This is the first study to highlight the importance of emotional states and contextual factors on well-being and job-related attitudes in the physical education context.

Abstract

The purpose of this study was to examine the relationships among emotional dissonance, perceived organizational support, job satisfaction, and turnover intention among physical education professors in China. The population for this study consisted of physical education professors in L province, China. Convenience sampling was utilized, and a total of 192 participants participated the study. An online survey system, Tencent Questionnaire, was employed to administer the survey. Data analysis was conducted using SPSS 27.0 and AMOS 27.0, and structural equation model was employed to examine the relationships among the variables. According to the results, first, perceived organizational support has no significant effect on emotional dissonance. Second, perceived organizational support is positively related to job satisfaction. Third, perceived organizational support has no significant effect on turnover intention. Fourth, emotional dissonance is negatively related to job satisfaction. Fifth, job satisfaction has no significant effect on turnover intention. Sixth, emotional dissonance is positively related to turnover intention. Moreover, perceived organizational support was a significant predictor of job satisfaction. Additionally, emotional dissonance demonstrated a negative association with job satisfaction and a positive association with turnover intention. This is the first study to highlight the importance of emotional states and contextual factors on well-being and job-related attitudes in the physical education context.

Introduction

Emotions have become a prominent focus within the organizational management and psychology field in the past few decades due to their significant influence on work-related attitudes and behaviors (Ashkanasy & Humphrey, 2011). Although a considerable number of studies have focused on consumer outcomes, a growing body of research has begun to examine the role of emotions in the physical education context (Lee, 2019).

The emotional burden physical education teachers experience can be ascribed to their distinct working context (Koustelios & Tsigilis, 2005; Tsigilis et al., 2011). Specifically, physical education teachers often experience a sense of marginalization and isolation (Schutz & Zembylas, 2009), partly due to the tendency of some educational leaders or stakeholders to undervalue physical education in comparison to other subjects. Additionally, the role of physical education professors in Chinese universities is multifaceted. They not only are responsible for teaching classes to students but also take responsibility for various additional roles, including sports coaches, event coordinators, advisors to student-athletes, and officials in sporting events (Liston et al., 2006).

Moreover, Chinese physical education professors teach a variety of theoretical subjects, such as sport management, sports marketing, sports sociology, and sports physiology, as well as a number of practical subjects (Lin & Shin, 2021). Their teaching is not limited to students specializing in physical education; they also instruct freshmen and sophomores from other faculties. This broad teaching scope reflects the significant workload of Chinese physical education professors. Their unique work environment causes Chinese physical education professors to face greater emotional demands than other educators.

Additionally, it is important to consider the unique context within which Chinese physical education professors operate. China is a country with a predominantly collectivist culture, wherein the group’s interests take precedence over those of the individual. This collectivist orientation may serve to alleviate some of the adverse effects associated with engaging in emotional labor. Within this framework, physical education professors often find themselves compelled to suppress their true emotions in order to align with organizational objectives, potentially resulting in emotional dissonance.

Morris and Feldman (1996) described emotional dissonance, as a dimension of emotional labor. Hochschild (1983) coined the term emotional labor to describe employees’ efforts to manifest appropriate emotions to align with their professional roles during interactions with customers in order to fulfill organizational goals. Later, Morris and Feldman (1996) defined various dimensions of emotional labor, including emotional dissonance, which occurs when employees show the required emotions to align with organizational norms instead of their true feelings.

Prior studies have investigated outcomes associated with emotional dissonance, including negative effects on job satisfaction and turnover intention (Alrawadieh et al., 2020; Ozkan et al., 2020). Job satisfaction is defined as the extent to which employees feel content and valued in their work (Ortan et al., 2021). According to Alrawadieh et al. (2020), emotional dissonance has a negative effect on job satisfaction because it creates a conflict between an employee’s authentic feelings and the emotions they are required to display, leading to stress and reduced job fulfilment.

Emotional dissonance is also positively associated with turnover intention, referring to an employee’s likelihood of leaving their current job. According to Lewis (2022), this relationship is explained by the fact that the strain of maintaining a facade of organization-required emotions can lead to job dissatisfaction and a consequent desire to seek employment elsewhere. This understanding of the implications of emotional dissonance has led researchers to explore its antecedents.

A number of studies focus on individual attributes associated with emotional dissonance (e.g., emotional intelligence) but neglect contextual factors that may help individuals to diminish emotional dissonance (Duke et al., 2009) According to Kumar Mishra (2014), perceived organizational support, referring to employees’ perception of the extent to which their organizations value and care about their contribution to the organization and their well-being, is one of the most important contextual factors that can influence emotional dissonance.

With this background, the purpose of this study is to consider the concept of emotional dissonance and explore the relationships among perceived organizational support, emotional dissonance, job satisfaction, and turnover intention. It contributes to the existing literature by being the first study to investigate these relationships simultaneously within the Chinese sports teaching context.

Theoretical Background and Hypotheses Development

Emotional dissonance: Emotional labor refers to employees’ intentional regulation of emotions during interactions with customers to achieve organizational objectives and personal financial goals (Grandey, 2000). This behavioral regulation is determined by certain organizational norms, which specify the appropriate emotional responses while concurrently advocating for the suppression of authentic emotional reactions, with the aim of ensuring optimal role performance. Morris and Feldman (1996) provide a detailed explanation of emotional labor, which they define as an individual’s conscious effort to manage and control their emotions to match the expected norms during interactions with others. An important aspect of emotional labor they identify is emotional dissonance.

Emotional dissonance is the conflict that arises when there is a gap between the emotions an individual displays and how they truly feel (Zapf, 2002). This concept is derived from Hochschild’s (1983) influential work describing emotional dissonance as a direct result of emotional labor, which occurs when an individual is required to express or suppress certain emotions during work-related interactions. When the emotions that an individual is expected to display align with their true feelings, emotional dissonance is minimal. However, if there is a mismatch between the two, emotional dissonance increases (Grandey, 2000).

Perceived organizational support: Perceived organizational support, as defined by Eisenberger et al. (1986), is a central subject in psychology and human resource management, particularly in the context of changing economic situations and organizational dynamics (Mickiewicz et al., 2005). Perceived organizational support is the employee’s perception of the extent to which their employer acknowledges their contributions and considers their welfare. It encompasses the employee’s sense of the organization’s valuation of their inputs, commitment to their well-being, and desire to preserve a positive employment relationship.

This study posits that the perception of organizational support among physical education professors is related to advantageous results. In contrast, the lack of perceived organizational support is related to negative outcomes. Existing literature indicates that employees with heightened perceptions of perceived organizational support demonstrate positive occupational attitudes, such as an increase in job satisfaction. Conversely, individuals with a lack of perceptions of perceived organizational support may exhibit behaviors such as surface acting and express intentions to depart from the organization, potentially originating from sentiments of organizational indebtedness. (Eisenberger & Stinglhamber, 2011).

The research conducted by Richards et al. (2019) also found that perceived organizational support had a negative relationship with surface acting and a positive relationship with job satisfaction. Importantly, surface acting, which is the act of displaying emotions that are not genuinely felt, can result in emotional dissonance. Similarly, Choi and Chiu (2017) found that perceived organizational support had a negative relationship with turnover intention and a positive relationship with job satisfaction. These observations also align with research conducted by Du Plessis (2010) and Treglown et al. (2018). In light of these preceding studies, and given that surface acting leads to emotional dissonance, this research posits that:

-

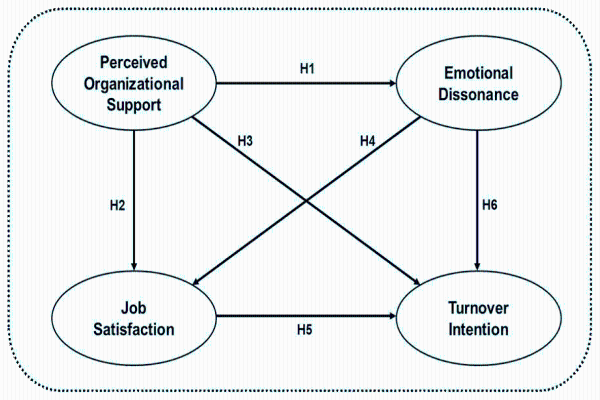

H1: Perceived organizational support will be negatively related to emotional dissonance.

-

H2: Perceived organizational support will be positively related to job satisfaction.

-

H3: Perceived organizational support will be negatively related to turnover intention.

Job satisfaction: Job satisfaction is characterized by employees’ positive evaluations and overall contentment concerning various aspects of their jobs (Chang & Edwards, 2015; De Nobile & McCormick, 2008). Several studies have explored the relationship between emotional labor and job satisfaction. Current literature consistently posits that surface acting negatively impacts job satisfaction (Côté & Morgan, 2002; Zhang & Zhu, 2008). Engaging in surface acting has psychological implications, including emotional dissonance and feelings of inauthenticity, which can lead to self-alienation and a general negative perception of one’s job. This outcome can be mitigated by reducing the disparity between genuine and expressed emotions, thereby decreasing emotional dissonance. Regarding turnover intention, a significant body of research consistently indicates an inverse relationship between job satisfaction and turnover intention (Alam & Asim, 2019; Ali, 2008). For example, a study by Cunningham and Sagas (2004) emphasized the negative impact of job satisfaction on turnover intentions, specifically among collegiate coaches. Given these previous findings, and considering that surface acting leads to emotional dissonance, the current research proposes the following hypotheses:

-

H4: Emotional dissonance will be negatively related to job satisfaction.

-

H5: Job satisfaction will be negatively related to turnover intention.

Turnover intention: Turnover intention is conceptualized as an individual’s conscious inclination or determination to terminate their existing employment relationship and voluntarily leave their current job or institution (Tett & Meyer, 1993). Numerous prior studies have examined the relationships between various emotional labor strategies and turnover intention. For instance, Goodwin et al. (2011) identified a direct relationship between surface acting and turnover intention. Consistent with prevailing literature, emotional dissonance, which indicates the incongruity between genuine emotions and those expressed, has consistently been identified as a critical determinant of the intent to leave (Grandey, 2000). Therefore, surface acting, which gives rise to emotional dissonance, might induce discomfort among physical education professors, thereby influencing their inclination to exit the profession (Goodwin et al., 2011). Consequently, the current research proposes the following hypothesis:

Derived from the aforementioned structural relations from the hypotheses based on empirical studies, the hypothesized research model was developed.Figure 1:

Methods

Participants

This study utilized an online survey to collect data from physical education professors in northeast province, China. The non-probability sampling method of convenience sampling was employed, with an initial pool of potential participants identified from the physical education professors in the northeast province. The author sent out emails including an invitation message, a research description, and the study proposal, followed by a second email containing a survey link to Tencent Questionnaire. Of the 300 physical education professors who received the survey link, 236 responded, for a response rate of 78.67%. However, 44 responses were invalidated because they coded all survey items as either one or seven, resulting in a total of 192 responses used in the data analysis.

Among the participants, 56.3% (n = 108) were male, with an average age of 38.33 years (SD = 8.796). The majority, 53.6% (n = 103), had less than a decade of teaching experience. The educational qualification of most participants was either a master’s degree or an undergraduate degree. When queried about the courses they taught, they indicated that 37.5% (n = 72) taught practical courses, 34.4% (n = 66) taught both practical and theoretical courses, and 28.1% (n = 54) taught only theoretical courses. An overwhelming 93.8% (n = 180) of participants were affiliated with public universities. Among the professional ranks, assistant professors constituted the largest group at 43.2% (n = 83). The largest proportion of participants, 31.3% (n = 60), reported a monthly income in the range of 4001–6000 Chinese Yuan.

Instrument

The study employed a total of 18 survey items to measure four variables: emotional dissonance, perceived organizational support, job satisfaction, and turnover intention. Each variable was measured using various items: three for emotional dissonance, four for perceived organizational support, eight for job satisfaction, and three for turnover intention. Additionally, all measurement items selected for this study were originally written in English and Korean. Thus, the current study used the back-translation method recommended by Brislin (1970) to ensure the accuracy of translation in Chinese.

Emotional dissonance: This study adopted Morris and Feldman’s (1997) measure, as modified by Ha and Choi (2015), to evaluate the level of emotional dissonance among sports coaches. Responses were recorded on a seven-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). A sample item is “I hide my true feelings when I deal with students sometimes.”

Perceived organizational support: For this study, the perceived organizational support scales developed by Eisenberger et al. (1986) were adapted into a concise four-item format. Participants provided feedback using a seven-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). A modified sample item used by Eisenberger et al. (1986) is “The university values my contribution to its well-being.”

Job satisfaction: The job satisfaction measure was an adapted version of the subscale originally conceptualized by Guzzo (1979), with modifications by Ha and Choi (2015). Participants evaluated each statement on a seven-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). An example item of intrinsic job satisfaction is “I feel a sense of pride in my work,” while a sample item of extrinsic job satisfaction is “I perceive a relative balance between my work efforts and the monetary rewards received.”

Turnover intention: The turnover intention measure used in this study is a tailored version, originally crafted by Mobley (1982) and subsequently amended by Ha and Choi (2015). Participants responded using a seven-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). An example item of turnover intention is “If there is an opportunity to work at another university, then I would like to move to that university.”

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed utilizing SPSS 27.0 and AMOS 27.0. First, a frequency analysis was conducted to examine the demographic characteristics of the participants. Second, descriptive statistics, correlation analyses, and Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were calculated to examine the relationships among major latent factors and to assess the reliability of each measurement instrument. Third, a confirmatory factor analysis was conducted to verify the validity of the scales, inspecting both construct validity and composite reliability. Fourth, structural equation modelling was employed to evaluate the hypotheses of this research. In the third and fourth steps, the researcher conducted item parcelling of intrinsic job satisfaction and extrinsic job satisfaction. As noted by Ryu (2014), larger model sizes can impact fit indices due to increased complexity. Consistent with Ha and Choi (2015), this study employed item parcelling to enhance the measurement of model fit for the proposed models.

Results

Table 1 presents the descriptive statics (e.g. means, standard deviation), reliability estimates, and correlations among the variables. The study examined the potential for multicollinearity among variables, a concern which can arise when correlations between variables exceed .85 (Kline, 2005). The correlations were computed and revealed no correlation factors surpassing this threshold, indicating no multicollinearity problems. Furthermore, the reliability of the measurement scales was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha coefficients, with all values exceeding .70. According to Nunnally and Bernstein (1994), this indicates satisfactory reliability of the scales. With both multicollinearity and reliability concerns addressed, all constructs were deemed suitable for inclusion in subsequent analytical processes.

A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted to assess the fit of a measurement model comprising four latent constructs: perceived organizational support, emotional dissonance, job satisfaction, and turnover intention. Specifically, job satisfaction, which includes intrinsic job satisfaction and extrinsic job satisfaction, was reconstructed into new items using the item parceling technique. For example, in this study, job satisfaction consists of two sub-dimension (i.e., intrinsic and extrinsic job satisfaction). One indicator from each sub-dimension (i.e., intrinsic job satisfaction 1 and extrinsic job satisfaction 1) was selected. The two items were combined, and a mean score was derived as one indicator of job satisfaction. In this manner, four new indicators of job satisfaction, reflecting both sub-dimensions, were created for CFA.

The results indicated a satisfactory model fit: χ2/df= 1.882, p < .001, CFI = .960, GFI = .900, NFI = .920, RMSEA = .052. Table 2 presents the standardized factor loadings, error variances, average variance extracted (AVE), and construct reliabilities (CR). All factor loadings exceeded the recommended threshold of 0.5 (Stevens, 2012). The AVE values surpassed the benchmark of .50 (Fornell & Larcker, 1981), and the construct reliabilities exceeded the criterion of .70 (Bagozzi et al., 1998).

Additionally, the AVE for each construct was greater than the squared correlations among the constructs, demonstrating discriminant validity (Fornell & Larcker, 1981), as shown in Table 3. These findings support the conclusion that the observed variables effectively represent their respective latent constructs, indicating the robustness of the measurement model.

After confirming the measurement model fit the data well, structural equation modelling was employed to investigate structural relationships among latent variables. The structural model showed an acceptable model fit (χ2/df= 1.882, p < .001, CFI = .960, GFI = .900, NFI= .920, RMSEA = .052). Overall, the hypothesized structural model consisted of 4 factors (perceived organizational support, emotional dissonance, job satisfaction, and turnover intention). The results indicated that three of the six hypotheses were supported. The model showed that perceived organizational support had no significant relationship with emotional dissonance (β = −.014, p = .881), rejecting H1. Additionally, a positive and significant relationship was found between perceived organizational support and job satisfaction (β = .652, p< .001), supporting H2. Next, perceived organizational support had no significant relationship with turnover intention (β = −.229, p = .084), rejecting H3. Emotional dissonance had a negative and significant relationship with job satisfaction (β = −.191, p < .001), supporting H4. Job satisfaction had no significant relationship with turnover intention (β = −.252, p = .203) rejecting H5. Additionally, emotional dissonance had a negative and significant relationship with turnover intention (β = .230, p < .001), supporting H6.

Discussion

There are several key takeaways from the study findings. First, perceived organizational support showed no significant effect on emotional dissonance in the context of physical education professors, rejecting H1. This result can be theoretically contextualized through the lens of self-determination theory, developed by Deci and Ryan (1985), which posits that individuals are motivated by intrinsic and extrinsic factors. Intrinsic motivation, which is driven by internal rewards such as a sense of mastery, personal development, and enjoyment, can diminish the effects of external influences on behavior. Physical education professors who are inherently passionate about physical health and sports may exhibit a high level of intrinsic motivation and thus derive personal fulfilment from their roles. As a result, their intrinsic motivation may reduce their reliance on emotional dissonance as a coping mechanism to achieve their objectives, thus mitigating the impact of perceived organizational support on managing their emotions.

Second, perceived organizational support had a positive effect on job satisfaction, supporting H2. This is consistent with Eisenberger et al.’s (1986) finding that higher levels of perceived organizational support were related to increased job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and positive work behaviors. In the context of physical education in schools, these principles can be applied to understand how educators’ perceptions of support from their organization influence their job satisfaction. High levels of perceived support can lead to increased engagement, reduced stress, and a positive evaluation of their work, ultimately contributing to higher job satisfaction among physical educators. Research in education and organizational psychology has also demonstrated the importance of organizational support in fostering teacher well-being and job satisfaction (Dreer, 2024).

Third, perceived organizational support showed no significant effect on turnover intention, rejecting H3. This finding may be attributed to cultural factors, particularly the collectivist cultural values prevalent in China. Collectivist cultural norms value social harmony, loyalty, and adherence to authority (Hong et al., 2001). As a result, individuals in collectivist cultures like China may prioritize commitment and duty to their organizations, which can serve as a deterrent to turnover intention, regardless of their perceived levels of organizational support. This cultural influence aligns with the broader literature on the impact of culture on organizational behaviors and employee attitudes. Hofstede’s (1980) cultural dimension theory, for example, highlights the significant role of cultural values in shaping individuals’ behaviors and perceptions in the workplace, including their responses to perceived organizational support. Given the influence of collectivist cultural values in China, it is essential to recognize the substantial impact of culture on individuals’ decision-making processes and attitudes within the organizational context.

Fourth, emotional dissonance had a negative effect on job satisfaction, which is also consistent with prior studies (Alam & Asim, 2019; Ali, 2008), supporting H4. When professors experience emotional dissonance, it can result in emotional exhaustion, which is a component of burnout characterized by feelings of being overwhelmed and depleted of emotional resources (Maslach et al., 2001). According to the job demands-resources model, emotional exhaustion occurs when the emotional demands of a job surpass an individual’s ability to cope, leading to a depletion of their emotional resources (Bakker & Demerouti, 2007). Emotional exhaustion can significantly impact individuals’ well-being, job satisfaction, and overall functioning. As emotional resources are depleted due to emotional exhaustion, there is a decrease in enthusiasm, energy, and enjoyment associated with the job. According to the conservation of resources theory (Hobfoll, 1989), individuals strive to protect and nurture what they value. When they perceive a threat to these valued resources, such as consistent emotional dissonance leading to emotional exhaustion, the ultimate outcome is reduced well-being and job satisfaction.

Fifth, job satisfaction showed no significant effect on turnover intention, in contrast to the findings of Cunningham and Sagas (2004), rejecting H5. Meyer and Allen (1991) found that the relationship between job satisfaction and turnover intention is moderated and mediated by several factors, with organizational commitment being one of the key mediators. Organizational commitment, encompassing affective, normative, and continuance commitment, reflects an individual’s loyalty and attachment to the organization (Meyer et al., 1993). Additionally, individual differences and personal circumstances play a crucial role in influencing the job satisfaction–turnover intention relationship. For instance, research has shown that job alternatives in the labor market, financial stability, and individual career goals can moderate the impact of job satisfaction on turnover intention. Moreover, factors such as work–life balance priorities, opportunities for career growth, and organizational culture can also mitigate the impact of job satisfaction on turnover intention for certain individuals (Judge & Watanabe, 1993).

Sixth, emotional dissonance had a negative effect on turnover intention, supporting H6. The consistent suppression or fabrication of emotions in order to conform to professional expectations can result in psychological strain for individuals (Maslach et al., 2001). This strain can manifest as emotional exhaustion, causing employees to feel overwhelmed and lacking in emotional resources. Emotional exhaustion is one of three key components of job burnout as defined by Maslach et al. (2001), with the other two being depersonalization and reduced personal accomplishment. As employees experience persistent emotional dissonance, they are at risk of developing job burnout, which in turn is associated with an increased likelihood of turnover intention (Scanlan & Still, 2019).

A noteworthy finding in this study was that the mean value of emotional dissonance among physical education professors in China was relatively low. This indicated that there was minimal discrepancy between their genuine emotions and expressed emotions in their interactions with students. This could be attributed to the educator-centered educational culture and environment in Chinese universities, which allowed them to express their feelings more genuinely when dealing with students. However, due to the lack of research on emotional dissonance among physical education professors in China, it is necessary to conduct further studies to derive more objective and valid results in this field.

Implications

The identified relationships among emotional dissonance, perceived organizational support, job satisfaction, and turnover intention offer an important opportunity to enhance our current understanding of organizational behavior. The significant results in this study emphasize the need to reconsider and potentially reposition emotional dissonance within the broader framework of organizational behavior theory. Prior studies have focused on cognitive and behavioral aspects, with little emphasis on the significant impact of emotions in professions requiring consistent emotional dissonance (Gross & John, 2003). To fill this gap, it is essential to elevate the importance of emotional dissonance within theoretical constructs, particularly in the context of emotionally challenging positions, such as physical educators.

From a practical standpoint, these findings highlight the importance of proactive interventions. According to researchers like Grandey et al. (2005), emotional dissonance can be considered a skill that can be improved through intentional practice and repetition. Given the pervasive impact of emotional dissonance on physical education professors, it is crucial to design customized training programs that enhance emotional intelligence and regulation. These programs should go beyond equipping educators with tools to manage their emotions in isolation and instead aim to create an environment that promotes the emotional well-being of educators alongside the learning environment. The training programs should emphasize emotional regulation strategies to improve the well-being of educators and, as a result, contribute to a more conducive educational setting.

Limitations and Future Studies

While this study has contributed significantly to the extant literature on emotional dissonance within the context of physical education, it is imperative to acknowledge and address certain limitations. First, it is important to acknowledge that the sample used in this study consisted of physical education professors from a northeast province in China, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to the entire China or other countries. Therefore, research involving physical education professors from a wider range of universities should be conducted to derive more objective and generalizable outcomes.

Second, a primary limitation of the present study is its cross-sectional design, which restricts causal inferences. While the researcher formulated hypotheses based on existing literature, the study’s design does not allow for the establishment of cause and effect relationships. In future research, scholars may consider adopting repeated measures design to address this limitation.

Third, the impact of emotional dissonance on individual outcomes may be moderated by various moderating variables. For example, previous research has found that high job autonomy and perceived organizational support can moderate the relationship between emotional dissonance and outcomes. Future studies should consider investigating the role of these variables in the relationship between emotional dissonance and its outcomes.

Finally, further research is needed to explore the interplay between cultural factors and the impact of perceived organizational support on turnover intention in diverse cultural contexts. Further examination of these relationships would contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of the intricate association between organizational support and turnover intention.

Acknowledgments

This paper has been revised from the master’s thesis of the first author.

Author Contribution

Conceptualization: Xuantong Jin & Jaehyun Ha

Data curation: Xuantong Jin & Jaehyun Ha

Formal analysis: Xuantong Jin & Jaehyun Ha

Investigation: Xuantong Jin & Jaehyun Ha

Project administration: Xuantong Jin & Jaehyun Ha

Writing-original draft preparation: Xuantong Jin

Writing-review and editing: Jaehyun Ha

Figure and Tables

Table 1

Correlations, Cronbach’s alpha, means and standard deviations

Table 2

The results of factor loading, standard error, AVE, and CR

| Items | Factor loading | Std. Error | AVE | CR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ED1 | .785 | .113 | .571 | .841 |

| ED2 | .832 | .104 | ||

| ED3 | .731 | .112 | ||

| ED4 | .665 | .117 | ||

| POS1 | .791 | .106 | .697 | .902 |

| POS2 | .862 | .104 | ||

| POS3 | .876 | .097 | ||

| POS4 | .808 | .115 | ||

| JS1 | .898 | .070 | .726 | .914 |

| JS2 | .867 | .080 | ||

| JS3 | .849 | .075 | ||

| JS4 | .790 | .088 | ||

| TI1 | .739 | .126 | ||

| TI2 | .896 | .091 | .646 | .845 |

| TI3 | .768 | .117 |

Table 3

Squared correlations of each factor and AVE for discriminate validity

| Factor | ED | POS | JS | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ED | .571 | |||

| POS | .017 | .697 | ||

| JS | .077 | .331 | .726 | |

| TI | .064 | .102 | .099 | .646 |