The gender gap on women’s sports spectatorship

Article information

Abstract

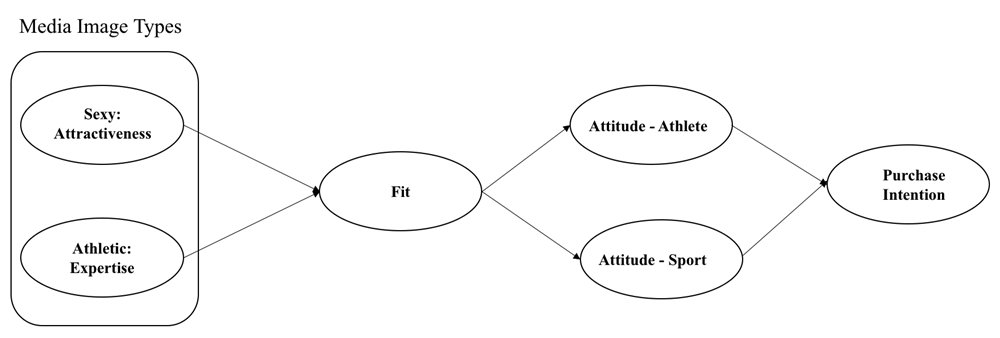

This study was to examine how different media images of female athletes’ impact women’s sports ticket sales for women’s sports spectatorship. This study interested in exploring the mechanism of buying a ticket for women’s sports event. The authors further analyzed what mechanism of women’s spectators’ intrigue to purchase the ticket for women’s sports event. As a theoretical framework, this study based on match-up hypothesis and associated learning theory to investigate spectators’ perceptions about female athletes’ presented media images on promoting their sport event ticket; this study explored (a) Fit: perceived appropriateness of the endorser (female athlete) with image type (athletic or sexy), and (b) Attitudes: how to fit impact on spectators’ attitude toward athlete and attitude toward sport separately, and (c) purchase intention to sport event. By adopting a 2×2 experiment design study, participants’ gender and image types manipulated. The participants (n = 113) were randomly assigned one of four conditions. The results indicated that the interaction between participants’ gender and image types was significant. Also, there was gender gap on women’s sports spectatorship in fit and attitude toward female athlete and women’s sport, and purchase intention to the sport event. The finding showed that male participants’ attitudes toward the athlete decreased more in response to the athletic image than the sexy image. Males preferred to see the sexy image while women do not want to see this type of image. Sports marketers need to know this perspective to sell their products and sporting event tickets. Thus, this study conclude that sex sells marketing does not promote women’s sports for either gender.

Introduction

The current study examined the context of women’s sports event, which has a long tradition of utilizing sexualized images of women in its promotional campaigns (Bruce, 2016; Fink, 2015; Weaving, 2016; Weaving & Samson, 2018). Women’s sports, especially women’s tennis event, is the most popular sport among professional women’s sports. Women’s tennis has traditionally had a more “feminine” emphasis than masculine sports such as softball or rugby (Werthein, 2002; Yip, 2018). The match-up hypothesis suggests that the strength of an association set in one’s mind depends upon the match between the product and the endorser. However, a longitudinal effect exists in the match-up hypothesis. An attractive (yet less expert) endorser may not initially create an active link with an athletic event in a consumer’s mind, but over time and repeated exposure, associative learning theory would suggest the link can forged (Cunningham, Fink, & Kenix, 2008; Fink, Cunningham, & Kensicki, 2004; Fink, et al., 2012). For example, in the case of female athlete models in Sports Illustrated’s swimsuit issue, media promoters of women’s sports often attempt to exploit female athletes’ sex appeal, athlete attractiveness, and expertise (Fink, 2015; Kim & Sagas, 2014; Kim, Sagas, & Walker, 2011). Women’s tennis may all be part of the same association set in consumers’ minds.

During the last few decades, media widely has been depicted as female athletes as sexual objects, even in the sport contexts (Bruce, 2016; Fink, 2015; Weaving, 2016; Weaving & Samson, 2018). The sexualization of women in sport takes for the granted social phenomenon to sports spectators’ perceptions. Numerous studies have explored this social phenomenon surrounding the treatment of gender and how the sports media displays the female athletes’ media images (e.g., Duncan, 1990, 1993; Fink, 2015; Frisby; 2017; Hull, et al, 2014; Kane, 1988; Koivula, 1995). However, only marginal empirical research has examined how media shape the perceptions of women’s spectatorship depend on different portrayals of female athletes’ media images. This media image should affect viewers’ attitudes toward those athletes and also women’s sport’ overall image eventually. Fasting (1999) speculated how people’s beliefs might influenced by biased coverage. This biased coverage was related to the actual consequences of various portrayals. Thus, further research needs to the extent to which type of media images can genuinely influence spectators’ perceptions toward women’s sports events. This aspect should further need to explore through the images for women’s sport event ticket sale (Knight & Giuliano, 2001). Previous studies mainly focused on the media research trend with content analysis about media representation of women in sports magazines (Kim, Sagas, & Walker, 2011; Kim & Sagas, 2014). Spectators’ perceptions and opinions remain still a relatively unknown areas to explore (Daniel & Wartena, 2011; Frisby, 2017; Hull, et al, 2014; Kane & Maxwell, 2011; Knight & Giuliano, 2001). Previous research on the psychological study has documented the negative impact of sexualized images. These study mentioned that negative media messages influence on female spectators’ perceptions of their individual bodies (Daniel, 2009; Grabe, Ward, & Hyde, 2008; Groesz et al., 2002) while to a lesser extent literature has examined the media impact on boys’ and men’s perceptions about female athletes through media representation (Aubrey & Taylor, 2009; Daniel & Wartena, 2011; Hargreaves & Tiggemann, 2002, 2003).

Furthermore, previous research has focused on the sexualized or gendered media images of female athletes and how these images impact attitude toward female athletes and toward women’s sporting images among men and women (e.g., Daniel, 2009; Daniel & Watena, 2011; Kane & Maxwell, 2011). The effectiveness of sex appeal marketing and gender gap of spectators on women’s spectatorship should be examined. The current study more focused on exploring what factors influence on buying women’s sports event ticket and how this mechanism intertwined into women’s sports spectatorship. Thus, the purpose of the current study seeks to determine how spectators’ gender perceives female athlete media images differently in order to develop gender-focused recommendations for sports marketing for women’s sport.

Thus, the current study directly investigated the media images of a female sports celebrity as perceived appropriateness for understanding women’s sports spectatorship. With one of the most marketable female athletes, well-known, a popular women’s sport, the current study could explore the effective marketing strategies by exploring the buying ticket behaviors (purchase intention) depend on promotion media images for women’s sports event. This should be helpful in understanding the effectiveness of media types of female athletes in women’s sport. Using the female athlete with two different types of media images (athletic vs. sexy) helps explain which image type is better to promote women’s sports in terms of improving women’s sports marketing strategies (Linder & Daniels, 2018; Daniels, el al., 2020). More specifically, this study also investigates how different types of media images impact spectators’ attitude toward the athlete (i.e., Sharapova) and sport (here, women’s tennis) as well as purchase intention of a sporting event ticket.

Literature Review

Contextual background: Sex Appeal Marketing on Women’s sport

Media representation of female athletes was often displayed provocatively or with overt sexual undertones in an attempt to capture the attention of heterosexual males even in the sport context (Daniels, 2009; Daniels & Watena, 2011; Fink, 2015; Weaving, 2016; Kane & Maxwell, 2011). Thus, female athletes commonly presented in “sexy” or sexually suggestive poses for photo spread in mainstream media (Fink, 2015; Hull, et al., 2014; Kim, Sagas, & Walker, 2011; Kim & Sagas, 2014). Also, the depiction of female athletes in the media shown through a male heterosexual fan perspective (Linder & Daniels, 2018; Kolnes, 1995; Krane, 2001). Many female athletes have allowed themselves to be portrayed as sexual objects or as overtly feminine as a survival strategy, which has created a paradox in those females accepted in sports, but only as long as they preserve their heterosexual attractiveness (Linder & Daniels, 2018; Kolnes, 1995). When a female athlete develops a heterosexual, feminine persona and cultivates such images, she is more likely to benefit from increased media attention, endorsements, fan approval, and reduced heterosexist discrimination (Kolnes, 1995).

The sexualization of female athletes in print and visual media have well researched for several decades (Christopherson, Janning, & McConnell, 2002; Daniels & Wartena, 2011; Davis, 2010; Fink, 2015; Kim et al., 2011; Messner, Duncan, & Cooky, 2003; Weaving, 2016). As evidence of this phenomenon, an increasing number of female athletes have depicted in sexually provocative ways in magazines such as Maxim, Playboy, and FHM (Daniels & Wartena, 2011). Sports Illustrated also began using female athletes as swimsuit models during the last 20 years already (Hagerman, 2001; Kim et al., 2011; Kim & Sagas, 2014; Weaving, 2016). Although the “sex sells” marketing strategy prevails, it is crucial to consider its negative consequences and impacts on society as a whole. This magazine displayed both female athletes and fashion models as sexually commercialized objects (Fink, 2015; Kim et al., 2011; Kim & Sagas, 2014; Weaving, 2016).

Methodological background: Experiments in spectators’ behavior of women’s sport

To understand what mechanism of spectators influence on their purchase behaviors, this study selected experiments design study to examine this topic. These previous studies conducted experiments to examine consumers’ perceptions toward athlete’s images through media representations (e.g., Daniels & Wartena, 2011; Knight & Giuliano, 2001; Lee & Koo, 2015; Linder & Daniels, 2018; O’Reilly, 2011). O’Reilly (2011) mentioned that “experiments in consumer psychology often involve consumers’ perceptions where the consumer has a few alternatives form which to select and where each one of the sets of alternatives defined by its associated specific attributes (p.218)”. This study used to fit between media image types of a female athlete appropriateness that may have contributed to the emphasis placed on the expertise and attractiveness of female athletes.

To understand the consumers’ gendered perceptions toward athletic and sexy media image, previous study examined consumer’s gender gap on the represented media images (Daniels & Wartena, 2011; Knight & Giuliano, 2001). Knight and Giuliano (2001) examined the media’s impact on people’s perception of athletes using two different types of written articles for both genders. They compared written articles about physical attractiveness and athleticism to examine media framing for viewers. Their study materials did not highlight sexualized athletes but instead used physically attractive athletes; also, written articles did not have a similar impact on viewers’ perceptions as photo images. Also, Daniels and Wartena (2011) intentionally investigated boys’ perceptions of female athletes by using open-ended questions. Their study specified sexualized and athletic female athlete images, comparing sexualized models with the athletes. The consumers’ perceptions of both genders not examined. The current study will examine both genders’ perceptions and their different approaches to female athlete’s media images using two different types of images (athletic or sexy).

The match-up hypothesis

The current study uses the match-up hypothesis as a theoretical framework (Lee & Koo, 2015; Liang & Lin, 2017; Till & Busler, 2000). The match-up hypothesis explains how the image of an endorsement, in conjunction with the image of a product, affects consumers’ product and advertisement evaluations (Lee & Koo, 2015; Liang & Lin, 2017; Till & Busler, 2000). According to the match-up hypothesis, the positive effects of endorsements only exist when a fit occurs between the image of endorsers and the image of a product (Kamins, 1990; Lynch & Schuler, 1994). Previous research (Agrawal & Kamakura, 1995; Kahle & Homer, 1985; Kamins, 1990; Ohanian, 1991; Solomon, Ashmore, & Longo, 1992; Till & Busler, 2000; Till & Shimp, 1998; Tripp et al., 1994) has generally supported the tenets of the match-up hypothesis. Till and Busler (2000) found that an athlete endorsing an energy bar brought about more favorable brand attitudes toward the energy bar than when the actor promoted the product. In other words, brand attitudes toward products were more positive, given the fit between the athlete’s expertise in the characteristics of a right energy bar and the energy bar. Veltri et al. (2003) found that young consumers were more likely to be influenced by athletes endorsing an athletic product. Other studies have revealed similar findings. Solomon et al. (1992) conducted an experiment design research to ascertain perceptions of women’s beauty and beauty types used in advertising in contemporary American culture. Their findings suggested that beauty is a multidimensional construct and that the fit between models and products depends on the classification of beauty the models represent. Kamins’ (1990) findings also indicate that an attractive person provides a particularly good fit when endorsing a product that is supposed to enhance consumers’ attractiveness, such as skin care lotions. Finally, the negative information about an athlete endorser, such as the athlete’s use of steroids, leads to negative consumer attitudes toward the brand in addition to the athlete (Till & Shimp, 1998).

Also, Till and Busler (2000) also found that the fit between the endorser and the product influences not only brand attitudes but also purchase intent. According to Ohanian (1991), perceived endorser expertise significantly affects a consumer’s purchase intention. Till and Busler (2000) revealed that, although physical attractiveness effected purchase intentions, the expertise of the source was more critical for matching a brand with the appropriate endorser. Furthermore, Tripp et al. (1994) found that, although the number of products a celebrity- endorsed increased consumers’ perceptions of his or her credibility, the attitudes toward the advertisement and intentions to purchase the products become less favorable. Thus, product-endorser fit plays an essential role in the generation of positive attitudes and purchase intentions toward a product.

In a sport context, An athlete’s expertise was a stronger fit for promoting a sporting event than the athlete’s attractiveness(Cunningham et al, 2008; Fink et al, 2012; Linder & Daniels, 2018). They extended their study with a tennis event, and then examined the interaction between expertise and attractiveness to determine the appropriateness of the endorser and sporting event (Cunningham et al., 2008). When using an endorser with physical attractive and great athletic performance skills, the fit is appropriate. Also, “female athletes’ sex appeal, athlete attractiveness, expertise, and women’s tennis may all be a part of the same association set (p. 376)”. More recently, Fink, Parker, Cunningham, and Cuneen (2012) examined gender-appropriate sports with sports product advertisement. They adapted social role theory and the match-up hypothesis to determine how gendered sports images promote sports products. They further investigated how consumers’ minds change by sports type. They found that athlete-product fit was the most critical determination of purchase intention for the advertised product, which is consistent with the match-up hypothesis. Moreover, they found no gender-appropriate sporting type to promote sports products.

Associated learning theory. The associated learning theory was adapted for this study to support the match-up hypothesis. This theory explains that different concepts can be linked or associated with consumers’ memory (Till & Shimp, 1998). In other words, once the patterns of concepts are linked together, they will lead to a connection in the memory, and each concept will gathered every time the other concept is elicited (Anderson, 1983; Klein, 1991; Till & Shimp, 1998). Even attitude—an individual’s evaluation of the brand and the celebrity—is considered an element of its association sets (Judd et al., 1991; Noffsinger, Pellegrini & Brunell, 1983). When endorsers are used to market products, it produces links with other concepts in consumers’ minds based on their experiences with and attitudes about both. In turn, the repeated pairings of the endorser and the product lead the product and the endorsers to become part of each other’s “association set”; when one of these two encountered, the other immediately comes to mind (Till & Bussler, 2000). Research findings (Hamm, Vaitl & Lang, 1989; Lynch & Schuler, 1994; Rozin & Kalat, 1971; Till & Busler, 2000) have suggested that the strongest of the association between the brand and the endorsers, the more likely the two concepts will become integrated within a network. This associative link has become a framework for predicting endorser effects.

Thus, the current study aimed to examine the influence of media images on spectators’ gender gap toward the spectatorship of women’s sport. A hypotheses were proposed based on this previous literature related to athletes’ physical attractiveness and expertise (Cunningham et al, 2008; Fink et al, 2012; Linder & Daniels, 2018). It predicted that interactions between spectators’ gender and female athletes’ presented media image types. Here are four variables: a) athlete-media image type fit (athletic or sexy), b) attitude toward athlete, c) attitude toward sport and d) purchase intention (women’s sports event ticket). Thus, four specific conditions examined: a male exposed to the athletic image, a female exposed to the athletic image, a male exposed to the sexy image, and a female exposed to the sexy image of a female athlete.

Hypothesis 1. The male spectators who exposed to the athletic image will give higher scores to perceived ‘fit’ as an appropriate endorser for the sport event.

Hypothesis 2. The male spectators who exposed to the athletic image will give higher scores to ‘attitude toward athlete’ than other three conditions.

Hypothesis 3. The male spectators who exposed to the athletic image will give higher scores to ‘attitude toward sport’ than other three conditions.

Hypothesis 4. The male spectators who exposed to the athletic image will give higher scores to ‘purchase intention’ than other three conditions.

Method

Participants

The participant were undergraduate students (N = 113) enrolled in sport management classes in the large university located on the southeastern US. This sample was 60 (53.1%) males and 53 (46.9%) females. The respondents ranged, in age, from 18 to 26 with a mean age of 19.95. Among the samples, 76(67.3%) were White, 21(18.6%) were African American, two (1.8%) were Asian, and 12 (10.6%) were Latino. Also, 99(87.6 %) of students were participating in sports activity, while 14 (12.4%) were not.

Procedure

To recruit research participants, the first author wrote an invitation letter to department advisors, program managers and classroom instructors with detailed information about this study. The invited class were related to sport management program courses of the undergraduate level. They get an extra credit incentive by voluntarily participating for this study.

This study employed a 2 (gender of participants: male, female) × 2 (Image type: athletic, sexy) full factorial design such that participants were randomly assigned to one of four conditions: Image of Athletic type (n = 56, m=30, f=26), sexy type (n = 57, m=30, f=27). As this study materials, two-color photographs of a female athlete, Maria Sharapova’s image used by searching Google Image in the present study. She is the most well-known female athlete as a physically attractive and high-performed female athletes (Fink, 2015). This study aims to capture the perception of the interaction between physical attractiveness and expertise in women’s sport context. Previous study proved that Maria Sharapova is an appropriate case for marketing and female athlete endorsement study (Fink et al., 2012; Gilbert, 2007; Lee et al., 2014). Also, most of participants could easily recognize a well-known female sport celebrity. For the athletic type condition, an image of Maria Sharapova in a tennis match was used. She was ready to hit the ball on the court and looked at the ball seriously in this photo. As for the sexy type condition, participants observed a photograph of tennis player Maria Sharapova wearing a white swimsuit and lying on the beach. This picture was selected and modified (by cutting the name of magazine in the image) from a popular sports magazine Sports Illustrated swimsuit issue edition.

This survey conducted by giving the online survey link to participants, In the first section of the online survey (Qualtrics), a brief introduction explained the purpose of the research. The time needed to complete the questionnaire, the respondents’ confidentiality explained. Participants informed that they are free to withdraw the study at any time without any consequences. In the next section, participants viewed the image before to complete the rest of the questionnaire. After viewing the picture, they completed questions or measures related to attitude toward the athlete and sport, athlete-body image fit. Ten questions were asked to the participants to indicate the level of agreement on a 9-point semantic differential scale along with a single open-ended question about the athletes’ pictures. At the end of the questionnaire, demographic information collected.

Measurements

The questionnaire requested participants to provide their age, ethnicity, and gender and sport participation related to the study variables. Reliability estimates (Cronbach’s alpha) for each measure in the questionnaire were calculated and reported below.

Athlete- media image type fit. The appropriateness of the athlete for the sport event was measured via adapted version of Till and Busler’s (2000) five item scale: “As an image for the sport event, I think she/he is appropriate,” “As an image for the sport event, I think she/he is effective,” “I think the combination of image for the sport event goes together well,” “I think the combination of image for the sport event is a good fit,” and “I think the combination of image for the sport event belong together.” Items measured on a 9-point semantic-differential scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 9 (strongly agree), the reliability estimate was high (α=.97).

Attitude toward athlete and sport. Following Till & Busler (2000), attitudes toward the athlete and sport assessed using three semantic differential scales in response to the following phrase, “In general, how do you feel about the athlete” and “In general, how do you feel about women’s sport?” The three scales were strongly dislike – strongly like, unfavorable – favorable, and negative – positive. All items measured on a 9-point semantic differential scale. The reliability for attitude toward athlete (α=.97) and attitude toward sport (α=.94) measures was high.

Purchase intention. Three items from Till and Busler (2000) used to measure intentions to purchase a women’s tennis event ticket. Participants responded to the following phrase, “How likely is it that you would consider purchasing a ticket to the sport event?” 9-point semantic differential scales anchored the phrase with endpoints unlikely – likely, definitely would not – definitely would, and improbable – probable. There was a high-reliability estimate for the measure (α=.96).

Data Analysis

To explore the impact of the independent variables, this study analyzed variance (ANOVA) procedures to assess the efficacy of the experimental manipulations on athlete-product appropriateness (fit), attitude toward athlete/sport, and purchase intention for sport event tickets. Means, standard deviations were computed for all variables (see Table 1). Hypotheses 1, 2, 3, and 4 tested through an analysis of variance, using SPSS 22.0 Version.

Results

Manipulation check

Manipulation check carried out to assess the different perception of participants’ gender and their views on the different types of images of female athletes: athletic type (n = 56) and sexy type (n = 57). Participants' responses were significantly difference (F 1, 112=9.317, p = .003) between athletic type (M=6.76, SD=2.41) and sexy type (M=7.89, SD=1.38). These results demonstrate the efficacy of the manipulations. Further, the absence of an interaction indicates that sexy type (attractiveness) and athletic type (expertise) did not confound.

Hypotheses Testing

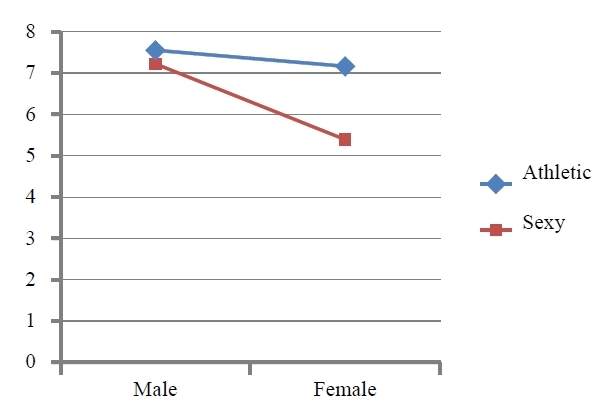

Hypothesis 1, 2, 3, 4 predicted an interaction between participants’ gender and media image dependent variables. In Table 1, ANOVA results indicate that two dependent variables among four had interaction effects; Fit (F 1, 112=5.901, p = 017) and attitude toward athlete (F 1, 112=4.384, p = .039) were significant. Attitude toward sport (F 1, 112=1.369, p = .245), and purchase intention (F 1, 112=1.839, p = .178) was not significantly different in this study. Correctly, means and standard deviations presented in Table 1. Most of the participants gave the highest point on the image of the athletic type. This study predicted that males who saw the athletic image of female athletes as an appropriate endorser for sport events would indicate a higher score than other conditions in hypothesis 1, 2, 3, 4 (see Table 1). As a significant finding, the athletic image of a female athletes was the highest score for male participants (M=7.55, SD=1.42). Female participants who saw the sexy image (M=5.39, SD=1.67) indicated low in athlete-media image fit (See Figure 1). Interestingly, males who saw the sexy image (M=7.22, SD=1.37) scored higher than females who saw the athletic image (M=7.16, SD=1.81). In the sexy type (see Figure 1), there was a big gap between males and females (Female: M=5.39, SD=1.66, Male: M=7.22, SD=1.37). So, we found support in hypothesis 1. There were significant differences in ‘fit of the endorser and product type’ by participants’ gender (F1, 112=5.901*, p = .017).

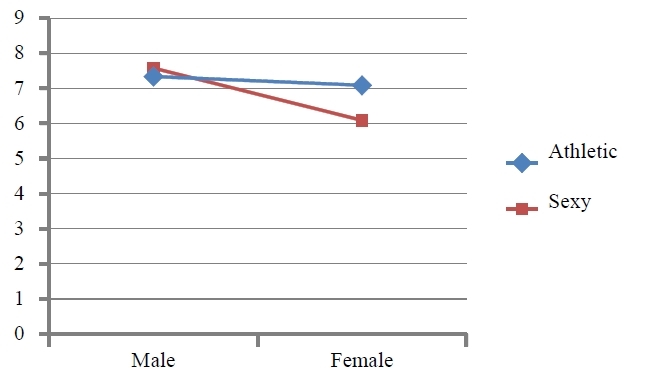

In ‘attitude toward athlete’, this study also predicted that males who saw the athletic image would indicate a higher score than other conditions in hypothesis 2. There are significant interaction differences in attitude toward athletes (F 1, 112=4.384*, p = .039). In Table 1, however, male participants who saw the sexy type image (M = 7.58, SD = 1.29) of the female athlete was more score than athletic type (M = 7.34, SD = 1.60). Interestingly, male participant’s scores increased when they saw the sexy images of a female athletes than the athletic images (See Figure 2). However, female participants still gave a higher score in athletic type (M = 7.09, SD = 1.71) than sexy type (M = 6.08, SD = 1.66). Female participants were dramatically decreased their score from athletic type to sexy type and negatively saw sexy type image of a female athlete. We failed to support hypothesis 2.

The hypothesis 3 predicted ‘attitude toward sport’ would give the highest score for male participants in the athletic image of a female athlete (see Table 1). Male who saw athletic image of female athlete (M = 7.33, SD = 1.60) were highest rank than female participants (M = 6.00, SD = 2.03) who saw the athletic image. Females who saw the sexy image (M = 5.12, SD = 2.00) indicated the lowest score than male participants (M = 7.25, SD = 1.56). We found support in hypothesis 3. However, there is no statistical difference in attitude toward sport (F 1, 112=1.369, p = .245).

Finally, the authors predicted males who saw the athletic image of a female athlete would indicate a higher score than the other three conditions to purchase tickets for women’s sports event in hypothesis 4. However, females who saw the athletic image of a female (M = 5.55, SD = 2.55) were the highest score in purchase intention than males (M = 5.35, SD = 2.29) who saw the athletic image (see Table 1). These results did not support Hypothesis 4. Also, there is no significant interaction difference in purchase intention (F 1, 112=1.839, p = .178). Female participants also gave the lowest score in sexy type image (M = 3.60, SD = 2.01) while male participants (M = 4.63, SD = 2.65) in a sexy image.

Discussion

The current study designed to address how do women’s sport spectators have purchase intention depend on particular media images of female athletes, and how do those ticket-buying mechanisms influence their interest in women’s sports spectatorship. Further, this study also examined how does spectators’ gender influences the interpretation of a media image. Given the great biased perspectives of male spectators about women’s sports and female athletes’ images in the media, this study focused on spectators’ gender differences related to female athlete images. The current study predicted that the athletic image of the female athlete would get more favorable ratings than the sexy image of the female athlete on every individual dependent variable.

As one of the major findings of the current study, the athletic image of the female athlete was shown to positively impact the perspectives of spectators’ both genders in fit and attitude toward sports. However, media image type was not directly increase purchase intention to the women’s sport event (The hypothesis 4 was not supported). The author interpreted that sex appeal marketing for women’s sport event is not the best way to promote women’s sport. Thus, our result indicated that male spectators did not want to purchase a ticket for women’s sport. According to Fink et al, (2012), the type of sport an athlete plays might not be a key determinant of celebrity endorsement effects. In addition, a few opposite gender differences emerged in attitude toward athlete and purchase intention of a sporting event ticket. As a result of attitude toward athlete, male spectators’ points were higher in the sexy image of the female athlete than the athletic image, while female consumers’ points decreased in the sexy image. Based on this result, female athletes’ attractiveness appears to be a more compelling factor for increasing positive attitude toward athletes than her expertise, for male spectators. However, this result contradicts the findings of previous studies. For example, Daniels and Wartena (2011) found that boys gave neutral or negative comments on the sexualized athlete’s athleticism but positive comments about the performance athlete’s physical competence. Kane and Maxwell (2011) found that female athletes’ sexy images do not seem to elicit positive comments on women’s athleticism. Although these studies did not distinguish attitude toward the athlete and attitude toward women’s sports, no positive results found about female athletes’ sexy image on viewers’ perspectives in previous studies. Meanwhile, the current study demonstrated that the “sex sells” marketing strategy works for male spectators but does not fit female spectators. Thus, this study concluded that spectators’ gender gap still existed in their perceptions of sports marketing with the female athlete media images, especially the female athlete’s sexualization.

As this study found above, male spectators demonstrated more positive perspectives on the sexy image of the female athlete. However, this finding only related to their attitude toward the athlete. Although male spectators more positively viewed the attractive female athlete in the sexy image than in the athletic image, they also negatively viewed women’s sports when presented with a sexy image of the female athlete. Thus, we conclude that sex sells marketing does not promote women’s sports for either gender. Similar to the findings of Daniels and Wartena (2011) and Kane and Maxwell (2011), the current research results indicated that the athletic image was more appropriate for promoting sporting events than the sexy images of the athlete. However, male participants’ attitudes toward the athlete decreased more in response to the athletic image than the sexy image. Males preferred to see the sexy image while women do not want to see this type of image. Sports marketers need to know this perspective to sell their products and sporting event tickets. Although associative learning theory suggests that links between concepts can created, the strength and effectiveness of the association depend on how well the concepts match up and how the endorser appeals to audiences (Kamins, 1990; Klein, 1991).

This study found that gender differences exist among spectators regarding the female athlete’s two types of media images. Responses to the structured questions highlighted where differences in each specific dependent variable exist; collecting statistical data on individual variables provided a more precise understanding. The data demonstrated that the sexualization of women in sport debate emerged in discussions of both types of images, not only from the sexy image, which suggested how and why participants intended to participate in personal opinions. Spectators’ perspectives toward the female athlete images operationally defined by ratings and showing relationships between each variable in the traditional experimental design study (Cunningham et al., 2008; Fink, Cunningham & Kensicki, 2004; Fink et al., 2011). Similar to the finding of the previous research (Cunningham et al., 2008; Fink, Cunningham & Kensicki, 2004), perceptions of athlete-event appropriateness as a factorial event endorser were related to positive attitude toward the event and were related to purchase intentions. Still, physically attractive female sport celebrity endorsers are successful in marketing a product or service that targeted for men’s spectators. Meanwhile, participants in the current study indicated that such instrumental measurements did not allow them to provide sufficient explanation. The current study sought to address this issue by analyzing sources of gender differences in empirical research on a female athlete’s images on women’s sports spectatorship and by gathering data on both women’s and men’s intentions. This study offers methodological improvements and research directions that may provide the basis for new models of the media uses of sports marketing from both genders’ perspectives.

Limitations and Directions for Future Research

Although the previous study suggested that future study should attempt to use real athletes and sport event (Cunningham et al., 2008), using a female sports celebrity, Maria Sharapova (tennis player) in a fictitious event is still limited in its generalizability to actual events. Future studies should attempt to replicate the study employing real events such as the U.S. Open. In addition, the future researcher should care must be taken to minimize confounding variables in such studies (e.g., athlete personality, race, reputation, ranking, popularity). Characteristics of athletes may also shape consumers’ perceptions of athlete-event appropriateness (fit). In particular, an athlete’s persona, familiarity, or likeability may influence fit with various events. Although Maria Sharapova and Serena Williams often recognized the high-performed professional athletes in Women’s tennis, they exhibited very different personas both on and off the courts. They were endorsed in very different types of products. Consumers’ perceived fit at different events, different product.

Also, a convenience student sample can only reveal a narrowed scope of spectatorship on women’s sport and behaviors. Because young adults’ perceptions of fit, attitude, and purchase intention are also different from those of other populations, thereby indicating another limitation of this research. Because the spectators’ assessment of the endorser on event fit builds upon a complex environment, other conditions should consider. For example, participants’ knowledge about the sport and/or following the sport jointly may influence their judgments. As Kahle and Homer (1985) indicated, the level of involvement with the product (or, in the current case, event) influences participants’ processing of advertisements.

References

Agrawal, J., & Kamakura, W.A. (1995). The economic worth of celebrity endorsers: An event study analysis. Journal of Marketing, 59, 56-62.

10.1177/002224299505900305.Anderson, John R. (1983). A spreading activation theory of memory. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 22(3), 261-295.

10.1016/S0022-5371(83)90201-3.Aubrey, J. S., & Taylor, L. D. (2009). The role of lad magazines in priming men’s chronic and temporary appearance-related schemata: An investigation of longitudinal and experimental findings. Human Communication Research, 35, 28-58.

10.1111/j.1468-2958.2008.01337.x.Bruce, T. (2016). New rules for new times: Sportswomen and media representation in the third wave. Sex Roles, 74(7-8), 361-376.

10.1007/s11199-015-0497-6.Christopherson, N., Janning, M., & McConnell, E. D. (2002). Two kicks forward, one kickback: A content analysis of media discourses on the 1999 Women’s World Cup Soccer Championship. Sociology of Sport Journal, 19, 170-188.

10.1123/ssj.19.2.170.Crawford, M., & Gressley, D. (1991). Creativity, caring, and context. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 15, 217-231.

10.1111/j.1471-6402.1991.tb00793.x.Creswell, J. W. (2003). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (2nd edition). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publication.

Cunningham, G. B., Fink, J. S., & Kenix, L. S. (2008). Choosing an endorser for a women’s sporting event: The interaction of attractiveness an expertise. Sex Roles, 58, 371-378.

10.1007/s11199-007-9340-z.Daniel, E. A., & Wartena, H. (2011). Athlete or sex symbol: What boys think of media representations of female athletes. Sex Roles, 65(7/8), 566-579.

10.1007/s11199-011-9959-7.Daniels, E. A. (2009). Sex objects, athletes, and sexy athletes: How media representations of women athletes can impact adolescent girls and college women. Journal of Adolescent Research, 24, 4, 399-422.

10.1177/0743558409336748.Daniels, E. A., Hood, A., LaVoi, N. M., & Cooky, C. (2020). Sexualized and Athletic: Viewers’ Attitudes toward Sexualized Performance Images of Female Athletes. Sex Roles, 1-13.

10.1007/s11199-020-01152-y.Davis, P. (2010). Sexualization and sexuality in sport. In Davis, P. & Weaving, C. (Eds.), Philosophical perspectives on gender in sport and physical activity (pp.57-63). New York: Routledge.

10.4324/9780203885550.Duncan, M. C. (1990). Sports photographs and sexual difference: Images of women and men in the 1984 and 1988 Olympic Games. Sociology of Sport Journal, 7, 22-43.

10.1123/ssj.7.1.22.Duncan, M. C. (1993). Beyond analyses of sport media texts: An argument for formal analyses of institutional structures, Sociology of Sport Journal, 10, 353-372.

10.1123/ssj.10.4.353.Fasting, K. (1999). Women and sport. Olympic Review, 26, 43-45.

Fink, J. S., Cunningham, G. B., & Kensicki, L. J. (2004). Using athletes as endorsers to sell women’s sport: Attractiveness versus expertise. Journal of Sport Management, 18, 350-367.

10.1123/jsm.18.4.350.Fink, J. S., Parker, H. M., Cunningham, G. B., & Cuneen, J. (2012). Female athlete endorsers: Determinants of effectiveness. Sport Management Review, 15(1), 13-22.

10.1016/j.smr.2011.01.003.Fink, J. S. (2015). Female athletes, women's sport, and the sport media commercial complex: Have we really “come a long way, baby”?. Sport Management Review, 18(3), 331-342.

10.1016/j.smr.2014.05.001.Frisby, C. (2017). Sexualization and objectification of female athletes on sport magazine covers: Improvement, consistency, or decline?. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 7(6), 21-32.

Gilbert, S. J. (2007). Marketing Maria: Managing the athlete endorsement. Working Knowledge. Harvard Business School.

Glenny, E. G. (2006). Visual culture and the world of sport. The Scholar & Feminist Online, 4(3). 4

.Grabe, S., Ward, L. M., & Hyde, J. S. (2008).The role of the media in body image concerns among women: A meta-analysis of experimental and correlational studies. Psychological Bulletin, 134, 460-476.

10.1037/0033-2909.134.3.460.Groesz, L. M., Levine, M. P., & Murnen, S. K. (2002). The effect of experimental presentation of thin media images on body satisfaction: A meta-analytic review. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 31, 1-16.

10.1002/eat.10005.Hagerman, B. M. (2001). Skimpy coverage: Sportswomen in Sports Illustrated, 1954-2000. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Ohio University.

Hamm, A. O., Vaitl, D., & Lang, P. J. (1989). Fear Conditioning, Meaning, and Belongingness: A Selective Association Analysis. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 98(4), 395-406

. 10.1037/0021-843X.98.4.395.Hargreaves, D. A., & Tiggemann, M. (2002). The effect of television commercials on mood and body dissatisfaction: The role of appearance-schema activation. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 21, 287–308.

10.1521/jscp.21.3.287.22532.Hargreaves, D. A., & Tiggemann, M. (2003). Female “thin ideal” media images and boys’ attitudes toward girls. Sex Roles, 49, 539–544.

10.1023/A:1025841008820.Hull, K., Smith, L. R., & Schmittel, A. (2015). Form or Function? An Examination of ESPN Magazine's “Body Issue”. Visual Communication Quarterly, 22(2), 106-117.

10.1080/15551393.2015.1042159.Judd, C. M., Drake, R. A., Downing J. W., & Krosnick, J. A. (1991). Some dynamic properties of attitude structures: Context-induced response facilitation and polarization. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60(2), 193-202.

10.1037/0022-3514.60.2.193.Kahle, L. R., & Homer, P. (1985). Physical attractiveness of the celebrity endorser: A social adaptation perspective. Journal of Consumer Research, 11, 954-961.

10.1086/209029.Kamins M. A. (1990). An investigation into the match-up hypothesis in celebrity advertising: When beauty may only be skin deep. Journal of Advertising, 19(1), 4-13.

10.1080/00913367.1990.10673175.Kane, M. J. (1988). Media coverage of the female athlete before, during and after title IX: Sports Illustrated revisited. Journal of Sport Management, 2, 87-99.

10.1123/jsm.2.2.87.Kane, M. J. & Maxwell, H. D. (2011). Expending the boundaries of sport media research: Using critical theory to explore consumer responses to representations of women’s sports. Journal of Sport Management, 25, 202-216.

10.1123/jsm.25.3.202.Kim, K., Sagas, M., & Walker, N. A. (2011). Replacing athleticism with sexuality: Athlete models in Sports Illustrated swimsuit issues. International Journal of Sport Communication, 4(2), 148-162.

10.1123/ijsc.4.2.148.Klein, S. B. (1991). Learning: Principles and applications. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Knight, J. L. & Guiliano, T. A. (2001). He’s Laker; she’s a “Looker”: The consequences of gender-stereotypical portrayals of male and female athletes by the print media. Sex Roles, 45, ¾. 217-229.

10.1023/A:1013553811620.Koivula, N. (1995). Ratings of gender appropriateness of sports participation: Effects of gender-based schematic processing. Sex Roles, 33, 543-557.

10.1007/BF01544679.Kolnes, L. J. (1995). Heterosexuality as an organizing principle in women's sport. International Review for Sociology of Sport, 30, 61-77.

10.1177/101269029503000104.Krane, V. (2001). We can be athletic and feminine, but do we want to? Challenging hegemonic femininity in women's sport. Quest, 53, 115-133.

10.1080/00336297.2001.10491733.Lee, S., Kim, W., & Kim, E. J. (2014). The extended match-up hypothesis model: the role of self-referencing in athlete endorsement effects. International Journal of Sport Management and Marketing, 15(5-6), 301-321.

10.1504/IJSMM.2014.073212.Lee, Y., & Koo, J. (2015). Athlete endorsement, attitudes, and purchase intention: The interaction effect between athlete endorser-product congruence and endorser credibility. Journal of Sport Management, 29(5), 523-538.

10.1123/jsm.2014-0195.Liang, H. L., & Lin, P. I. (2018). Influence of multiple endorser-product patterns on purchase intention. International Journal of Sports Marketing and Sponsorship, 19(4), 415-432.

10.1108/IJSMS-03-2017-0022.Linder, J. R., & Daniels, E. A. (2018). Sexy vs. sporty: the effects of viewing media images of athletes on self-objectification in college students. Sex Roles, 78(1-2), 27-39.

10.1007/s11199-017-0774-7.Lynch, J. & Schuler, D. (1994). The matchup effect of spokesperson and product congruency: A schema theory interpretation. Psychology & Marketing, 11(5), 417-445.

10.1002/mar.4220110502.Messner, M. A., Duncan, M. C., & Cooky, C. (2003). Silence, sports bras, and wrestling porn. Journal of Sport & Social Issues, 27, 38–51.

10.1177/0193732502239583.Morgan, D. L. (1998). Practical strategies for combining qualitative and quantitative methods: Applications to health research. Qualitative Health Research, 8(3), 362-376.

10.1177/104973239800800307.Noffsinger, E. B., Pellegrini, R. J., & Brunell, G. M. (1983). The Effect of associated persons upon the formation and modifiability of first impressions. Journal of Social Psychology, 120(2), 183-195.

10.1080/00224545.1983.9713211.Ohanian, R. (1991). The impact of celebrity spokespersons’ perceived image on intention to purchase. Journal of Advertising Research, 31(1), 46-54.

O’Reilly, N. (2011). Experimental design methods in sport management research: The playoff safety bias. Journal of Sport Management, 25, 217-228.

10.1123/jsm.25.3.217.Rozin, P., & Kalat, J. W. (1971). Specific hunger and poison avoidance as adaptive specializations of learning. Psychological Review, 78(6), 459-486.

10.1037/h0031878.Solomon, M., Ashmore, R., & Longo, L. (1992). The beauty match-up hypothesis: Congruence between types of beauty and product images in advertising. Journal of Advertising, 21(4), 23-34.

10.1080/00913367.1992.10673383.Till, B. D. & Busler, M. (2000). The match-up hypothesis: Physical attractiveness, expertise, and the role of fit on brand attitude, purchase intent, and brand beliefs. Journal of Advertising, 29(3), 1-14.

10.1080/00913367.2000.10673613.Till, B. D. & Shimp, T. A. (1998). Endorsers in advertising: The case of negative celebrity information. Journal of Advertising, 27(1), 67-82.

10.1080/00913367.1998.10673543.Tripp, C., Jensen, T.D., & Carlson, L. (1994). The effects of multiple product endorsements by celebrities on consumers’ attitudes and intentions. Journal of Consumer Research, 20, 535-547.

10.1086/209368.Veltri, F. R., Kuzma, A. T., Stotlar, D. K., Viswanathan, R., & Miller, J. J. (2003). Athlete-endorsers: Do they affect young consumer purchasing decision? International Journal of Sport Management, 4, 145-160.

Weaving, C. (2016). Examining 50 years of ‘beautiful’ in Sports Illustrated Swimsuit Issue. Journal of the Philosophy of Sport, 43(3), 380-393.

10.1080/00948705.2016.1208534.Weaving, C., & Samson, J. (2018). The naked truth: disability, sexual objectification, and the ESPN Body Issue. Journal of the Philosophy of Sport, 45(1), 83-100.

10.1080/00948705.2018.1427592.Werthein, J. L. (2002). Venus Envy: Power games, teenage vixens, and million-dollar egos on the women’s tennis tour. New York, NY: Harper-Collins Publishers.

Yip, A. (2018). Deuce or advantage? Examining gender bias in online coverage of professional tennis. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 53(5), 517-532.

10.1177/1012690216671020.