Physical Theater Class Experiences: Mental Health, Play, and the Love of Movement

Article information

Abstract

Mental health issues, especially among young women, have significantly increased due to Covid-19 pandemic. Although movement activities in Kinesiology and performing arts can have countless health benefits, physical activity declines drastically among mainly freshmen and young females. The purpose of this study was to examine the effects of physical theater (e.g., dance, aerial dance, calisthenics, strength training, balance, coordination, flexibility, and bodily expression) on mental health, healthy lifestyles, play, and the love of movement among college students. This was a mixed-methods, phronetic and temporal study encompassing quantitative and qualitative data among seven undergraduate students, who enrolled in a physical theater class. Dependent t-tests were conducted to examine differences in depression and stress between the beginning of the class and the end of the semester. Phronetic research was used to analyze the qualitative data and create themes and categories. Mental health improved with a nearly medium within-subject effect for stress (d = .32, Mdifference = 3.5). These data were strengthened by the three emerging themes of the qualitative analysis. The first theme, positive physical theater experiences, included body confidence in expression, improved mental health, healthier lifestyle choices, and the love of movement. The second theme showcased the playful nature of physical theater (e.g., a non-purposeful, interactive, child-like activity, outside ordinary life). A few participants mentioned a couple of negative physical theater experiences (third theme), such as injury and darkness in expression. Movement educators in Kinesiology and performing arts should emphasize safe, bodily, creative, and playful activities within a supportive and community-oriented environment for the promotion of health and the love of movement.

Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO, 2022a) reports that there has been a 25% increase in anxiety and depression worldwide due to Covid-19 pandemic. Young adults and women have been worst hit. Similarly, the latest report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) shows that nearly 1 in 4 young adults, especially women, received mental health treatment in 2021 due to Covid-19 pandemic (McPhillips, 2022). Some reasons for the rapid and vast mental health decline, especially among young adults and women, include social isolation, employment constraints, financial worries, and exhaustion (notably among health workers) (WHO, 2022a). High depression and stress levels are associated with decreased functioning and quality of life, increased risk of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and obesity morbidity (Penninx et al., 2013; Rajan & Menon, 2017). They are also linked to self-harm and suicidal attempts, especially among college-level students (Liu et al., 2019; WHO, 2022b).

Although participation in physical activity significantly decreases stress and depression levels (Mikkelsen et al., 2017), many college students are not physically active. The greatest temporal declines in physical activity levels occur among freshmen and young females (Corder et al., 2016; Lackman et al., 2015). Enjoyable, long-term physical activity participation is also a challenge, especially among young adults with high social pressures to succeed academically and become financially independent (Kosma et al., 2021a). It is therefore timely and important to examine physical activity or movement programs that are exciting and motivating among college students. In this paper, physical activity is holistically defined to include fitness and sports elements within performing arts (physical theater), including dance and aerial dance, calisthenics, as well as individual and group-based physical play (e.g., performing breakfalls and martial arts movements/“fighting” with stage combat swords) (Kosma, 2021, 2022, 2023; Kosma & Erickson, 2020a, 2020b; Kosma et al., 2021a, 2021b, 2023; Piggin, 2020; WHO, 2022b).

Drawing on Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics (Aristotle, 350 BCE/1962), ever-changing, time and context-specific life experiences (praxis) can lead to the knowledge of phronesis (practical/moral wisdom or reasoning), whereby people can strengthen their autonomy and free will to make wise decisions about leading the good life (Buchanan, 2006, 2016; Flyvbjerg, 2001, 2004). Decisions about human action like physical activity are based on one’s value system, which is formed by their history, cultural upbringing, and socio-political structures – process of phronesis (Kosma, 2022; Kosma & Buchanan, 2018a, 2018b, 2019; Kosma & Erickson, 2020a; Kosma et al., 2015, 2017, 2021a). For example, children who are encouraged to play and be active tend to sustain this behavior later in life (Bélanger et al., 2015; Kosma, 2021, 2022, 2023; Kosma & Buchanan, 2018b). People’s valued goals are normative in nature and not merely individualistic desires (Buchanan, 2016; Kosma, 2021; MacIntyre, 2015; Wolf, 2010). The worth of leading healthy lifestyles can be highly appreciated and valued across many communities and societies nationally and internationally (Kosma, 2021, 2022). Given the added pressures and challenges during the Covid-19 pandemic, achieving quality of life (a normative good) can be challenging (Kosma et al., in press). Young adults may wonder if they have time, energy, enthusiasm, and the financial resources to be active and cook a healthy meal at home. Do they have quality leisure time to be able to sense and appreciate the good life and healthy lifestyles? (Kosma et al., in press).

It has been showcased that involvement with performing arts like dancing and aerial dancing within a physical theater setting translates into meaningful movement-based leisure activities for young adults’ health, healthy lifestyles, and the love of movement (Kosma & Erickson, 2020a, 2020b; Kosma et al., 2021a, 2023). These physically demanding artistic activities are considered phronetic in nature because they are done for their own sake, for the sheer joy of the experience (Kosma & Erickson, 2020a, 2020b; Kosma et al., 2021a, 2021b). A key element in those bodily activities is the performativity aspect like creating a choreography or story to physically share with others (Bowditch et al., 2018; Kosma & Erickson, 2020a; Kosma et al., 2021a, 2021b). Bodily expression or physical storytelling in performing arts is a key characteristic of physical theater. Instead of relying on dialogue to communicate, in physical theater the performer will use corporeal techniques like calisthenics, body posture and awareness, dance work, physical play (e.g., “fighting” with stage combat swords, performing breakfalls), mime, gestures, stance, status (distance, strength of contact), proximity (distance from other performers), and masks (Bowditch et al., 2018; Hanlon, 2021; Kosma & Erickson, 2020a, 2020b; Kosma et al., 2021a, 2021b, 2023). The playful nature of physical theater – one of its key elements – can make the movement/physical experiences enjoyable for life (Gadamer, 1975/2012; Huizinga, 1950; Kosma & Erickson 2020a, 2020b; Kosma et al., 2021a, 2021b). True play is supposed to be non-purposeful, outside ordinary life (e.g., breaking away from the routine), enjoyable, child-like (e.g., non-serious), but also very serious as expressed in such artistic qualities as tension, beauty, harmony, and rhythm (Huizinga, 1950; Kosma, 2021).

To our knowledge, there is only one phronetic, quasi-experimental study supporting emphasis on performativity elements for improved health and the love of movement in aerial practice as dance and/or physical theater (Kosma et al., 2021a). Given also the link between phronesis and physical theater (e.g., bodily expression and sharing in phronetic action), the purpose of this interdisciplinary study was to examine the experiences of a physical theater class in relation to mental health, healthy lifestyles, play, and the love of movement among college students. Methodologically, the nature of the study is phronetic/hermeneutic phenomenology; thus, the emphasis is on the description of the students’ class experiences that can facilitate the development and implementation of enjoyable and meaningful physical activity programs for health and well-being within Kinesiology and performing arts.

Methods

Design and Procedures

This was a mixed-methods, phronetic and temporal study encompassing quantitative and qualitative data among seven undergraduate students, who enrolled in one semester-long undergraduate physical theater class at a major Southeastern university in the USA. The class was for credit, and it is part of the physical theater program in the university. It was taught twice/week, 1.5 hours each day by the Head of the Physical Theater program and an MS student, who is advanced in physical theater and aerial silks (performing aerial acrobatics while hanging from two pieces of fabric). Based on the holistic view of physical activity, the class content included physically demanding, playful, embodied, individual and group-based activities, such as dance and aerial dance, calisthenics, stage combat with swords, body posture and awareness, and bodily expression (Kosma, 2021, 2022, 2023; Kosma & Erickson, 2020a, 2020b; Kosma et al., 2021a, 2021b, 2023; Piggin, 2020). Key elements of the class encompassed skill development (e.g., individual, and socially interactive ways to express a story with or without equipment like aerial silks, stage swords, tables, stools, chairs) and performativity elements, such as creating choreography and physically performing via mainly bodily expressions. During the semester, students were expected to create etudes and perform formally (midterm and finals) and informally in front of their classmates. Performances were conducted individually or in groups. The class instructors were supportive and engaging, providing constructive feedback, and allowing the students to explore different movement variations on their own while learning also from each other.

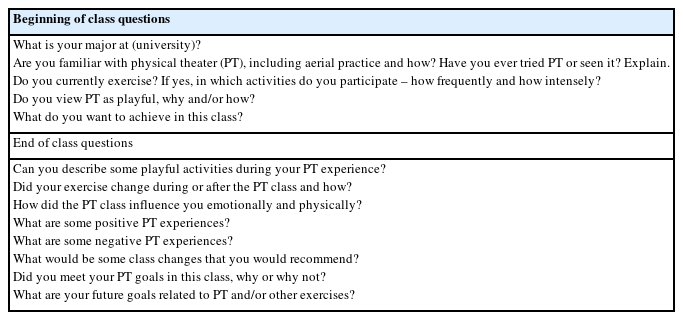

The first author, who was not the class instructor, conducted semi-structured individual interviews in her office to collect the study’s qualitative data. Interviews took place in the beginning of the physical theater class (first set of interviews) and towards the end of the semester (end of class – second set of interviews). Participants were first familiarized with the class by attending a few physical theater sessions prior to the first set of interviews. The length of the two sets of interviews varied: beginning of class: 11 minutes – 51 minutes; end of class: 13 minutes – 58 minutes. The Institutional Review Board of the authors’ university approved the study protocol prior to participants’ signing the study’s consent form. Study participation was voluntary, and the study participants could withdraw from the study at any time without any penalties. The interviewer (first study author) was not a class instructor and data anonymity and confidentiality were guaranteed. The content of the individual-based interview questions included college-based history of artistic expression, positive and negative physical theater class experiences, play in physical theater, class goals, and future participation in movement activities such as exercise and performing arts. See Table 1 for the content of the interview guide. The interview process was dialogical in nature to build trust and engage in in-depth discussions regarding the interview content from the beginning of the class until the end of the semester. Demographic information regarding participants’ age, gender, ethnicity, exercise participation, and education (e.g., major and minor) was also collected. All interviews were conducted in-person and audio-taped. The first author drafted the initial interview guide and discussed it with the study co-authors for clarity and consistency with the study objectives. The final questions were then pilot tested with two participants, whose results were included in the study.

Prior to the interviews, participants completed two standardized questionnaires regarding their depression and stress levels, encompassing the study’s quantitative data. Depression and stress were respectively measured using the 20-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale (CES-D) (Radloff, 1977) and the 10-item Cohen’s Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) (Cohen et al., 1983). Participants marked responses in the four-point (0–3) CES-D Likert scale indicating how they felt over the past week, whether depressed, happy, sad, fearful, without an appetite, etc. The range of scores on the CES-D scale is between 0 and 60, with higher scores indicating higher frequency of depressive symptoms. Four positive items were reverse scored for the analysis. The CES-D Scale has demonstrated acceptable reliability (e.g., α = .85–.90) and validity (e.g., discriminant and criterion validity) in a variety of populations, including African American, Caucasian, people of different education backgrounds, adolescents, and young adults (Radloff, 1977). Similarly, PSS is a five-point Likert scale regarding thoughts and feelings over the past month, such as depression, stress, anger, or being in control about life situations. The range of the PSS scores is between 0 and 40, with higher scores indicating higher frequency of stress levels. Four positive items were reverse scored for the analysis. The scale has exhibited acceptable internal consistency and factorial validity in a variety of populations, including adults and college students (Lee, 2012).

Data Analysis – Quantitative Data

Dependent t-tests were conducted using SPSS (V. 27) to examine potential differences in depression and stress levels based on time: from the beginning of the class until the end of the semester. Given the small sample size, Cohen’s d effect size (Cohen, 1988) for dependent t-test was also calculated.

Data Analysis – Qualitative Data

Audiotapes of the interviews were transcribed verbatim and double-checked for transcription accuracy. Participants’ actual names were replaced by pseudonyms for the purposes of reporting the study results. The interviewer, who was the first study author, entered the transcripts, post hoc reflections, and debriefing notes in the latest version of NVivo. The methodology used to analyze the study’s qualitative data was based on hermeneutic/phronetic phenomenology research, which encompasses several steps (Flyvbjerg, 2001, 2004; Kafle, 2011; Tuffour, 2017). The first author read the transcripts and notes multiple times to systematically code the data. Based on the coded data, she developed themes and categories by examining each individual story and the whole data set in a recursive process. The other study authors independently reviewed the coded data to finalize the themes and categories via consensus discussion. Representative extracts were then selected based on the coded data, the entire data set, study purpose, and the literature. A key element in the analytical process of hermeneutic phenomenology is the in-depth examination of a phenomenon. For this study, the authors were heavily involved with the studied subject via for example class participation and observation, democratic and informal discussions with each other and the participants (e.g., interviews), reflections of personal experiences, and use of recursive analytical procedures to attempt to capture the participants’ essence of their experiences. Importantly, this research is interpretive in nature by recognizing that different readers can give different meanings in the participants’ shared stories; thus, it is dynamic and open to change (Tuffour, 2017).

Results

Participant Characteristics

The study population included seven undergraduate students (Mage = 20.43 ± 1.28 years old; females = 6; males = 1; Whites/European Americans = 5; other [Hispanic or African American] = 2), of varied backgrounds in physical theater. Five students had taken one other physical theater class in college prior to this study’s class and one student had minored in physical theater prior to changing her minor. Nearly all participants were physically active (5 = regularly active; 2 = somewhat active). Most of them exercised at gyms while a few participants performed aerial silks and dancing (see Table 2 for participants’ exercise participation). Beyond performing arts (e.g., dance and physical theater), several students majored in a variety of programs, including Fine Arts, Communication Disorders, Film and TV Production, Psychology, Business, and Animal Science.

Differences in Depression and Stress by Time

Given the small sample size, Cohen’s d effect size – rather than statistical significance – is highlighted. The magnitude of Cohen’s d is interpreted as follows: small = .2; medium = .5; and large = .8 (Cohen, 1988). Based on the dependent t-test, there were no statistically significant differences in stress and depression over time. However, there was a nearly medium within-subject effect for stress levels (d for stress = .32, Mdifference = 3.5, η2 = 11%). In the beginning of the class, depression scores were lower than stress scores (Mdepression = 14.14; Mstress = 18.86 – scores of 20 are considered high stress; Cohen et al., 1983) and there was a tendency for scores to decrease over time with the highest reduction in stress levels (Mdepression = 13.14; Mstress = 15.42).

Emerging Themes

Based on the qualitative data analysis, three themes emerged. The first theme, positive physical theater experiences, was mainly expressed in the second set of interviews and included body confidence and comfort in expression, improved mental health and healthier lifestyle choices, continuing with performing arts in the future, and caring and supportive environment. The second theme, physical theater is play, emerged during both sets of interviews, highlighting the playful nature of physical theater (e.g., a non-purposeful activity that takes place outside ordinary life; fun, child-like but also serious; interactive). A few participants mentioned a couple of negative physical theater experiences (third theme), such as injury and darkness in theatrical expression.

Theme 1: Positive Physical Theater Experiences – End of Class

Body Confidence and Comfort in Expression and Creativity

Several students mentioned that the physical theater class helped them feel more confident and comfortable with their body. Cleo, who minors in dance, said that she met her class goal by “feeling more comfortable in this movement style.” Gabby, who is an aerialist and physical theater used to be her major, met her goals too by being more confident and explorative in her movement: “I am exploring my emotions a lot more and, overall, I feel more confident in my abilities. Maya (an aerialist), too, feels that physical theater challenged her and helped her grow and evolve:

“…feel more capable, more courageous to try new things, to do things that are uncomfortable… physical theatre has allowed me to embrace my personality, my physique, my intuition, and it’s challenged me in ways that I was not expecting… and I love a good challenge… And I’ve been non-stop growing… I even feel that the way that I speak is different. I feel that I’m just more confident in myself in conversation. If you would have met me my sophomore year this conversation would probably have been so different.”

Gretha (an aerialist) mentioned that she now feels more comfortable and confident with new ways of moving: “…I am more comfortable with more pedestrian ways of moving, not as dance like”… I am better at expressing through my body… it (class) made me think more creatively on my own, like more outside of the box.” Similarly, Kailin, who is also a dancer and would like to continue with physical theater in the future, highlighted the spontaneity in physical theater vs. technical perfection in dancing:

“I hope to continue taking Physical Theatre classes… how I would change dance, I think, and I even have done this, like bringing it to my classes that I teach at the studio, bringing aspects of “you don’t always have to know exactly what you’re doing.” Some will do improve in class in dance, which we’ve done before but it’s been very technical… telling the kids like, “You don’t always have to be perfect or like thinking exactly what you’re gonna do and then doing it. You can kind of be more spontaneous,” which I’ve learned a lot from Physical Theatre.”

Annie said that the class exposed her to “another way of thinking and expression… I’m kind of curious to learn a little more about it.” Irv capitalized on new ways of thinking, expressing, and creating by unlocking his body and mind in order to be spontaneous, immerse into his character, and become more flexible:

“…when it comes down to learning a new character, I like to get a feel for him, too. I want to introduce him to the things that I learned… I want him to be able to be as flexible as me and for him to be comfortable with his body as well… it allows me to play with my characters a little bit more and have fun with it. And I like how my body gestures can be used in a comedic relief when it needs to be, and I experienced that last week actually. I shot a short film where a character that I played – he was a goofy best friend, and I was able to find some good laughs by just throwing my body out there. You know, just being spontaneous with my body, which is something that Physical Theatre has unlocked for me… ‘Cause being able to unlock my mind and understand my body a little bit better, it’s allowed me to play with certain scenes and not be insecure about playing with those scenes… Sometimes there’s a way that you can rearrange your posture and really work with your posture and find a more powerful upset … Like you look like someone that’s good to talk to by simply opening your hand and standing straight and tall. Or you can slouch over and keep your head down and make it almost seem like you don’t want to talk to anyone. Like you’re shy. There are so many different ways that you can readjust your body and tell a whole story of yourself with your entire body. And that’s something I learned from Physical Theatre. .. it’s… really your… body language… you really learn to understand and tell a story with your body through Physical Theatre… and that’s what I love about it… I’m a storyteller. That’s what I do as an actor. I tell stories of my characters through my body. So, it’s important to me that I feel like I’m able to unlock every single movement possible so I have like a playlist to pick from.”

Improved Mental Health and Healthier Lifestyle Choices

Several students mentioned that the physical theater class improved their mental health. Cleo has social anxiety and depression and by expressing those emotions during her class performances it made her feel better:

“So, my mid-term was kind of depressing, a lot of the body functions were like shaking and fear, but after I felt like more calm because I’d gotten to express that. And so, it wasn’t in me anymore; it was more just like I got it out and so I was good… Emotionally I’d say I feel better throughout the day just ‘cause it might just be the movement of it and kind of like the camaraderie of the class. So, I’ll just feel better leaving school than I would days that I don’t have it (physical theater class).”

Gabby had also stress and anxiety during the semester due to school demands among other things. Participating in the physical theater class helped her with her mood and “those very low depressive states”:

“… I’ve got a very hard deadline coming up so at certain points there were things happening with that that caused a lot of anxiety at times, like depression… I guess my emotions throughout the semester have kind of been like a bell curve. So, it went down, and I had a very bad low around the middle of the semester… as most students do, because that’s a very stressful time. But as of the past few weeks it’s gotten a lot better. And granted, part of it I actually have been steadily going to class and making sure that I participate and go. So, it’s definitely been helping with my mood… whenever I would go to these classes in those very low, depressive states, I felt better coming out of it because it was therapeutic and cathartic that I could actually feel the emotions that I felt unconditionally and let it go through my body and see how it influences me, and at the end of the class I could just say “thank you” and let go of what I was feeling.”

The meditations in the beginning of the class made Gretha feel good throughout her day: “I love when we do the little meditation in the beginning ‘cause it feels like a nice break in my day. And then I don’t know, I feel like it sets me up to have a good day.” Similarly, in her first interview, Gretha mentioned that

“Physical theater is good for my mental health… even if I’m not feeling like going (to the class) I always leave, like, feeling better… you have to be open and vulnerable when you’re there, so I feel like I leave and I’m kind of just in a better state to not be as closed off throughout the day.”

Also, the physical theater class helped students stabilize, better sense/feel, and accept their emotions. Maya, who is typically a “happy and optimistic person”, managed to stabilize her emotions (“little ups and downs throughout the day”) due to the physical theater class. This class helped Gretha accept and sense/feel her emotions instead of “holding them in”:

“…it’s kind of helped me… sit in my emotions better. I don’t really cry often. I don’t like to cry very often, but I feel like… outside of the class, I’m more open to feeling my emotions… I feel like I just allow myself to feel them more… typically… in the past where I’d feel like I’m gonna cry, I’m just like, “Don’t. Don’t break down. Hold it in. Hold it together.” But now I kind of feel like I’m more okay with letting them be released.”

For some students, the physical theater class helped them improve their lifestyle by thinking and/or being more active and eating better. Cleo started thinking about being more active – thus feel better – due to the physical theater class:

“It definitely makes me want to be more active, because any day that we do something slightly active I feel better. I feel like I did something and so I should probably get back into doing stuff like that ‘cause it feels good. Like I was debating going to the gym last week. And I was like, “That’s new.”

Similarly, Gabby is more active and eats better due to the physical theater class. In this way, she also feels better and have more energy for her daily activities and class participation:

“…that class kind of influenced me to start wanting to be more active and, like, eat better. That, mixed with aerial, have kind of been doing that for me. Which as you probably know, is going to improve my mental state too… sometimes you get so busy that you can’t really cook for yourself. Like, you’re eating out more and as of late, I’ve been trying to meal plan and actually have good alternatives for myself at home, not only to save money, but to kind of get something a little better in me than what’s really readily available on campus. So yeah, I’ve been just trying to be more mindful about what I put in myself because I would notice going into aerial silks or into the Physical Theatre class, if I had not eaten or if I ate something very heavy, greasy, not the best for me, I felt very sluggish and sick going into class. And then having readily made meals that are kind of good for me more just nutrient-dense than other things, I felt a lot more energetic going to class. And rather than doing one activity full out, and then the rest of the class I’m just kind of like, “Ugh, I feel bad.” I’m able to actually go for longer and feel more involved in class.”

Continuing with Performing Arts in the Future

Several students expressed interest in continuing with physical theater and/or performing arts in the future because of enjoyment. Irv discovered physical theater last year (had taken another class with the same instructor) and he “fell in love with it”:

“…physical theatre is just something I love to do. I discovered it last year and I took the class with (instructor’s name) last year. And it was wonderful and then he introduced me to this opportunity to go to Edinburgh and perform in this summer’s festival and after that I really just fell in love with physical theatre. I might do for being a minor of mine. Definitely something I can put in the future ‘cause it’s extremely helpful to my areas and I never thought it would be. But I feel like that’s what so great about art. You can take random things and random knowledge and apply it to something else and collaborate it together and make it a whole original work.”

Kailin has always loved and prioritized performing arts, and this class validated her perspectives about physical theater and the field:

“I’ve always kept Performing Arts high on my priority list because it’s my passion, it’s what I want to do. So, it… (the class) has validated how I think about the arts and everything… I’ve enjoyed it so I’ll continue to put that as one of my priorities… I don’t think I’ll ever stop dancing.”

Cleo would love to continue with physical theater in the future as a hobby and perhaps learn how to incorporate aerial silks in her performances. Annie appreciated now physical theater more than before and she could “definitely pursuit it in the future again.” Similarly, Maya enjoyed the class; thus, “It’s definitely more in the forefront of my mind because I just enjoy it more every day and so I guess it takes up more space in my thoughts.”

Caring and Supportive Setting

The students felt that during their physical theater class they were in a very supportive and caring environment. Kailin enjoyed their “partner work” and coming up with a story for the midterm exam to share with her classmates. Cleo also spoke about this type of bonding:

“Whenever we were watching everyone’s midterms, I feel like we kind of like bonded. We were all just watching… We’d all say nice things, like we would give feedback. But I think the way that everyone handled it was just really kind and caring, and so that made me feel really nice that everyone was just truly trying to make each other better at it.”

Gretha also felt that she bonded with her classmates: “it was fun getting to know a lot of people in my class… I feel like with all this exercise that you do, they’re kind of weird, it like bonds you in a way.” Irv also spoke of a special type of bonding with his classmates, especially when in the very beginning of the class they had to perform activities outside their comfort zone:

“…you first enter the class and there was a whole bunch of random people, and he asks you to do some stuff that is completely out of your comfort zone and you’re not exactly going to be buzzed up, happy, and wanting to do it. This definitely takes a lot of guts and a lot of courage to process that and to be able to do that… It may be considered a con in the moment, but the connection that we were able to build with the ensemble and my peers is incredible. I never thought that I would have those connections with random people. Like I can really trust them, and they can trust me. And that’s a great environment to work in.”

Theme 2: Physical Theater Is Play – Beginning of Class

Non-Purposeful, Outside Ordinary Life

Students revealed that physical theater exercises are non-purposeful. Maya said that if “one tries too hard… worries about what other people see… or tries to make it too structured, then it is not playful anymore, it becomes something else.” Gabby mentioned that contrary to “adult, rigid, ordinary, and purposeful life,” physical theater allows one to express, explore, and be creative:

“Growing up and becoming an adult, I feel as though as we get older, we’re kind of supposed to be a little bit more rigid in what we do. There’s supposed to be purpose in every single move we make. And we’re not really allowed to have this creative kind of outburst like children get, so physical theatre kind of feels as though it’s allowing your body to express everything that it wants to express on a day-to-day basis that it’s not allowed to. It kind of feels like a kid in a sandbox. Everything’s still, everything’s leveled, but there’s still so much potential to what could be made.”

Similarly, Annie mentioned that contrary to “real life”, physical theater is playful and fun because there is no purpose in it and there is always an “element of surprise.”

“I think it – there’s always a fun note to it even when you were playing house as a kid and you were the mom and you were telling your kids to clean your room, it was something funny. Because you were just mimicking what you saw. But whether they clean their room or not, it didn’t matter. You just want that so there is play. There’s always an element of surprise, whereas with real life it can be a bit more black and white.”

One Giant Playground, Not Too Serious

Several students mentioned that physical theater is not too serious because it involves child-like, enjoyable, fun, unstructured activities, Irv mentioned that he would “not take physical theater too seriously, which is why I wouldn’t say it’s good for adults.” To him, it has been “one giant playground and I love it ‘cause I’ve been playing on a playground my whole life. An active imagination my whole life and now I get to have an active imagination for a grade in a class and possibly a profession in the future.” Gretha mentioned that although her friends find her physical theater exercises “awkward”, others in the class perform them as well: “everyone’s in the same position as you… You’re having to be vulnerable for any of the exercises that you do… It’s a lot of fun. I feel like you do get to play ‘cause nothing about it is too serious.” Cleo also mentioned that “to get the message across” the physical theater exercises can be child-like: “feels very charades-like almost, which, like, you play as a kid.”

Fun But Also Serious

Two students mentioned that physical theater is fun though at times it can be serious because of its artistic and dramatic form:

“…there’s, you know, it’s an art. So, it can be intense and serious or dramatic, but for the most part I find it playful cause that’s a lot of what I did as a kid. So, I associate running around on four legs as a cat, like, just having fun” (Annie).

“…it’s fun… it’s enjoyable… Sometimes you have to take it a little more seriously, like…having to come up with something to then show your peers. That gets a little bit more like… I’ve got to plan it out so that I can show my class and not, like, embarrass myself” (Kailin).

Theme 2: Physical Theater Is Play – End of Class

Interactive with Others or Using Props

Some students mentioned that their physical theater class is playful because are able to playfully interact with others or with props like stools, ladders, and chairs. In fact, several participants said that they would greatly benefit from additional partner work and use of prompts. Interacting with others or using props made physical theater more playful for Annie:

“It’s easier for me to interact with something and play… I remember the ladder was fun for me ‘cause I was like inside it, doing everything you’re told not to do with a ladder… like crawling the back side, crawling from like the inside, you know, crawling out through the rung. Got a little stuck, but that was fine. But I also think for me it’s easier to play with other people… we’re doing a group thing now and… one person in my group, she’s telling the story of her first date with her boyfriend, and then the boyfriend, and this other person’s a girlfriend, and then we have another person in our group… honestly, she’s the best character in the whole story because she’s everything else. But like we’re doing a car. We’re like, okay so we get in the car and we’re trying to make the scene a car and then finally she’s like, “I know. I can be the car.” And we’re like, “Oh, the console.” She’s like, “No, no, no. Like you should sit on me, like you know, riding horses.” But two people can’t really sit on her physically, so she like turns sideways and then we’re both sitting on her back and then she’s crawling like this way across the stage. And it’s just really funny… it’s unexpected, so it’s really funny. And then like both of us are like kind of scared to put our full weight on her, so we’re just like squatting but also walking forward. It looks really stupid, but it’s really funny. And I think yeah, that’s play.”

Kailin also said that “working with props in the class has been really fun… things like a trampoline, wooden boxes, a ladder, a stool, a chair, and we incorporate that into our movement, and it adds another element to story-telling because you have a prop to mess around with. But that’s been really fun,” For Gabriella, too, the class atmosphere is very playful because it is interactive and allows vulnerability:

“…So once meditation is over, we’re able to just focus solely on what we’re doing in class. And a lot of it’s been very playful. It’s been kind of us just interacting with each other and kind of making things up as we go, and I mean I’ve noticed quite a few times that I just kind of start laughing at myself. At first it was from embarrassment, like, “Oh, I feel like I look so stupid.” And now it’s more kind of like, you know whenever sometimes an atmosphere happens and it just makes you laugh. Like, you’ll look at someone and nothing funny is happening. You don’t think the other person looks stupid, they don’t think you look stupid but you’re just kind of like, “Cool.” Just laughing at everything. That’s kind of how the atmosphere’s been, very playful, very interactive with others and a lot more vulnerable in a good way.”

Child-Like, No Childish

Maya and Cleo capitalized on how physical theater reminded them of their childhood and child-like play.

“We did one thing in class where it was like one person wasn’t looking and the other was guiding them around the room and that just kind of reminded me of childhood and playing, so that felt very playful” (Cleo).

“I’m always keeping in mind is to never lose our sense of child, like to be child-like. I think that that’s so valuable… not childish, child-like. Because there’s a beauty in children. They do not worry; they are not bound by any thoughts or comparisons. They just are. They just exist and they, you know, say what they want, and they play, and they don’t care. And there’s a beauty in that and I think that no one should ever lose their child-like sense. And I think that physical theatre… encourages you to be child-like. Because as a child would, you wouldn’t be worried about anything else… you don’t even think about it, you’re just moving. You’re just playing. There’s a chair there, you’re gonna climb on it. You’re gonna try and flip on it… and that’s what we do in class. So, I guess that’s why I would describe it as playful” (Maya).

No Purpose, No Pressure, Outside Ordinary Life

For Gretha physical theater is playful because she is performing activities that she does not usually perform in her ordinary life. For example, one time the lass instructor asked her:

“…to move like your eyebrows are controlling you.” And… that is so weird, but it was fun. I ended up doing stuff that I like normally would not do at all. So, I feel like it’s playful in a sense. It’s just like outside of the box and it’s not stuff that I would necessarily think to do on my own if not prompted.”

When Irv realized that there are no “masterpieces” in physical theater and he was able to relax and listen to his body, he mostly enjoyed it, found it playful, and learned.

“…there’s no masterpiece, when you have no pressure on you, you can really just relax and see what your body does. And to me that feels like play. That’s what I did when I was a kid. You play to make pretend. You didn’t pay attention to nobody else. I mean you just went about your day. You did whatever you felt like you could do. And that’s what I feel in Physical Theatre. I do whatever my body feels like it’s capable of doing. And he helps you also not only to see your capabilities but push the limitations. And I’ve noticed that a lot. In ensembles it can be challenging sometimes, like today in class I had a whole girl put an entire weight on my one leg, and actually if I would have had the pressure of thinking, “Oh it has to be perfect” or “well I have to do this to the correct format… you’re not doing it correctly, you need to do it like this”… then it would have been a lot harder to achieve some of these things that we’ve done in the class. I feel like seeing it as play is the best way to see it in my opinion because that’s the best way for me to learn.

Theme 3: Negative Physical Theater Experiences – End of Class

Injury or Having a Bad Day

Maya’s only negative experience with the class is when she is tired or has a bad day and she still needs to “move around” and perform all class activities. However, “being allowed to express that is nice.” Annie felt bad when one of her classmates was injured in the class, though she was not responsible for the injury. During a partner activity, Irv felt “terrible” when his partner got hurt. He had already had a bad day and this injury “definitely did not help out”:

“…we were doing some more challenging partner work and… technically it wasn’t my fault, but I hurt a girl’s leg. I was standing on both her legs and her leg gave out and she hurt her knee. And I felt terrible about it, like I’d already been having a pretty bad day. I’m not gonna lie to you. It felt like things just weren’t going my way and I couldn’t cope at that exact moment. And then, right then and there, boom. The girl hurts her leg, and you know, that definitely… didn’t help the day feel any better and I was feeling really down about it for quite a while, but (instructor’s name) helped me to see that accidents happen… it’s all a part of the work. But I would say that’s something negative to think about that you have to realize that you’re really putting your body at risk. And yeah, it’s fun and it’s play, but you can also get seriously hurt.”

Performance Anxiety and Darkness in Expression

Gabriella spoke of performance anxiety in physical theater and how at times it is challenging to perform without any “emotional anxiety”:

“I think with any kind of performance there’s always that anxiety of “will people like my piece? Will people like me?” And obviously as the semester’s gone on, it has lessened a lot because we’re very open with each other in class and I mean, nine times out of 10 someone’s gonna have something positive to say and that 10th time is just gonna be (instructor’s name) with a very small critique on how you could do it better. So, it’s not really negative experiences from the class itself, it’s more just kind of getting used to performing unconditionally with no emotional anxiety or tie to it… Every performer kind of has that anxiety. It never fully goes away. It just becomes more back of the mind thought than front of the mind thought.”

Maya prefers to “express something positive” in physical theater; however, she has noticed that there is also “a lot of negativity and negativity in expression”:

“…I really prefer to express something positive than something negative just because… I’ve seen so much negativity in theatre… a lot of times there can just be a lot of darkness or maybe a lot of hurt or things like that that people are allowed to express in theatre, and I think that’s why you just see it more. And again, like I said, I’m a happy person so… I much rather prefer to express something positive.”

Discussion

The purpose of this mixed-methods, phronetic and temporal study was to examine the experiences of a semester-long physical theater class in relation to mental health, healthy lifestyles, play, and the love of movement among active college students. Study results will be discussed starting with the quantitative data and theme one and continuing with the other two emerging themes of the qualitative data.

Quantitative Results and Theme 1 – Positive Physical Theater Experiences

Based on the dependent t-test, there were no temporal statistically significant differences in stress and depression; however, there was a tendency for both variables to decrease over time with a nearly medium within-subject effect for stress levels. This tendency is further strengthened by the qualitative results, whereby the students mentioned that their mental health, like symptoms of depression and stress, significantly improved due to the physical theater class. Students were able to stabilize and express their emotions in a healing and cathartic way; thus, positively impacting their daily activities. It is shown that movement experiences in performing arts like dancing and aerial dancing – with emphasis on performativity – can lead to improved mental health and decreased stress and depression (Koch et al., 2014; Kosma & Erickson, 2020a; Kosma et al., 2021a; López-Rodríguez et al., 2017). Linked to this study outcome is the finding that participants gained body confidence and comfort in exploring and expressing this “new movement style” in physical theater via bodily storytelling. In this way, they were able to better immerse themselves into their character, express their emotions, and feel better. There are only a few empirical studies in performing arts that have showcased the embodied nature of dancing and aerial dancing (e.g., Kosma & Erickson, 2020a, 2020b; Kosma et al., 2021b). The scarcity of such types of research in physical theater has already been acknowledged (Blair, 2019).

Another unique finding in this study is the link between physical theater and healthy lifestyles like increased exercise levels and healthy diet. Also, study participants enjoyed their physical theater experiences, including elements of performativity, embodied expression, mental health, and partner work within a caring and supportive environment; thus, they stated that they were planning on pursuing performing arts in the future either as physical theater or dance. In another study among aerialists, it was shown that performative and expressive movement experiences within a supportive and highly interactive setting link to healthy lifestyles and the love of movement in the future (Kosma et al., 2021a). Aerialists can form strong communities to share their passion and keep on learning and evolving (Kosma & Erickson, 2020a; Kosma et al., 2021a, 2021b). Viewing physical theater as an end in itself and falling in love with it for its sheer joy and the integral experiences it can afford is phronetic in nature – a virtuous act to lead the good life and sense well-being (Aristotle, 350 BCE/1962; Kosma & Erickson, 2020a, 2020b; Kosma et al., 2021a, 2021b; MacIntyre, 2015).

Theme 2: Physical Theater Is Play – Both Sets of Interviews

Another unique finding that further supports the phronetic nature of physical theater is that study participants viewed their class experiences as playful, encompassing such elements as “a giant playground”; a relief from the routine; a non-purposeful, child-like fun activity which can also be very serious; an interactive expression via social communication (e.g., partner work) or use of props. In his magnum opus, Homo Ludens, Huizinga showcased the link between performing arts and play, in that play has such artistic qualities as tension (unpredictable outcome and a virtuous act), beauty, harmony, and rhythm (Huizinga, 1950; Kosma, 2021). As described by Huizinga and supported in this study, the key elements of play are part of physical theater: a non-purposeful, child-like activity that can also be very serious (e.g., creating a theatrical piece and sharing a story with others); a relief from the routine because it takes place outside ordinary life; a social activity with others or objects; an artistic expression that leads to good life (Huizinga, 1950; Kosma, 2021; MacIntyre, 2015; Rodriguez, 2006). In his work of art Truth and Method, Hans-Georg Gadamer (1975/2012) showcased that artistic expression is play, in that play’s essence and significance relies on the experience it can afford and cannot be objectified – it has no purpose; it is done for its own sake. Play is orderly, and its unique nature – to-and-fro movement – attracts the player. “What holds the player in its (game’s) spell, draws him into play, and keeps him there is the game itself” (Gadamer, 1975/2012, p. 106). Playful, artistic activities like dancing and aerial dancing are shown to be enjoyable for life (Kosma & Erickson, 2020a, 2020b; Kosma et al., 2021a, 2021b).

Theme 3: Negative Physical Theater Experiences

According to Theme 3, only a few participants expressed some negative class experiences, including injuries of their classmates, having a bad day unrelated to class, performance anxiety, and negativity in theatrical expression. However, they did mention that those experiences are part of the physical theater process, such as “accidents happen” and “a lot of darkness… that people are allowed to express in theater.” Reports of injuries, having a bad day, and mental blockages because of slow progress in aerial silks have been also found in other studies (Kosma & Erickson, 2020a; Kosma et al., 2021a). Concepts of performance anxiety and darkness in theatrical expression are unique in this study, likely because of its performative nature. As the participants revealed, expressing negative feelings and anxiety can be healing and cathartic, which may be one of the reasons for the positive link between physical theater and mental health.

Limitations and Future Directions

Although there were no statistically significant differences in depression and stress over time – perhaps due to the small sample size and the lack of depth in standardized assessments – a nearly medium effect size was found for stress and there was a tendency for both variables to decrease over time. The qualitative data did capture the strong link between physical theater and mental health. The goal of qualitative studies is not to generalize findings; yet study generalizations can take place even with one participant (Flyvbjerg, 2001). It may not be possible to generalize the findings to large populations, but the results can generalize to relevant groups like active college students with stress and depressive symptoms. Future studies should examine physical theater experiences among different people like clinical populations, adolescents, and older adults.

Conclusion and Implications

To our knowledge, this was the first mixed-methods, temporal and phronetic study on physical theater experiences regarding mental health, lifestyles, play, and the love of movement. Instead of relying exclusively on standardized assessments for mental health, a qualitative in-depth analysis offered rich and meaningful results in the study subject. Participants enjoyed the physical theater class by experiencing body confidence and comfort in expression and creativity, positive emotions, and improved lifestyle choices within a supportive and caring community. They viewed physical theater as a playful and immensely enjoyable activity, which they wanted to pursue in the future. Their negative experiences were limited, including injury and having a bad day, performance anxiety, and darkness in theatrical expression, Given the rapid and vast decline in mental health among young adults, especially due to Covid 19 (Kosma et al., in press), movement educators within Kinesiology and performing arts can offer ways to reverse this situation and improve the quality of life and well-being of college students. In Kinesiology, physical theater, and dance settings, practitioners should emphasize physically demanding, safe, bodily, creative, and playful activities within a supportive and community-oriented environment. Expressing negative feelings should not be discouraged because it can be healing and cathartic. Positive movement experiences in Kinesiology and performing arts can lead to the love of movement for a lifetime.