Analyzing the Voice of Recipients of CSR Activities from #NBATogether Campaign: Analyzing Twitter Posts and Comments through Critical Discourse Analysis Lens

Article information

Abstract

This study aimed to analyze the voice of recipients of professional sports teams’ corporate social responsibility (CSR) activities. Fairclough’s critical discourse analysis (CDA) was adopted and analyzed 275 tweets from every NBA team that included the #NBATogether hashtag from March 20th to April 20th, 2020. Results suggested the public mostly complied with discourses created by NBA teams, but challenging discourses were constantly created in comments. This study provided possible reasons to support these findings. First, the conceptual background of CDA is provided to justify the creation of different discourses in comments. Second, the characteristic backgrounds of users following professional sports teams’ social media were mentioned as a possible cause of complying discourse as dominant in comments. Third, the research also highlighted how social media should not be a panacea for delivering CSR discourse, which brings up the necessity for the traditional media to be considered as not all public have internet access. Finally, the importance of analyzing the public’s discourse was mentioned to emphasize the benefits of both professional teams and communities.

Introduction

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) activities, such as community engagement and volunteer work, have been gaining attention in sports management academia for their merits in the sports industry (Walker & Kent, 2009). Walker and Kent (2009) pointed out specifically that one of the unique features of CSR in sports is the star power that helps professional teams to acquire high visibility through their top players. Consequently, high-profile professional sports teams tend to have close connections with their local community by utilizing CSR activities (Stoldt et al., 2012). Public audiences expect professional sports teams to give back to their community through CSR activities as the public regards professional sports teams as beneficiaries of many advantages from the local community: such as using tax money to build new stadiums or being exempt from antitrust, etc. (Babiak & Wolfe, 2009). Hence, Stoldt and his colleagues (2012) regarded the importance of professional sports teams’ CSR activities as paramount, stating, “Given the combination of visibility, strong community connections, and high expectations among the public, CSR is probably more important for sport organizations than it is for other entities.” (p. 235).

Noting the importance of professional sports teams’ CSR activities, the National Basketball Association (NBA), one of the high-profile professional sports leagues in the world, established ‘NBA Cares’ in 2005 as their CSR specialized program. NBA Cares stated in their mission that “NBA Cares is the league’s global social responsibility program that builds on the NBA’s mission of addressing important social issues in the U.S. and around the world” (NBA Cares, n.d.). In alignment with this mission, NBA Cares utilized its social media to promote the ‘#NBATogether’ campaign during the global coronavirus pandemic, stating, “Introducing #NBATogether, a global community and social engagement campaign that aims to support, engage, educate and inspire youth, families, and fans in response to the coronavirus pandemic” (NBA Cares, 2020). In response to the NBA Cares campaign, various NBA teams and players utilized their Twitter platforms to promote their CSR activities, such as donating meals or budgets to local communities in difficult situations due to coronavirus, promoting awareness of the seriousness of the virus, and other community engagement efforts. NBA Cares’ active utilization of social media is one of the ideal examples of how social media are used in risk and crisis communication (Rasmussen & Ihlen, 2017).

However, Rasmussen and Ihlen (2017) mention in their study that, “Nevertheless, empirical studies show strong patterns of homophily in social media, in that elites follow elites whereas “ordinary” citizens rarely get attention” (p. 2). In sports management academia also, while various previous research mentioned the benefits to professional sports teams in terms of organizing CSR activities, such as enhancing the positive image of initiators, promoting interest and participation in games or products, developing local communities (Babiak & Trendafilova, 2011; Babiak & Wolfe, 2006; Stoldt et al., 2012; Irwin et al., 2008; Walker & Kent, 2009), studies that show how citizens react to these CSR activities are lacking. Although studies in sports management academia utilize CSR-related surveys to hear public opinions toward professional sports teams’ CSR activities, voices of the public are used in academia to represent how beneficial the CSR activities are to organizers, not to demonstrate recipients’ opinions in detail. Previous research also mentioned that while most sports media articles demonstrate how professional baseball teams actively participate in CSR activities, almost none mentioned actual CSR recipients’ voices and experiences (Kim et al., 2018).

In this aspect, the purpose of this study is to fill in the research gap by analyzing and comparing both NBA’s and public’s voices regarding the #NBATogether campaign through Twitter posts and comments. Through this process, this study aims to determine if both parties’ posts and comments contribute to the creation of certain phenomena or social changes by sharing and reacting to #NBATogether CSR activities. As a result, this study seeks to act as a foundational study on both giving attention to the public’s voices in social media and discovering any difference in both party’s voices. Therefore, to analyze and compare the voices of the two parties through the #NBATogether campaign on Twitter, the following research questions were developed:

RQ1) What kind of vocabularies are used when describing the NBA’s CSR activities in Twitter, specifically with #NBATogether?

RQ2) Does the usage of vocabularies differ between original posts and comments in NBA’s CSR activity tweets?

RQ3) Do discourses formed between NBA’s CSR activity Twitter post contents and comments written by the public differ from each other?

Literature Review

Corporate’s Social Responsibility (CSR) in Sport Studies

The foundational notion of CSR can be defined as obligations that corporates have towards the community. Many previous studies mentioned that as corporates need to receive benefits from communities to operate, corporates have their social duties to give back to their communities, and these actions of giving back for social development is defined as CSR (Davis & Frederick, 1984; Frederick, 1998; Maier, 1993). In this aspect, Khandelwal and Mohendra (2010) explained CSR as “what business puts back-and can show it puts back-in return for the benefits it receives from the society” (p.21). Although there are many ideas on defining CSR in academia, McWilliams and Siegel (2000) mention in their study that the generally accepted definition of CSR is a representative of actions that aims to foster social development but are not forced by law while expanding the interest of corporate as beyond financial.

CSR activities were actively connected with sports organizations also. While CSR was not a common concept in the 1990s, Babiak and Wolfe (2006) stressed in their study how professional sports organizations started to be rapidly involved in CSR activities starting in the mid-2000s. In order to use sport as a vehicle to initiate CSR activities, Smith and Westerbeek (2007) mentioned that a clear definition of what sports organizations’ social responsibilities are in their community need to be provided. Walker and Kent (2009) emphasized the difference of CSR in sports industries as, “the sport industry CSR differs from other contexts as this industry possesses many attributes distinct from those found in other business segments” (p.746). Special characteristics of CSR activities in sports organizations were pointed out by Smith and Westerbeek (2007) as: “Rules of fair play, safety of participants and spectators, independence of playing outcomes, transparency of governance, pathways for playing, community relations policies, health and activity foundation, principles of environmental protection and sustainability, developmental focus of participants, and qualified and/or accredited coaching.” (p. 47–48).

Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) in Sports Media Studies

According to Foucault (1972), who theoretically established the term discourse, discourse is defined as a general domain of speech and sometimes a set of speakers that can be individualized or a formal practice that can explain the speeches. Fiske (1994) further explained discourse analysis as a process of relocating the meanings made from the abstracted structural system into specific social, historical, and political systems. Discourse, then, is always socially and culturally located, politicized, and power-bearing (Fiske, 1994). Furthermore, Fairclough and Wodak (1997) proposed that discourse can help produce and reproduce power relations by portraying exemplary or deplorable figures. In other words, discourse contributes to making a specific phenomenon of society and can lead to the change of power status in society. Fairclough (2013), in his later work, mentioned that CDA aims to provide interpretations and explanations in various areas of social lives by identifying the cause of social wrongs and producing knowledge that can contribute to fixing those social wrongs.

CDA was utilized in sports media studies on various topics. Specifically, race (Lavelle, 2011; Simon-Maeda, 2013) and gender (Wolter, 2015) issues were explored in previous studies by utilizing CDA processes. For example, Simon-Maeda (2013) stressed how media strengthens cultural stereotypes, which are primarily based on ideologies of race and nationality, by utilizing published articles that highlighted Daisuke Matsuzaka, a previous Japanese Major League Baseball player. Similarly, Lavelle’s (2011) study utilized commentaries from NBA games to analyze if commentaries contribute to building Black masculinity. The study concluded that the commentaries did not contribute to building Black masculinity images as the commentators strived to keep the positive image of the league and avoided portraying negative images of players. Wolter’s (2015) study emphasized how articles in espnW use words to exhibit the power and privilege of male players. For example, the study provided examples of how female athletes are described as more emotional in sports media articles, how non-sport-related issues are often being centered in their articles, and that their physical/personal characteristics are emphasized in related articles (Wolter, 2015).

Social Media in Sports Media Studies

According to Williams and Chinn (2010), social media can be defined as “tools, platforms, and applications that enable consumers to connect, communicate, and collaborate with others” (p.422). Meng and colleagues (2015) mentioned how social media is beneficial to sports organizations, managers, and marketers, as this media platform provides numerous opportunities. More specifically, the most valuable aspect of social media platforms is that social media enables fans to engage in the new and mutual experience with their preferred teams, and this experience develops relationships between fans and sports organizations. This relationship is mentioned to have the potential to be beneficial to sports organizations when considering the market’s competitiveness (Meng et al., 2015).

Moreover, social media platform is being emphasized more in the sports industry, considering how previously mentioned advantages are utilized. For example, sports organizations, athletes, sponsors of sports organizations and athletes, and media platforms utilize social media to communicate and deliver information to consumers (Mahan, 2011). Abeza and colleagues’ (2017) study also mentioned how Twitter is beneficial in empowering relationship marketing for sports organizations. Since the social media platform provides opportunities for fans to engage in communications with their following teams or players, this strengthens the fans’ feelings of bonding with the teams they follow. Furthermore, as there is no extra cost on posting articles on social media, this platform enables sports organizations to develop relationship marketing strategies that are more “practical, affordable, and meaningful” (Abeza et al., 2017: 353).

Social Media in Times of Crisis

Crisis can be defined as situations when commonly shared values are exposed to an immediate threat, which consequently affects various actions to be noticed from the public, such as: demanding a prompt reaction from the government, having uncertainties about the history and expected result of the situation, finally, what the future solution will be to solve the situation (Boin et al., 2005). Previous studies emphasized how social media usage increases during a crisis (Sweetser & Metzgar, 2007) and how Twitter is suitable during a crisis as it is often used for short and quick updates (Schultz et al., 2011). Usage of social media during a crisis is also discovered in previous studies as of retrieving information (Jin et al., 2014), keeping in contact with families and friends (Procopio & Procopio, 2007), relieving stress by looking at content with humor (Liu et al., 2013). Not only that, according to Kapoor and colleagues’ (2018) review of social media studies in information system journals, a relatively emerging theme of the field showed how some users utilize their social network to seek help and support during a crisis. Social media is also said to contribute to society by providing various ways of empowerment that lead to collective control and participation (Meng et al., 2015). Strategies of utilizing social media during the crisis were also dealt with in the previous study that messages from leaders of the organization showed more effectiveness than messages sent from an organization (Snoeijers et al., 2014). In this line of thought, another way to deliver messages to the public in a crisis was mentioned as utilizing personal voice or story form, rather than the official address of the organization, since personal voice or story develop interactivity with the public (Park & Cameron, 2014).

Methods

Data Collection

This study chose critical discourse analysis (CDA) to analyze and compare discourses derived from Twitter posts and comments with the #NBATogether hashtag. Twitter posts and comments that had the #NBATogether hashtag from every NBA team’s Twitter page from March 20th to April 20th were collected; March 20th was when the #NBATogether campaign was initiated, and data were collected for data one month period. The time period for data collection was based on the authors’ consensual agreement that this length of time will be when the NBA teams are most active with their CSR activities due to the temporary closure of the season (March 11th – July 30th, 2020) and the initiation of the NBATogether campaign (March 20th).

Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA)

According to Kivunja and Kuyini (2017), the critical/transformative paradigm focuses on discovering social injustice in context and provides a channel for those with relatively less power to make their voice heard. This qualitative paradigm aims to promote understanding of problems and induce social change for individuals and their culture, rather than looking for an absolute truth that can be broadly generalized. Moreover, previous research has mentioned not only how critical theory perspectives are dealing with empowering people who are constrained by their race, class, and gender, but also how researchers utilizing critical theory should be aware of their power; not limited to when engaging in dialogues but also when utilizing the critical theory to interpret or illustrate societal action as well (Fay, 1987; Madison, 2011).

According to Mills (1997), Fairclough sought to uncover the relationship between the discourses and societal changes, focusing on primary relationships between the context of discourses and social phenomena that are produced and delivered through the media. Through discourse research, Fairclough observed that social subjects are involved when discourses are formed and that discourses are dependent on each other. Fairclough (2013) mentioned that critical discourse analysis (CDA) aims to provide interpretations and explanations in various areas of social lives by identifying the cause of social wrongs and producing knowledge that can contribute to fixing those social wrongs. Another explanation regarding CDA was mentioned by Van Dijk (1993), stating that CDA researchers’ focus on dominance and inequality within society makes CDA different than other discourse analysis approaches, which have a heavier focus on contributing to a particular discipline, program, education, or discourse theory. Hence, it is noted that CDA is more of a transdisciplinary approach that is free from concrete distinctions amongst theory, description, and application.

Procedure

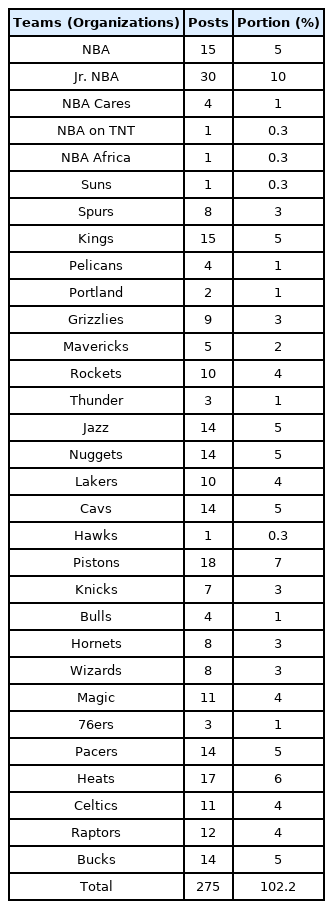

CDA presents the discourse in three frameworks: textual, discursive, and social practice. In order to analyze each of these three dimensions, Fairclough proposed to reveal the characteristics of the text, identify the relationship between the social phenomenon in the discourse and the text within the discourse, and finally, the connection between the practice of discourse and socio-cultural background (Fairclough, 1992, 1995, 2003). As a result, a codebook was created with 275 tweets from 30 NBA teams and NBA-affiliated organizations, such as NBA, NBA Jr., NBA Cares, NBA on TNT, and NBA Africa. Comments in 275 tweets were collected, excluding comments that only had emoji and memes. Then, a codebook was shared with coauthors to reach a consensual agreement on both the research procedure and the result of the codebook. During this process, triangulation with coauthors was done to secure the study’s credibility (Miles & Huberman, 1994).

Results

In response to the global pandemic, NBA and its affiliated organizations utilized their Twitter account to promote their participation in the #NBATogether campaign. Table 1 shows the number of tweets included and their portion in this study.

Analyzing the Vocabularies Used in Original Posts and Comments

After analyzing original posts and comments from tweets that included the #NBATogether hashtag, words such as “thank” (n=101), “stay home” (n=76), “love” (n=67), “help” (n=48), and “community” (n=37), were found to be the five words that were used most often. Moreover, hashtags such as #actsofcaring (n=40), #inthistogether (n=32) were also found repeatedly in posts and comments. “Thank” was used mostly in both tweets from NBA-affiliated organizations and comments from the public. NBA teams tweeted, “We are thankful for the bravery and dedication of our healthcare workers fighting on the frontline against #COVID19 #NBATogether | #ActsOfCaring” and “For #WorldHealthDay we would like to thank the nurses, doctors, and healthcare workers on the frontline fighting #COVID19! We can’t wait to get back to moments like this!” The public also tweeted, saying, “Thank you guys for posting these is really helping me while I’m in quarantine” and “Thanks for including us! All #InThisTogether is RIGHT!” “Love” was almost only used by the public in comments, appeared only four times in original posts out of 67 references that the word ‘love’ was included in either original posts or comments: NBA teams twitted, “The Pistons send our thoughts, love, and appreciation to our #HealthcareHeroes at @HenryFordNews and all over the country on #NationalDoctorDay. #NBATogether #ActsOfCaring”, while the public tweeted “Love you guys and miss y’all,” “Yes Wendell! I always love to see you being a positive role model for not only our youth but everyone!” and “Love this! Keep it going coach!”

Moreover, our study was able to find differences in subject pronoun usage between original posts and comments. While NBA-affiliated teams wrote original posts to pass on information, market their events or products, or acknowledge certain subjects’ hard work on overcoming the pandemic, the public wrote comments in original posts that mostly complemented the deeds done by NBA affiliated organizations. As a result, pronouns such as “you” or directly mentioning someone’s Twitter account were commonly found in NBA-affiliated organizations’ original posts. In contrast, words such as ‘guys’ or first-person pronouns were used commonly in comments written by the public. Examples of NBA teams’ posts were, “Today in his home town of Fayetteville, @Dennis1SmithJr purchased food vouchers for 575 First Responders from the Cape Fear Valley Medical Center. #NBATogether #ActsOfCaring”, while publics wrote, “Thank you guys! I don’t enjoy working under these circumstances, but I gotta do what I gotta do”, “My guy!!!”, “Great article @tugs_ @tugs20 stay healthy and safe to you all you guys”.

Analyzing the Discourses Formed Between Original Posts and Comments

According to the CDA, the original procedure should first analyze the differences in the discourses formed in social media and then investigate what socio-cultural backgrounds formed those discourses. Yet, since the socio-cultural situation that affected the discourses this study is striving to investigate is so evident, the global COVID-19 pandemic, this study focused on analyzing the differences in discourses formed between two parties: the teams or related organizations, and the public. Based on the findings of differences in usage of vocabularies between original posts and comments, this study was able to find there were differences in discourses formed in original posts and comments. Especially in comments, while discourses that supported original posts seemed dominant, counter-discourses against original posts could also be found. Original posts written by NBA-affiliated organizations focused on forming discourses to support their fans through the pandemic. For example, original posts provided basketball drills or recreation materials that can be utilized during quarantine, shared news about star players in certain teams donating items to communities, and communicated with fans by answering questions received through Twitter. Specifically, similar tweets such as, “Grizzlies player @j_josh11 takes you thru his stretching routine. His areas of focus for optimal performance? Hamstrings, quads, glutes, hips. Take it from the pro: do these daily to improve your biomechanics and overall flexibility! @memgrizz @jrnba #JrNBAatHome #NBATogether”, or “@sdotcurry continues to set an example! Raising hands Last week he paid for lunch & dinner for @Parkland ICU from @canerosso & Uncle Ubers. Keep supporting those local businesses during this time! #MavsSupportLocal #NBATogether” were often found in original posts with #NBATogether.

However, while most of the comments were forming discourses to support and comply with the original discourses formed by NBA-affiliated organizations, our study was able to find counter-discourses against original discourse in comments written by the public. Dominant discourses formed in comments were appraisal or appreciation of NBA teams’ information, messages, or recreational tools. For instance, the majority of fans wrote comments to support the tweets that are posted by teams they follow, such as, “Thank you for your kind words!”, “Thank you @Dennis1SmithJr for remembering your hometown heroes. We appreciate you #fayettevillenc #GoPack”, and, “Yes Wendell! I always love to see you being a positive role model for not only our youth but everyone!” Yet, not dominant but constantly, comments that disagree with the content of the posts were found and seemed to form counter-discourse against the original post. For example, comments such as, “what about people with neighbors downstairs?”, “you are such a good dude.....but how are the downstairs neighbors handling the dribbling drills?”, “I wonder how your neighbors below you feel right now,” and “but momma gonna get mad for “running up and down them steps” were written in basketball drill video tweets posted by NBA teams. Moreover, some public responded with comments such as, “Go to poor neighborhoods and pay for people’s / families groceries! ACTION needed not PR.......”, and “Don’t get me wrong it’s a nice gesture that these athletes are making these videos. But they aren’t the ones who are going to struggle financially. Why not go help people with action vs. a feel good video,” in Twitter posts with an encouragement message video. Hence, while NBA teams formed supportive discourses towards community, not all publics complied with NBA teams’ discourses, but some formed challenging discourses insisting NBA teams should think of community’s situation more carefully and get into actions than posting videos.

Discussion

Discussion of the Results

The difference in vocabulary usage in posts and comments written by NBA-affiliated organizations and the public is supported by a previous study. Meng and colleagues (2015) mentioned in their study that there are four types of communication in social media: sharing information, marketing, activation, and personalization. Based on this notion and according to our findings, while the NBA affiliated organizations wrote posts intending to share information or market their virtual events that can activate fan’s participation, the majority of the comments written by the public centered on the intention of personalization, in other words, showing their support towards their teams or players.

The characteristics of the CDA process support differences in discourses found through the CDA process in this study. CDA utilizes the usage of languages to analyze the differences in power between social groups by praising or neglecting certain ideologies when ideologies act as a certain group’s basis of practices and discourses (Fairclough, 1995; Simon-Maeda, 2013). Hence, the differences in vocabulary usage in the two parties found in our study through the CDA process reflect that power relation in discourses formed by NBA-affiliated organizations and the public is not always the same. While most of the public followed original discourse by praising the good deeds mentioned in original tweets, original discourses were constantly challenged in comments by the public, showing disagreement and forming counter-discourse.

Van Dijk (2003, 2008) also mentioned that the key aspects of CDA are whether a certain party is controlling to form specific discourse or does discourse control a certain party. According to our study, CSR discourses found in #NBATogether tweets and comments did not seem to be controlled by certain parties or control-related parties. As mentioned above, although discourse formed by the NBA seemed to be supported dominantly by the public who wrote comments, counter-discourse was noticeable that prevented control of discourse by certain parties and prevented certain discourse from controlling both parties included in tweets. Lack of counter-discourse can be explained by the previous study result that not all public facing the pandemic have access to online (Rasmussen & Ihlen, 2017), and fans active in SNS are mostly those who are passionate followers of the teams they are in favor of (Funk & James, 2001; Vale & Fernandes, 2018). As the population using Twitter is more likely to be biased towards team-friendly, this tendency of lack of counter-discourse of NBA affiliated organizations’ CSR discourses seems hard to avoid. Therefore, social media should not be a panacea for delivering CSR discourses to receive various public voices but should consider utilizing both social and traditional media (Kent, 2010; Kent et al., 2013). More specifically, paying attention to the public’s voice more in different forms of media than social media will help professional sports teams to notice if there are counter-discourses formed by the public regarding their CSR programs and find the necessity if their CSR programs need to be revised to meet the needs raised by different discourses of the public.

Limitations

This study’s limitation lies in the limited resource of data collected for this study. This study only collected specific professional sports leagues’ tweets with hashtags to analyze differences in two stakeholders’ discourses. This study also collected tweets in a one-month period, while discourse can change in the later time period since online discourses are changed often and quickly (Thurlow & Mroczek, 2013). Another limitation in data collection is that this study only utilized tweets as a source of data, while previous research indicated how Facebook and Blogs were also frequently used in risk and crisis studies focusing on social media (Rasmussen & Ihlen, 2017).

Future Directions

Our limitations bring future research opportunities when analyzing CSR discourses in professional sports teams’ social media. For example, future research can include different professional sports leagues, such as the NFL, MLB, NHL, and MLS, to explore if different CSR-related discourses are created between the organization and fans compared to the NBA. In addition, as this study focused on CSR activities that occurred after the global pandemic, future research should also consider if there is a difference in discourses from both professional teams and publics from CSR activities held after the pandemic.

Conclusion

Professional sports teams’ CSR activities are regarded as a prominent issue as the public feels strong bonding with professional sports teams and expects them to give back to the community (Babiak & Wolfe, 2009; Stoldt et al., 2012). In response to the public’s expectations, the NBA has organized CSR activities with the NBA Together program and initiated the #NBATogether campaign after the COVID19 global pandemic. However, while many studies have analyzed how social media platforms are utilized during risk and crisis, there lacked studies in utilizing the public’s voice in social media platforms. Therefore, this study utilized Fairclough’s CDA process to analyze the voices of professional sports teams and the public by comparing discourses reflected in Twitter posts and comments.

Findings revealed that while most of the public supported professional sports teams’ CSR activities by creating complying discourse in comments, some challenging discourses could be found constantly in comments. Our study suggested that as users following professional sports teams in social media are passionate fans, both social media and traditional media should also be considered when delivering CSR discourses. Therefore, this research provided a foundational step in analyzing the voice of the public’s in social media and how other forms of media should also be considered when analyzing the public’s voices regarding CSR activities.