Team Branding Enhancement: The Role of Player-Team Brand Personality Alignment in Team Evaluation and Brand Equity

Article information

Abstract

Although the primary purpose of signing players is to provide fans with the best on-field performance, players’ role in team branding is another important factor that needs to be considered. Furthermore, as teams are dedicating tremendous time and effort into scouting and with large talent pools available worldwide, teams can easily find players with similar on-field qualities but possess dissimilar brand personalities. Thus, the purpose of the current study is to investigate the role of player signing in team branding. Particularly, this study examined the effect of player-team brand personality alignment on team-related fan responses. The empirical evaluation was undertaken with data collected from an experimental study. The authors empirically demonstrated that player-team brand personality alignment positively affected overall team evaluation and customer-based team brand equity, with more pronounced result for unfamiliar teams. Our findings not only establish the vital role of players in teams’ branding strategies but also uncover when aligned brand personality is more influential in reinforcing brand meaning and shaping affective brand evaluations and customer-based brand equity. The results of the current study fill gaps in the literature and extend the body of knowledge in branding studies in general and sports team branding studies in particular.

Introduction

In today’s competitive marketplace, professional sports teams can no longer gain competitive edge over other entertainment options purely on the basis of what products or services they offer (Buhler & Nufer, 2009; Keller & Richey, 2006; Ross et al., 2008). In other words, the success of a professional sport team now equally relies on ‘who’ the team is as to ‘what’ the team does (Keller & Aaker, 1998) and the former (i.e., how a team displays itself to current and potential fans) can be defined through brand personality (Keller & Richey, 2006).

Defined by Aaker (1997) as “the set of human characteristics associated with a brand” (p. 347), brand personality provides a tangible reference point which is more vivid than the sense conveyed by a generic offering (Upshaw, 1995). In the similar vein, a well-established and managed team brand personality can help generate a set of favorable associations in consumer memory (Johnson et al., 2000; Keller, 1993), which influences fans’ attraction to the team (Carlson et al., 2009), and ultimately builds and enhances team brand equity. Due to these benefits, more professional sports teams are starting to invest significant time and effort in developing, managing, and strengthening team-selected brand personality (Keller & Lehmann, 2006).

Although team brand personality can manifest along several determinants such as team logo, owner(s), head coaches, and stadium/arena, players are one of the most influential mediums as they produce the core product (i.e., the game) and are the most visible team personnel (Mullin et al., 2007; Opie & Smith, 1991). Furthermore, as professional sports have developed into a highly commercialized industry segment, players nowadays achieve individual celebrity status among fans (Carlson & Donavan, 2013).

Due to their influential status in the realm of professional sports, players have been at the forefront of the team branding efforts. These trends are supported by extant studies which report the positive effect of star players on their respective team image (Carlson & Donavan, 2008; Foster et al., 2016) and team brand equity (Pifer et al., 2015). However, players can also cause damage in team image or brand with their misbehavior committed off of the court or field (Parlow, 2009) and this can be a huge liability for teams as they are very difficult to control. Furthermore, these so-called ‘star player branding’ needs to be considered with caution as player mobility at the professional team sport level is very high in today’s professional sport environment (i.e., only a few players stay with the same team for their entire career) (Mullin et al., 2007) and as these big-name players generally have high price tag and not many teams can afford these players. Therefore, the current study focuses on team driven branding rather than star player driven branding—i.e., team selected and controlled branding through non-star players.

Professional sports players are human brands which possess individual brand personality (Carlson & Donavan, 2013) and they are one of the key factors in the generation of brand equity of a team. Player brands are capable of effecting the identities of their teams by imputing value from their personal identities (Pifer et al., 2015). Therefore, in team branding perspectives, it is crucial for teams to identify and understand each player’s brand personality as they collectively depict and convey the team brand meaning (Pifer et al., 2015). Although there are different ways which the teams, either intentionally or unintentionally, convey branding messages through players, ‘a team signing a player’ context is one of the most frequent branding cues fans are exposed to in today’s professional sporting world (Pifer et al., 2015). Player signing and player transfers are frequently witnessed practice and the event garners substantial media coverage which leads to speedy dissemination of the signing.

Consequently, in order to maintain consistent team-selected brand personality appeal through players, teams need to consider, when signing, the player’s brand personality (ideally brand personality that aligns with that of the team). However, this is very rarely witnessed in practice as player signing decisions heavily depend on the team budget and player’s performance-based qualities rather than extrinsic aspects related to team branding.

Although the primary purpose of signing players is to provide fans with the best on-field performance, players’ role in team branding is another important factor that needs to be considered—especially in a cluttered marketplace where numerous entertainment options are available. Furthermore, as teams are dedicating tremendous time and effort into scouting players and with large talent pools available worldwide, teams can easily find players with similar on-field qualities but possess dissimilar brand personalities.

Furthermore, as extant studies (e.g., Aaker, 1991; Keller, 1993; Kent & Allen, 1994) report that consumers exhibit purchase behavior variations depending on brand familiarity, it is only logical to suspect that team familiarity may play a moderating role on the effects of player-team brand personality alignment. Brand familiarity, which is acquired through brand experience, affects consumers’ intake of brand’s marketing messages (Campbell & Keller, 2003; Keller, 1991; Stammerjohan et al., 2005). In other words, when exposed to brand’s marketing messages, consumers who are familiar with the brand already tend to undertake less extensive processing, while employing more extensive processing for unfamiliar brands (Hilton & Darley, 1991; Keller, 1991). In line with the former studies, the authors assume that when people are familiar with the team, as their level of information search is negatively moderated by their level of familiarity, the effect of athlete-team brand personality alignment message (i.e., an information cue) on overall team evaluation will be weaker. Therefore, the current study formulated team brand familiarity as a moderator in the research model.

Thus, the purpose of the current study is to investigate the role of player signing in team branding. Particularly, the authors investigated the effect of player-team brand personality alignment on team-related fan responses. Furthermore, the authors examined the conditions (i.e., team familiarity) under which this alignment has a stronger influence on team brand evaluations.

Conceptual development and hypotheses

The effect of player-team brand personality alignment

As previously mentioned, brand personality plays a pivotal role in team branding (Keller & Aaker, 1998) and players are one of the most powerful and influential mediums in team branding (Carlson & Donavan, 2008, 2013; Kapferer, 2008; Till & Busler, 2000). Several extant studies examined the role of star players on team image and team brand (Carlson & Donavan, 2008; Foster et al., 2016; Pifer et al., 2015). For instance, Carlson and Donavan (2008) investigated that fans’ level of identification with a player is positively transferred to their attitude toward the team, which in turn positively affected team-related outcomes.

Given this reality, it is fair to argue that implementing team branding communication by strategically aligning player brand personality with that of the team is an effective method as it offers marketing managers a cohesive approach to convey team brand as a unified whole (i.e., minimizing confusion). Hence, teams should consider player’s brand personality when considering to sign a player. The current study postulates that the alignment shall serve as a congruent and clear marketing message which will increase the brand-related congruity, thereby facilitating fans’ understanding of the conveyed team brand’s meaning. To conceptualize the positive effect of brand personality alignment, schema congruity theory and congruence theory are cited.

The former theory, which has been used to explain the effects of congruence (Cornwell & Maignan, 1998; McDaniel, 1999), provides explanation as to why people tend to respond more positively to congruent information (Meyers-Levy & Tybout, 1989). A schema is a cognitive structure that represents a type of stimulus that includes a person, event, or place (Taylor & Crocker, 1981). This organization of knowledge is developed through experiences over time and influences information processing such as encoding, comprehension, retention, and retrieval of information. Schema congruity theory posits that congruent information lessens the cognitive processing, which leads to less cognitive elaboration and frustration, and ultimately results in positive evaluation (Mandler, 1982).

In line with schema congruity theory, congruence theory also suggests that congruent information is more clearly remembered in the consumers’ mindset (Lee & Cho, 2009). That is, when a stimulus and its context are aligned, the conveyed information (i.e., brand meaning) is more easily grasped and, therefore, is more accessible in memory relative to misaligned stimulus and context (Sirianni et al., 2013).

Therefore, based on the aforementioned conceptualization of schema congruity theory and extending the concept of congruence theory, when player brand personality is aligned with the team brand personality, the congruent marketing communication will enable fans to experience the team brand as a more consistent, unified whole. This process shall have a significant influence on increased preference (Lee & Labroo, 2004; Reber et al., 2004) and, thus, more favorable overall brand evaluations and customer-based brand equity (Sirianni et al., 2013). H1 is formally stated as follows:

H1a: Overall team evaluation will be more favorable when the player brand personality is aligned with the team brand personality than when misaligned.

H1b: Customer-based team brand equity will be more favorable when the player brand personality is aligned with the team brand personality than when misaligned.

Overall team evaluation and customer-based team brand equity are the two dependent measures chosen for the current study. The former measures customers’ affective responses toward the team brand (such as liking, trust, and desirability), while the latter measures managerial implications of brand building (such as degree of brand equity benefits compared to competitors, perceived value for the cost, and brand uniqueness) (Netemeyer et al., 2004).

The moderating role of team familiarity

Brand familiarity is defined as knowledge acquired through direct or indirect experiences with a brand (Alba & Hutchinson, 1987; Kent & Allen, 1994). Due to its role in determining the degree of information processing motivation, brand familiarity affects customer’s degree of intake of new brand-related information (Campbell & Keller, 2003; Keller, 1991; Stammerjohan et al., 2005). Following this line of literature, customers undertake less extensive processing when exposed to brand information regarding familiar brands, while employing more extensive processing for unfamiliar brands (Hilton & Darley, 1991; Keller, 1991).

Building on the existing literature, the authors suggest that player-team brand personality alignment will have a stronger effect for unfamiliar teams than for familiar teams. This prediction can be explained through the different information processing methods undertaken by fans’ top-down and bottom-up information processing. Fans will likely employ top-down information processing (i.e., less extensive) when they encounter a new brand-related message conveyed by familiar teams (Schwarz, 2002). This type of information processing is characterized by less focused attention and relies on fans’ general knowledge. In other words, fans will judge a team brand based on information accumulated through past experiences with the team (i.e., prior knowledge) rather than the team branding cues conveyed through player-team brand personality alignment.

On the other hand, when fans are exposed to brand information cues of unfamiliar teams, they tend to engage in bottom-up processing (i.e., more extensive) (Schwarz, 2002). Contrary to the prior, this processing style is accompanied by focused attention to new brand information cues. In other words, fans will engage in more elaborate cognitive evaluation by in-taking the new brand cues. Based on the different information processing styles undertaken by fans, the current study posits that player-team brand personality alignment will have a stronger positive effect on fans’ team brand-related judgments of unfamiliar teams compared to familiar teams. From H1 and aforementioned line of reasoning, H2 is stated as follows:

H2a: Positive effect of player-team brand personality alignment on overall team evaluation will be stronger for unfamiliar teams than for familiar teams.

H2b: Positive effect of player-team brand personality alignment on customer-based team brand equity will be stronger for unfamiliar teams than for familiar teams.

Team and player brand personality measures

The framework for team and player brand personality proposed by Carlson et al. (2009) and Carlson and Donavan (2013) serve as the basis for this study. According to these studies, the brand personality scale (BPS) developed by Aaker (1997) was meant for traditional, tangible product brands. However, sport teams and players are intangible brands to which the BPS is not applicable. In other words, some of the attributes in the BPS may not directly apply to sport context. Therefore, aforementioned studies identified one attribute from each dimension to be highly relevant in describing team and player brand personality. Moreover, each of the brand personality attributes used in these studies demonstrated strong face validity and was representative of the original five dimensions of brand personality proposed by Aaker (1997). Consistent with former studies, the current study adopted the individual attributes identified by Carlson et al. (2009) and Carlson and Donavan (2013). Among the five attributes from the former studies (wholesome, imaginative, successful, charming, and tough), the authors purposefully chose two clearly distinguishable and easier to manipulate attributes as those two were relatively easier to manipulate in experiment setting Furthermore, these two brand personality attributes were successfully manipulated the misaligned situation in former studies (e.g., Carlson & Donavan, 2013; Carlson et al., 2009). Thus, the current study utilized two brand personality attributes for a team and players: imaginative (excitement dimension) and tough (ruggedness dimension).

Mathods

The current experiment empirically examined hypotheses with two different brand personality attributes (imaginative and tough). Some respondents were exposed to a player-team brand personality aligned scenario (imaginative team / imaginative player), whereas others were exposed to a player-team brand personality misaligned scenario (imaginative team / tough player). In a 2 × 2 between-subjects factorial design, the authors manipulated player and team brand personality (aligned vs. misaligned) and team familiarity (familiar vs. unfamiliar).

Respondents

A total of 121 undergraduate students at three national universities in Korea participated in the study. Undergraduate students were recruited via their enrollment in sport-related courses. The samples were purposefully selected because the stimuli provided in the study were likely to be relevant to the students as they have interest in sports. Respondents were randomly assigned to one of four conditions (i.e., randomly provided different stimulus materials). Among the total of 121 respondents, after data screening (i.e., data entry error or implausible values for each variables), 112 survey data were deemed usable for further data analysis. The final respondents consisted of 95 males (84.8%) and 17 females (15.2%) with an average age of 23.1 years (SD = 2.17).

Procedure

The experiment took place in a classroom setting, wherein the respondents were randomly assigned to one of four different treatment conditions. The material was in a fictitious newspaper article format which was made to appeal to the respondents in a more realistic manner. After reviewing the material, respondents completed the questionnaire which measured dependent variables of interest, covariates, and series of manipulation check questions. The number of samples (minimum of 20 samples per cell: a total of 80 samples) in each cell was determined using G*Power program (Faul et al., 2007).

Covariates

Involvement is one of the most frequently controlled variables as it affects people’s cognition, attitude, and behaviors. In the similar vein, sport involvement can influence the manner in which respondents process information conveyed through aligned brand personality. In other words, when people are exposed to the new information cue (i.e., player-team brand personality alignment), depending on their level of involvement toward soccer, it is fair to argue that their level of information intake will be different. This difference, in turn, will hinder the true effect of player-team brand personality alignment as a marketing communication message.

Another important covariate measured in the current study was respondents’ perceived likeability of the players and teams. Drawing from the psychology literature, likeability has been defined as a persuasion tactic and a scheme of self-presentation (Kenrick et al., 2002; Reysen, 2005). In the context of celebrity endorsements, a research suggests using celebrities is a way for firms to induce likeability, aiming to create positive associations with a firm’s services and that such a front figure would capture the customers’ attention and create brand loyalty (McCracken, 1989). In the similar vein, as familiar players and teams are generally likeable, effect of brand personality alignment (i.e., brand information cue) can be affected by the degree of people’s likeability of the players and teams used in the stimulus materials.

The last covariate controlled in the current study was respondents’ perceived quality of the players and teams. Perceived quality, consumer’s judgment of the degree of a product’s overall excellence or superiority (Tsiotsou, 2006), is a subjective decision made by an individual which leads to preference and consequently satisfaction, loyalty, sales, and profitability (Mitra & Golder, 2006). Therefore, the authors posit that perceived quality of the players and teams can affect the effect of player-team brand personality alignment on dependent variables.

Building on these extant studies and reasoning, it is fair to argue that respondents’ involvement in soccer, likeability and perceived quality of the players and teams may interfere with the effect of the new team branding information (i.e., aligned player-team brand personality). Therefore, in order to investigate the true effect of the brand personality alignment, aforementioned three variables were measured as covariates to control the potential effect of those variables.

Measurement

First, respondents’ overall team evaluation was measured by five scale items to capture perceptions of team liking, team trust, team quality, team desirability, and team related purchase likelihood (Aaker 1991; Dawar & Pillutla, 2000; Sirianni et al., 2013): (1) Overall, how do you feel about the team? (dislike - like/not at all trustworthy - very trustworthy / very low quality - very high quality / not at all desirable - very desirable); (2) If you have the chance, how likely are you to visit or watch the team’s match? (not at all likely-very likely). For hypotheses testing purposes, an overall team brand evaluation index was created by averaging the five measures (α = .91).

Another dependent measure of the current study, customer-based team brand equity was assessed by four scale items (very strongly disagree – very strongly agree) capturing perceptions of quality versus competitors, value for the cost, team brand uniqueness, and willingness to pay a premium for the team brand (Netemeyer et al., 2004; Sirianni et al., 2013): (1) The team brand is one of the best brands in professional soccer; (2) The team brand really ‘stands out’ from other professional soccer teams; (3) I am willing to pay more for the team’s match ticket than other professional soccer team matches; (4) Compared with other professional soccer teams, the team’s brand value is a good value for the money. For the same purpose, a customer-based team brand equity index was created by averaging these four measures (α = .90).

Next, the covariates were measured. Based on former studies (e.g., Bristow & Sebastian, 2001; Jones et al., 2004; Ross et al., 2006; Shank & Beasley, 1998; Zeithaml, 1998), soccer involvement, team/player likeability, and team/player perceived quality were deemed to interfere with the effect of the new team branding information. Soccer Involvement was measured using ‘Sport Involvement Scale’ developed by Shank and Beasley (1998) and the items in this scale were combined to form the involvement index (α = .75). Respondents’ likeability of the teams and players used in the stimulus materials were measured by three scale items from formers studies (Bristow & Sebastian, 2001; Jones et al., 2004) and these items were combined to form the likeability index (αteam = .83, αplayer = .88). Respondents’ perceived quality of the players and teams were measured by two items each, selected (and modified) from Zeithaml’s (1998) perceived quality scales and Ross et al.’s (2006) ‘Team Brand Association Scale’. The items were combined to form the perceived quality index (αteam = .89, αplayer = .81).

After completing the dependent and covariate measures, respondents answered manipulation check questions, which included their perceived degree of player-team brand personality alignment and player and team familiarity. Respondents’ perceived player-team brand personality alignment was assessed by three scale items (very strongly disagree – very strongly agree) and the three measures were: (1) The team and the player have a similar brand personality; (2) the personality I associate with the team is related to the personality of the player; (3) my personality of the team is very different from the personality I have of the player (the third item was reverse coded). These items were modified from a previous study on matching the effect of brand and sporting event personality (Lee & Cho, 2009) and were combined to form the alignment index (α = .97).

Respondents’ perceived team and player familiarity included three items each and items were adopted from Simonin and Ruth (1998): Please tell us how familiar you are with the team/player: (1) not familiar – very familiar, (2) do not recognize – do recognize, (3) have not heard of before – have heard of before. For hypotheses testing purposes, familiarity index for both team and player was created by averaging the three measures (αteam = .98, αteam = .85).

Data analysis

Several stages of pretesting were conducted to develop stimulus materials manipulating player-team brand personality alignment (aligned vs. misaligned) and team familiarity (familiar vs. unfamiliar). The stimulus materials contained general information of the team’s imaginative and player’s imaginative or tough brand personality positioning. The words used to offer a signal of the team’s and player’s brand personality were carefully selected from an ‘imaginative’ measurement tool developed by Cho, Lee, and Kim (2015) and from a thesaurus dictionary. For example, words used to depict ‘imaginative’ and ‘tough’ attributes were creative and innovative for the former and rugged and strong. The main aim of the pretest was (1) to identify teams with imaginative brand personality and players with either imaginative or tough brand personality, and (2) to verify familiar and unfamiliar teams.

In the pretest (N = 60), respondents were asked to evaluate, using a five-point scale (anchored by 1 = not at all agree, 5 = extremely agree), the degree of brand personality alignment (team and player brand personality) and the degree of their familiarity with the teams and players. A series of one-way analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were performed to test manipulated brand personality alignment and familiarity. First, respondents rated aligned scenarios as more aligned than misaligned scenarios (Maligned = 3.82 vs. Mmisaligned = 2.24; F(1, 58) = 91.373, p < .001). Second, the familiarity of the familiar team was significantly different from that of unfamiliar team (Mfamiliar team = 4.13 vs. Munfamiliar team = 1.83; F(1, 58) = 176.484, p < .001), whereas player familiarity did not differ among the four groups (F(3, 56) = .921, p > .05). Taken together, the results of these pretests provided evidence that selected teams and players convey intended information. Therefore, two teams (familiar and unfamiliar teams with imaginative brand personality) and two players (unfamiliar players with imaginative and tough brand personality) were used in the manipulation scenarios for further analysis. Unfamiliar players were purposefully used in all four categories to minimize any potential confounding effect of player familiarity.

A statistical package (SPSS 20.0) was used to analyze the validation of measurement items and to test hypotheses. Reliability test was undertaken to test the consistency of the measures, while a 2×2 multivariate analysis of covariance (MANCOVA) with the overall brand evaluation index and the customer-based brand equity index as dependent variables was conducted to test research hypotheses. All statistical significance was assumed at a .05 level.

Results

Internal consistency and manipulation check

Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were all above the recommended .70 threshold (Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994), ranging from .75 to .98, indicating that the constructs were internally consistent. A series of one-way ANOVAs were conducted to demonstrate whether the manipulated player-team brand personality alignment levels differed significantly from one another; and whether the two operationalized conditions of team familiarity differed significantly from each other. First, ANOVA with alignment as the dependent variable revealed statistically significant difference between aligned groups and misaligned groups (Maligned = 5.84 vs. Mmisaligned = 1.86 [out of 7]; F(1, 110) = 1151.194, p < .001). Second, ANOVA with team familiarity as the dependent variable also revealed statistically significant difference (Mfamiliar team= 6.31 vs. Munfamiliar team = 1.55 [out of 7]; F(1, 110) = 1797.674, p < .001). Taken together, the results provided evidence that intended alignment and familiarity were successfully manipulated.

Preliminary analysis

Data for the four experimentally manipulated groups are displayed in Table 1 below. A 2×2 MANCOVA with the overall team brand evaluation index and the customer-based team brand equity index as dependent variables, soccer involvement, team/player likeability and team/player perceived quality as covariates, and alignment and team familiarity as independent categorical variables was conducted. Levene’s tests for each dependent variable were statistically insignificant (all values p > .05), indicating equality of error variances across the treatment groups on each dependent variable. In addition, Box’s M test was statistically insignificant (all values p > .001), indicating equality of variance-covariance matrices of the multiple dependent variables across the treatment groups. These results illustrated that the current study satisfied the assumptions for MANCOVA test.

Distribution, means, and standard deviation for four experimental conditions: Overall team evaluation and customer-based team brand equity

The two-way MANCOVA interaction between alignment and team familiarity was statistically significant [Wilks’ λ (Lambda) = .896, F(2, 102) = 5.948, p = .004; for full results, see Table 2], allowing separate use of ANOVAs for the two dependent variables with the protection of the Type 1 error rate. In support of H1a and H1b, there was a significant main effect of alignment on overall team brand evaluation [F(1, 103) = 15.917, p < .001] and customer-based team brand equity [F(1, 103) = 15.510, p < .001]. Meanwhile, player perceived quality was the only covariate variable which yielded significant main effect on team brand equity.

Effect of player-team brand personality alignment on overall team evaluation and customer-based team brand equity

Respondents gave higher overall team brand evaluations when player-team brand personality was aligned (M = 4.63) than when misaligned (M = 4.10; F(1, 103) = 15.917, p < .001), in support of H1a. Furthermore, in support of H1b, respondents also gave higher customer-based team brand equity ratings to aligned groups (M = 4.61) than to misaligned groups (M = 4.10; F(1, 103) = 15.510, p < .001). Moreover, team familiarity did not exert a significant main effect on overall team brand evaluation [F(1, 103) = 3.511, p > .05] nor on customer-based team brand equity [F(1, 103) = 1.785, p > .05]. These results are notable because they indicate that the team familiarity did not significantly influence respondents’ responses to team brands independent of player-team brand personality alignment manipulation.

Player-team brand personality alignment x team familiarity interaction

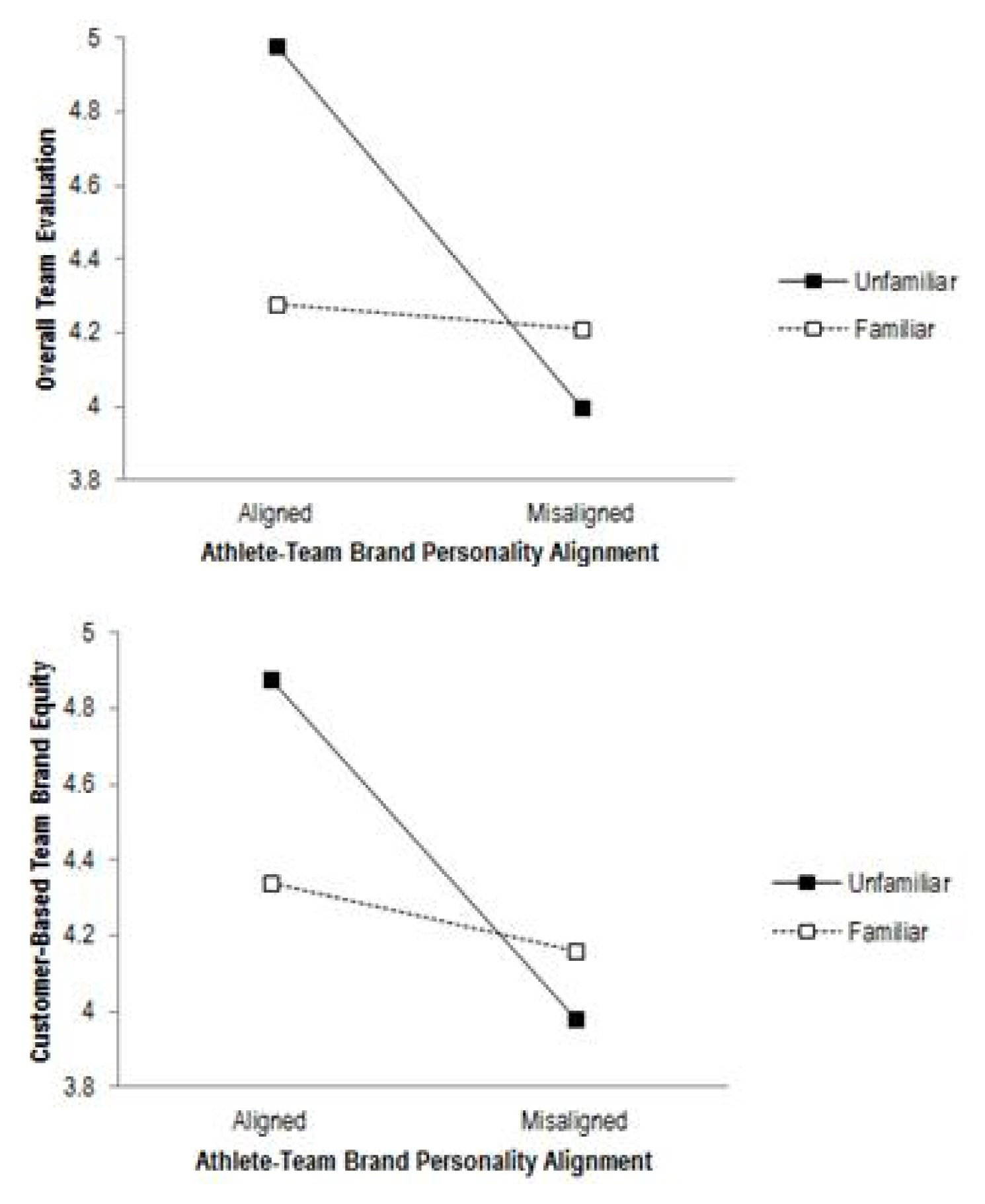

As mentioned above, a two-way MANCOVA using the overall team brand evaluation [F(1, 103) = 11.409, p < .01; see Figure 1] and customer-based team brand equity [F(1, 103) = 6.661, p < .05; see Figure 1] as the dependent variables and player-team brand personality alignment and team familiarity as independent variables revealed a significant two-way interaction. This statistically significant interaction effect was examined further by performing simple effect test. In support of H2a, respondents in the aligned group rated .702 points higher for unfamiliar team than for familiar team (p < .001, 95% CI of the difference = .334 to 1.071). In contrast, overall team evaluation did not differ across familiar and unfamiliar teams for respondents in the misaligned conditions (p = .281).

Similarly, consistent with H2b, for aligned conditions, customer-based team brand equity was significantly higher when the team was unfamiliar than familiar (p < .01, 95% CI of the difference = .160 to .918). Meanwhile, for misaligned conditions, there was no significant difference in customer-based team brand equity due to team familiarity (p = .373).

Discussion and conclusion

Theoretical implications

Using sports players is a common, frequently noticed practice in advertising campaigns. Despite the large cost required to secure player endorsers, this promotional strategy is still very popular as players are influential human brands—players are the most frequently selected endorsers compared to any other celebrities (i.e., musicians, actors, comedians, etc.) (Carlson & Donavan, 2008; Lake et al., 2010). However, team branding using star players is not team controlled nor team driven and it is almost impossible to witness star players spending their entire career with a single team. In other words, despite the positive effect of star players on team branding (Carlson & Donavan, 2008; Foster et al., 2016; Pifer et al., 2015), it can also be a risk for teams if they rely their team branding on a single star player. Furthermore, not many teams possess enough budgets to meet the high price tag on those star players. Therefore, the authors focused on team driven branding particularly with non-star players rather than star players. Hence, the purpose of the current research was to empirically examine the direct link between player-team brand personality alignment to team evaluation and customer-based team brand equity, as well as moderating role of team familiarity in relation to strategic alignment. The current study measured two distinct scales as dependent variables in order to provide more detailed and profound implications for team marketing managers. The result of the current research fills the gap in the literature and extends the body of knowledge in branding studies in general and sports team branding studies in particular.

Hypothesis 1 was fully supported, meaning that player-team brand personality alignment has a positive effect on overall team evaluation and team brand equity evaluation. In other words, fans tend to evaluate teams more positively as their perception of the degree of brand personality alignment increases. This is consistent with existing studies as aligned and unified information is easier to process and understand which, in turn, leads to conceptual fluency and increased preference (Lee & Labroo, 2004; Reber et al., 2004). These results are also partially supported by the extant studies in the field of sport sponsorship and player endorsement (e.g., Gwinner, 1997; Gwinner & Eaton, 1999; Kamins & Gupta, 1994; McDaniel, 1999; Till & Busler, 2000), which report that congruence between sponsor and sponsored entity or endorser and endorsed entity has positive influence on desired outcomes.

The current study is one of the first studies to empirically examine the role of player-team brand personality alignment in reinforcing team brand personality communication—i.e., team branding. This is a notable contribution because, despite the increasing importance of players and their power of appeal, extant studies have not examined the role of players in building favorable fan outcomes such as overall team evaluation and team brand equity.

Furthermore, hypothesis 2 was also supported. This means that the effect of alignment on team evaluation is milder when fans are more familiar with the team. This is an important finding because the results demonstrated how unfamiliar teams (or newly inaugurated teams) can leverage brand personality alignment when they build their positioning in both current and potential fans’ minds. This negative interaction effect of team familiarity is supported by bottom-up information processing as people tend to undertake more extensive information processing for unfamiliar brands (Hilton & Darley, 1991; Schwarz, 2002). This also is an important contribution to the existing literature because the result uncovered when the player-team brand personality alignment is most influential in reinforcing brand meaning and shaping affective brand evaluations and brand equity. Furthermore, based on the findings of the study, the authors provided guidance for successful adoption of brand personality alignment in sports, which should prove insightful for marketing managers and academics.

Many extant studies (e.g., Gwinner, 1997; Gwinner & Eaton, 1999; Kamins & Gupta, 1994; McDaniel, 1999; Till & Busler, 2000) in the field of marketing and sport management have already provided empirical support for the effects of sponsor-sponsored entity or endorser-product congruence, fit, or alignment on consumer responses. However, these extant studies have primarily deemed players as a marketing medium for outside firms. Therefore, the current study is distinguishable as strategic alignment of player-team brand personality is concerned with an internal source (i.e. players of a team), whereas extant studies are concerned with an external source (i.e. players as an endorser). This difference entails marketing effectiveness as the process of developing, managing, and maintaining a brand through an internal source can be less troublesome compared to outside sources.

Practical implications

Based on the findings, the authors suggest that teams should consider player’s brand personality prior to making the final decision. It is important because players are the ‘human brands’ and represent a powerful brand-building asset for teams. Although the primary purpose of signing players is to uplift team’s on-field performance, team branding is also becoming more important in today’s crowded service/entertainment marketplace. Therefore, as player-team brand personality alignment has a positive effect on overall brand evaluations and customer-based brand equity, player brand personality should be an aspect taken into consideration when considering to sign a player.

In addition, as the effect of brand personality alignment is more robust for relatively unknown teams, marketing managers of newly inaugurating teams or relatively unfamiliar teams should consider undertaking this branding method. Based on the findings of the current study, unfamiliar teams, through player-team brand personality alignment appeal, can match—or even surpass—more familiar teams in terms of overall team brand evaluations. This finding can also be of interest to more familiar teams as signing brand personality aligned players may not offer brand enhancing advantage to the same degree. However, as there are more teams without a clear brand image (Bauer et al., 2008), player signing can be an effective team branding too for many existing teams.

Based on the findings, the authors suggest that teams should train and motivate players to perform their service roles in a manner that represents the team’s selected brand personality. It is important for the players to truly realize their responsibilities as the ‘human brand’ and represent a powerful brand-building asset for teams. In addition, in order to maximize the effect of unified team branding message, marketing managers should deliberately design and direct their team brand positioning efforts. Furthermore, as the effect of strategic alignment is more robust for relatively unknown teams, marketing managers of newly inaugurating teams or relatively unfamiliar teams should consider undertaking this branding method.

Moreover, to implement strategic alignment successfully, the authors suggest that marketing managers or decision making team officials work closely with their coaching staffs or scouting team to nurture or sign players who naturally possess team aligned brand personality. The authors understand that signing players who has corresponding brand personality is difficult for teams. Especially for professional sports where winning is a goal of the utmost importance and, therefore, either nurturing or signing players based on their brand personality cannot be on the top of the checklist. However, as F.C. Barcelona stands as a successful example, it is not impossible to pursue a certain brand positioning and be competitive simultaneously. F.C. Barcelona has implemented the team color, which is known as “Tiki-Taka”, and maintained that color for over several decades and still stands as a giant in international football. It is a style of play characterised by short passing and movement, working the ball through various channels, and maintaining possession (Chopra, 2013). It is implemented by Barcelona in 2009 and the color is now deep rooted into the club and is one of a few professional sport teams with distinct and pronounced brand image (Hamil et al., 2010).

Limitations and future research

Although the results of the current study are consistent and robust, the authors recognize several limitations that must be taken into account when generalizing the results of the current research. The first limitation is the specific sport being used in the experiment (i.e., soccer). Thus, the findings may have been influenced by the characteristics of soccer and may be difficult to generalize the results to professional sports in general. Therefore, additional samples from different types of sports should be collected in future researches to further clarify the effect of player signing in team branding efforts.

Furthermore, the samples were limited to students taking sport-related courses. Although the samples were purposefully selected due to their interest and familiarity in sports, the results may have been influenced by the specific characteristics of the specific sample and lack generalizability to sports team branding setting in general. Additional samples such other groups of fan bases and fans in other countries should be collected in future research to further clarify our understanding of the role of alignment in team branding. Moreover, although an experimental setting provides several advantages, future researches should be undertaken in a real-life setting where teams are undertaking branding efforts with their players. This would deepen our understanding of utilizing players in team branding.

We also call for additional research that investigates the effect of different types of alignment. The current study manipulated brand personality alignment by purposely matching players’ style of play with that of the team brand personality. However, it remains unclear whether findings would be similar if a different alignment manipulation was used. Therefore, future researches may manipulate player’s physical appearance, outwear, or other branded tangibles to align (misalign) with the team brand personality to further investigate the effects of alignment on team evaluation. Lastly, future studies might uncover player-team brand personality alignment’s relationship to actual fan spending to fully understand the financial benefit accrued through this integrated branding strategy.