The Relationship among Authentic Leadership, Trust in Coach, and Group Cohesion of College Soccer Players

Article information

Abstract

The purpose of this study was to analyze the relationship among players’ perceptions of authentic leadership, trust in coach, and group cohesion. Male college soccer players responded to questionnaire items about these three factors. A total of 249 survey data were analyzed by structural equation modeling. Authentic leadership had a significant positive relationship with trust in coach and group cohesion; trust in coach had a significant positive relationship with group cohesion; and trust in coach was a mediator in the relationship between authentic leadership and group cohesion. These findings suggest when coaches are authentic leaders, athlete and team outcomes may benefit.

Introduction

In June 2020, a Korean female triathlon athlete took her own life after sending her mother a text message asking her to punish her abusers through social media. In a journal she left behind, the team’s coach, doctor, and captain were all revealed to have abused her physically and psychologically over a period of years. Other coaches have been accused of sexual assault and embezzlement of team funds, revealing a widespread pattern of corruption and abuse in the country’s sports community. Such instances of abuse are increasingly being brought to light by athletes internationally. In the United States, a former USA Gymnastics national team doctor is serving 40 to 175 years in prison for using physical examinations as an opportunity to molest scores of female gymnasts (Choe, 2020). Such cases and many others suggest that urgent action is required to improve the system to protect the human rights of athletes, and that ethical and authentic leadership is critically important in sports.

Leadership in a sports context is defined as a behavioral process that influences players and teams to achieve the team's goals (Chelladurai, 1978). The ultimate goals can be understood as the victory of the team, the achievement of the aspirations of the players, and the realization of successful career paths of the leader and athletes. This study of psychological variables (trust and cohesion) related to authentic leadership has the potential to improve the performance of coaches, athletes, and teams (Gervis, Rhind, &Luzar, 2016; Kavanagh, Brown, & Jones, 2017; McMahon, Zehntner, McGannon, & Lang, 2020).

Therefore, the purpose of the current study is to understand the impact of authentic leadership on college soccer players by analyzing the relationship among authentic leadership, trust in coach, and team cohesion.

Literature Review

Authentic Leadership

The scholarship of leadership has evolved in recent years. Contextual fit theory, developed in the early 1990s, focuses on leadership appropriate to the characteristics of the management environment within a given organization. In particular, transformational and charismatic leadership have been found effective in situations where the external environment is unstable (Hur, Van den Berg, & Wilderom, 2011; Yukl, 2014). Even though these theories pay attention to actions that effectively respond to the changing external circumstances of the organization, they pay limited attention to the characteristics of the leader (Kim, 2018).

Starting in the early 2000s, “authentic leadership” began to emerge in business environments (Luthans & Avolio, 2003; Walumbwa et al., 2008). The concept of authenticity originated in Greek philosophy, as reflected by the aphorism “know thyself”, and the Greek origins of the word authentic, authenteo, meaning “to have full power” (Gardner et al., 2011). The two meanings (self-knowledge and power) were integrated by Kernis and Goldman (2006), who defined authenticity as having complete control over oneself. Kernis and Goldman identified four behavioral aspects of authenticity: awareness (of oneself), unbiased processing (of self-evaluative information), behavior (consistent with one’s own values), and relational orientation (openness, truthfulness, and genuineness in interpersonal relations). Authentic leaders seek to promote positive self-development, relational transparency, balanced information processing, internalized moral perspective, and a friendly ethical atmosphere (Walumbwa et al., 2008). Authentic leadership has a positive effect on organizational performance (Clapp-Smith, Vogelgesang, & Avey, 2009; Dirks & Ferrin, 2002; Lee & Hwang, 2016; Walumbwa et al., 2008; Wong & Cummings, 2009): when authentic leaders act in line with their purpose and members trust the leader's leadership, job satisfaction, organizational commitment, organizational citizenship behavior, and job performance of members increase. Authentic leadership also improves members’ level of trust in the leader, psychological well-being (Kwon & Jung, 2016), and organizational communication, and reduces turnover and counterproductive task behavior (Kwon, 2017).

Authentic leadership emphasizes a leader's personal characteristics such as self-awareness and self-regulation, rather than the leader's behaviors or skills in achieving profits or performance (Walumbwa et al., 2008; Clapp-Smith et al., 2009). The manifestation of leadership with sincerity increases the trust of members and induces members to think with the leader in specific situations (Yang, 2015). Kim & Lee (2019a) pointed out that authentic leadership could advance the process and results of sports organizations.

Authentic Leadership and Trust in Coach

Trust is a key concept indispensable for achieving job satisfaction, organizational goals and productivity, and self-realization of members (Cook & Wall, 1980). Based on the concept of trust, Johnson and Swap (1982) developed the concept of supervisory trust, a psychological state characterized by followers trusting and relying on the leader, a favorable attitude between members and leaders, and a positive emotional state that is felt in mutual relations. Dayan et al. (2009) found that the higher the level of trust within the organization, the more active the innovation and the higher the psychological stability among employees or group members. Trust has been shown to play a major role in bringing about organizational commitment and job satisfaction (Yang & Mossholder, 2010).

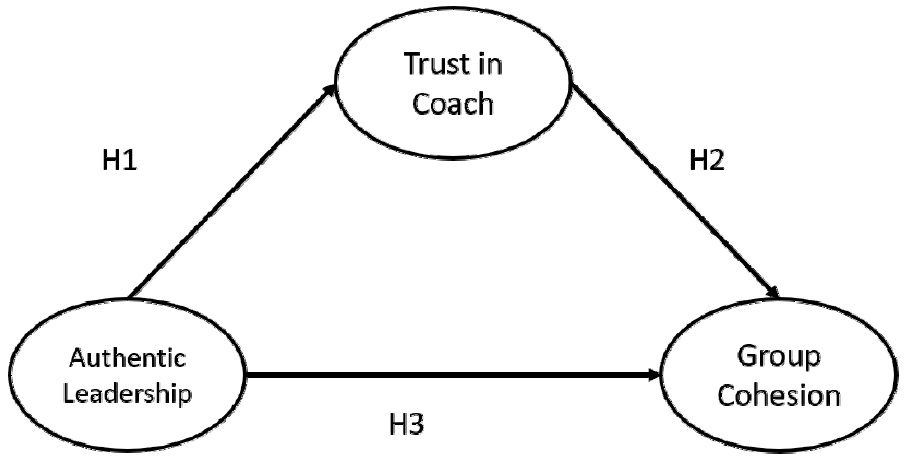

In sports situations, “trust in coach” positively affects the growth, individual performance, and team performance of players regardless of sport. Trust in coach develops through continuous interaction between players and leaders, and depends also on environmental factors. That is, it could be the case that even though players are guided through effective leadership, if the players do not accept the content of the instruction or do not trust the leader for some external reason, effectiveness of the coaching may be lost and performance goals may be difficult to achieve (Park, 2007). Therefore, in order to improve the growth and performance of players, it is necessary to understand the influence of authentic leadership on trust in coach. Building on the findings above, the following hypothesis is proposed: H1: Authentic leadership will have a significant influence on team members’ trust in their leaders.

Authentic Leadership and Group Cohesion

“Group cohesion” is the dynamic process of remaining united to achieve organizational goals (Carron, 1998). Group cohesion is reflected in the degree of friendship and trust among team members, the sense that they are led by a good leader, commitment to team performance, and the desire of members to stay on the team (Loughead & Carron, 2004; Philippe & Seiler, 2006). In the case of team sports such as soccer, where the ultimate goal is the team’s victory, it is necessary to pay attention to group cohesion through mutual effort and trust building in order to improve team performance.

Sports cohesion has dimensions of social cohesion and task cohesion. Carron, Hausenblas, and Eys (2005) proposed a conceptual system of sports group cohesion that includes environmental, individual, leadership, and team factors. With respect to leadership factors, the decision-making tendencies of the leader affect team cohesion and are reflected in the harmony and consistency of relationship among the leader and players.

Dienesch and Liden (1986) determined that based on the theory of social exchange, the more the members interact with the competent leader, the closer the relationship between the leader and members. Coaches who embodied authentic leadership while coaching a high school soccer team had a positive effect on team efficacy (Jeong & Hong, 2018), group cohesion (Kim & Youn, 2015), and team energy. They also enhanced the team's performance (Jeong & Kim, 2013). Correspondingly, the following hypothesis was formulated: H2: Authentic leadership will have a significant influence on group cohesion.

Trust in Coach and Group Cohesion

In an early study, Deutsch (1958) stated that in situations where uncertainty exists, trust is manifested when a person expects a certain thing to happen, and actions are triggered by that expectation. Since then, trust has been defined as the expectation that an individual or group could believe the oral or written words or promises of another individual or group (Rottter, 1967); the belief that the intentions of others are true and confidence in the competence of others (Cook & Wall, 1980); and the willingness to increase vulnerability to the behavior of an object beyond their control (Zand, 1972). That is, trust is generally understood as a social and psychological state (Rousseau et al., 1998).

In a sports situation, trust is a belief created through communication and harmony between a coach and a player. Previous studies have found a relationship between trust in the leader and group cohesion (Kang & Oh, 2015; Park, 2007). In a study of leaders of college team sports, Han (2017) found that trust in coach had a positive effect on team cohesion and played a major role in achieving the team’s goals. Based on the above studies, the following hypothesis 3 was proposed: H3: Trust in coach will have a significant effect on group cohesion. The first three hypotheses are schematically depicted in Figure 1.

Effect of Trust in Coach on Authentic Leadership and Group Cohesion

Previous studies have found (Clapp-smith et al., 2009; Giallonardo, et al., 2010) that trust in coach plays an important mediating role between authentic leadership and group cohesion. It is understood that authentic leadership increases the level of trust between coaches and players, and finally improves team cohesion. According to Dirks (2000), trust is a major variable influencing the effective operation and positive performance of an organization. Kim et al. (2020) found that trust in the leader had a mediating effect on the perceptions of authentic leadership and the innovative behavior of the organizational members. Yang (2015) found that trust partially mediated the relationship between authentic leadership and organizational commitment. Kim & Lee (2019) confirmed that the level of respect held for the leader was a major variable that mediated the relationship between authentic leadership and sports team effectiveness. Correspondingly, the following hypothesis was formulated: H4: Trust in coach will significantly mediate the relationship between authentic leadership and group cohesion.

Methodology

Participants and Data Collection

Data for this study were collected from male college soccer players who were registered in the Korea University Football Confederation (KUFC). with random sampling method. Soccer players were focused on this study because the performance of team sports like soccer could be improved based on the interdependent efforts and formation of trust between coaches and players. In December of 2019, after season, each team’s coaches were contacted randomly by researcher via phone call and email. Then, researcher visited each university in person to conduct paper and pencil-based survey. A total of 249 eligible participants completed the survey. The demographic variables for the respondents are shown in Table 1.

Measures

The survey consisted of 48 items (Table 2), which were compiled from several published survey instruments as detailed below. The reliability of the original instruments were verified in the cited studies. An expert panel consisting of a professor of sports psychology, a professor of measurement and evaluation, and a doctor of sports psychology reviewed and verified the compiled survey. All items were scored on a 5-position Likert scale.

Authentic Leadership

To measure authentic leadership, the current study employed seven items developed by Jeong and Hong (2018). Amomg Jeong and Hong’s original nine items, two were deleted due to their low squared multiple correlations (SMC) in the current study (Song, 2011). The Cronbach’s α of the seven remaining items was .883.

Trust in Coach

Trust in coach items were taken from the instrument developed by Jeon (2016). A total of 17 items (five relating to ability, five to benevolence, four to integrity, and three to diligence) were employed after deleting four items due to low SMC of the current study (Song, 2011). The Cronbach’s α of the 17 items ranged from .77 to .89.

Group Cohesion

Group cohesion was measured by items developed by Moon and Chun (2019) based on the Group Environment Questionnaire of Carron, Widmeyer, and Brawley (1985). After deleting seven items due to low SMC, 22 items (four relating to individual social cohesion, six to group social cohesion, five to individual task cohesion, and seven to group task cohesion) were employed (Song, 2011). The Cronbach’s α of the 22 items are ranged from .89 to 92.

Data Analysis

Data screening was conducted to find missing values using the Expectation-Maximization (EM) algorithm and to delete extreme outliers based on Mahalanobis distance values. Mardia’s (1975) multivariate kurtosis coefficient was 75.90, indicating non-normal distribution of data. Thus, Satorra-Bentler scaled chi-square (S-B χ2) and robust standard errors were employed (Satorra & Bentler, 1994). Next, a two-step approach suggested by Anderson and Gerbing (1988) was used. Specifically, the results of confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) were assessed to verify model fit indices, reliability, and validity of the measurement model. Next, to test the first three hypotheses, structural equation modeling (SEM) analysis was conducted. To assess model fit indices, this study used comparative fit index (CFI > .9), non-normed fit index (NNFI > .9), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA < .06), and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR < .08) (Hu & Bentler, 1999). Also, mediation effect of Trust in Coach between Authentic Leadership and Group Cohesion was measured based on Bootstrapping method of Preacher and Hayes (2008). The number of repetition estimation was set to 10,000 and tested by 95% confidence interval based on Cheung & Lau (2008).

Results

Measurement Model

The results showed that the CFA was acceptable (S-B χ2(df) = 1812.007(947), CFI = .912, NNFI = .923, RMSEA = .056, and SRMR = .057).

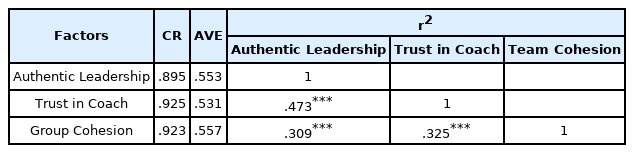

The present study assessed the reliability of the measures. The results showed that construct reliability (CR) coefficients ranged from .895 for authentic leadership to .925 for trust in coach, indicating good internal consistency for all scales (α > .70). Also, the convergent validity of each scale was assessed using the average variance extracted (AVE) values. The AVE values ranged from .531 for trust in coach to .557 for group cohesion, indicating acceptable convergent validity (AVE > .50) (Table 2). The discriminant validity was tested by comparing correlations between constructs and AVEs. The result revealed that the correlations were less than AVEs, indicating acceptable discriminant validity (Table 3).

Structural Model

This study measured the relationship among authentic leadership, trust in coach and group cohesion. The results showed acceptable model fit: S-B χ2(df) = 253.624(87), CFI = .945, NNFI = .930, RMSEA = .069, and SRMR = .061.

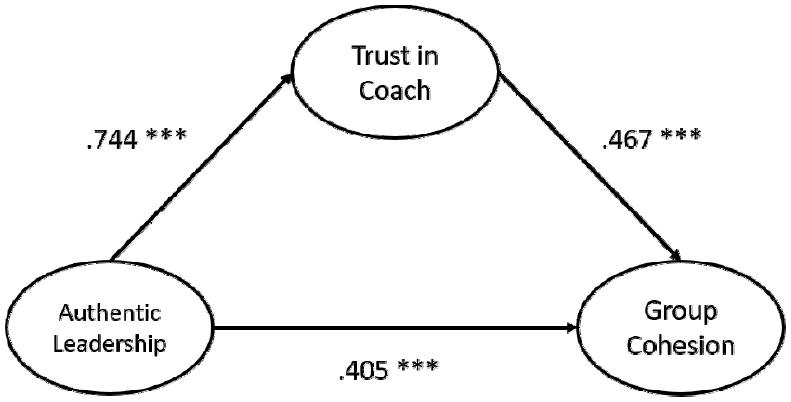

Using the t statistic, the four hypotheses were tested. For H1, H2, and H3, the results showed that authentic leadership positively affected trust in coach (β = 0.744, SE = 0.110, t = 6.763, p < 0.001) and group cohesion (β = 0.405, SE = 0.091, t = 5.139, p < 0.001). Trust in coach also positively predicted group cohesion (β = 0.467, SE = 0.099, t = 4.099, p < 0.001) (Table 4, Figure 2). For H4, mediation analysis showed that trust in coach had a mediation effect on the relationship between authentic leadership and group cohesion (β = 0.293, p < 0.001). In addition, the result indicated that there was a mediating effect because 0 (Zero) value was not included between the lowest interval (.220) and the highest interval (.536), (p<.001 (α=.000)).

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to understand how authentic leadership influences college soccer players by analyzing the relationship among authentic leadership, trust in coach, and team cohesion. First, these findings showed that authentic leadership had a positive impact on trust in coach. That is, if college soccer coaches demonstrate authentic leadership, trust that players invest in their coaches could be enhanced. This result is supported by previous studies that determined authentic leadership was closely related to the level of trust in a coach (Clapp-Smith et al., 2009; Giallonardo et al., 2010; Kim et al., 2018). The findings in the current study are also supported by Walumbwa et al. (2011), who found that when the coaches had a clear standard of integrity and made decisions in consultation with the members, the members had deep faith in their leaders. Additionally, previous studies (Bandura & Kavussanu, 2018; Bandura et al., 2016) confirmed that authentic leadership had a positive effect on player satisfaction, immersion, and enjoyment, which is consistent with this study. Furthermore, Kim & Lee (2019b) found that authentic leadership in a sports team situation had a positive influence with respect to the leader. Thus, the manifestation of such authentic leadership is believed to underpin the interactions between the coach and the players, resulting in trust that appears as voluntary, active, and complementary behavior of the players.

Second, these findings showed that authentic leadership had a positive effect on group cohesion. That is, the expression of authentic leadership of college soccer team coaches could increase the cohesion of the team. This result is supported by previous studies (Jensen & Luthans, 2006; Wong & Cummings, 2009) that showed that authentic leadership directly or indirectly affected the attitudes and behaviors of members of the organization. This manifestation of authentic leadership should be understood as a result of the coach knowing his or her own true beliefs, values and strengths, taking action that is consistent with those beliefs, and thus positively affecting the performance of members. In addition, this study confirmed that authentic leadership could improve the job satisfaction of members, their commitment to the organization, and cohesion their desire to stay in the organization by allowing them to consult with members and handle work in a balanced way when making important decisions.

Third, the current study found that trust in coach had a positive impact on group cohesion. This result is interpreted as meaning that the cohesion of the sports team can be enhanced by the interactions between the player and the coach. The importance of these interactions and the relationship between the coach and players should be considered paramount in importance, especially in the case of team sports such as soccer. This result is supported by the study by Dirks (2000), which found that among basketball players, trust in coaches led to positive effects on the players’ team and individual performances. In the case of team sports, positive interactions between the coach and players result in increased attachment to the team, which positively affects the group's performance (Han, 2017). Nam (2016) confirmed that among the variables that must precede improvement of group cohesion, a positive relationship between the coach and athletes was considered the primary variable. In addition, Huh and Ma (2013) found that among professional baseball players, trust in coach affected group cohesion but team trust did not cohesion. Leaders must make an effort to be sincere in their leadership and have a mindset to approach actively first (to think to be kind and try to make a relationship better) so that they can maintain a trusting relationship with the players.

Finally, this study found that trust in coach played a mediating role in the relationship between authentic leadership and group cohesion. That is, authentic leadership enhances team cohesion by means of increased trust between the coach and the player. Previous studies (Clapp-Smith et al., 2009; Giallonardo et al., 2010) confirmed the relationship between authentic leadership and trust in coach, consistent with this result of the present study. Similar to the current study, in the study by Bandura and Kavussanu (2018) of the relationship among authentic leadership, enjoyment, and immersion, authentic leadership was mediated by autonomy and trust, which promoted the enjoyment and immersion of athletes. This result of this study is also consistent with previous studies (Bandura et al., 2016; Kim & Lee, 2019b; Kim et al., 2020; Yang, 2015) that verified the mediating effect of trust in coach. Since authentic leadership, unlike traditional forms of leadership, makes it possible to communicate with the players by acting according to the confident beliefs and personal values of the leader, it makes it easier to build trust.

These findings suggest that systematic education of and support for authentic leadership on the part of sports coaches be offered, encouraged, or even required. Future studies should investigate the effects of additional variables. Studies to date have focused on the team sports setting, so the influence of authentic leadership on individual sports should be verified. Lastly, future studies should investigate the effect of authentic leadership on player and team performance.

References

Bandura C. T., & Kavussanu, M. (2018). Authentic leadership in sport: Its relationship with athletes’ enjoyment and commitment and the mediating role of autonomy and trust. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 13(6), 174795411876824.

10.1177/1747954118768242.Carron, A. V. (1988). Group dynamics in sport. Spodym.

Carron, A. V., Hausenblas, H. A., & Eys, M. A. (2005). Group dynamics in sport. Fitness Information Technology.

Carron, A. V., Widmeyer, W. N., & Brawley, L. R. (1985). The development of an instrument to assess cohesion in sport teams: The group environment questionnaire. Journal of Sport Psychology, 7, 244-266.

10.1123/jsp.7.3.244.Chelladurai, P., & Carron, A. V. (1978). Leadership. Sociology of Sport Monograph Series Canadian Association for Health, Physical Education and Recreation.

Choe, S. H. (2020, July 9). South Korean triathlete’s suicide exposes team’s culture of abuse. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/09/world/asia/korea-triathlete-suicide.html

.Clapp-Smith, R. G., Vogelgesang, R., & Avey, J. B. (2009). Authentic leadership and positive psychological capital: The mediating role of trust at the group level of analysis. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 15(3), 27-240.

10.1177/1548051808326596.Cook, J., & Wall, T. (1980). New work attitude measures of trust, organizational commitment and personal need non-fulfilment. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 53(1), 39-52.

10.1111/j.2044-8325.1980.tb00005.x.Dayan, M., Bebedetto, C. A. D., & Colak, M. (2009). Managerial trust in new product development projects: Its antecedents and consequences. R & D Management, 39(1), 21-37.

10.1111/j.1467-9310.2008.00538.x.Deutsch, M. (1958). Trust and suspicion. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 2(4), 265-279.

10.1177/002200275800200401.Dienesch, R. M., & Liden, R. C. (1986). Leader–member exchange model of leadership: A critique and further development. The Academy of Management Review, 11(3), 618–634.

10.2307/258314.Dirks, K. T. (2000). Trust in leadership and team performance: Evidence from NCAA basketball. Journal of Applied Psychology, 83(6), 1004-1012.

10.1037/0021-9010.85.6.1004.Dirks, K. T., & Ferrin, D. L. (2002), Trust in leadership: Meta-analytic findings and implications for research and practice. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(4), 611-628.

10.1037/0021-9010.87.4.611.Gervis, M., Rhind, D., & Luzar, A. (2016). Perceptions of emotional abuse in the coach–athlete relationship in youth sport: The influence of competitive level and outcome. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 11(6), 772-779.

10.1177/1747954116676103.Giallonardo, L. M., Wong, C. A., & Iwasiw, C. L. (2010). Authentic leadership of preceptors: Predictor of new graduate nurses’ work engagement and job satisfaction. Journal of Nursing Management, 18(8), 93-103.

10.1111/j.1365-2834.2010.01126.x.Huh, J. Y. & Ma, H. Y. (2013). The mediation effect of team cohesion on between the relationship team members’ trust and team performance in pro baseball players: Using the phantom variable. Korean Society of Sport Psychology, 24(4), 155-168.

Hur, Y., Van den Berg, P. T., & Wilderom, C. P. M. (2011). Transformational leadership as a mediator between emotional intelligence and team outcomes. The Leadership Quarterly, 22(4), 591–603.

10.1016/j.leaqua.2011.05.002.Jeon, H. S. (2016). The conceptualization of athletes’ trust and the scale development [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Seoul National University.

Jeong, Y. J., & Hong, E. A. (2018). An examination of mediating role of team efficacy between coaches' authentic leadership and players' psychological well-being at girls' high school football teams. Journal of Korean Physical Education Association for Girls and Women. 32(1), 1-16.

10.16915/jkapesgw.2018.03.32.1.1.Johnson, G. C. & Swap, W. C. (1982). Measurement of specific interpersonal trust: Construction and validation of a scale to assess trust in a specific other. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 43(6), 1306-1317.

10.1037/0022-3514.43.6.1306.Kang, K. H., & Oh, K. R. (2015). The effects on team cohesion and satisfaction of university athletes by trust in leadership. The Korean Society of Sports Science, 24(6), 513-525.

Kavanagh, E., Brown, L., & Jones, I. (2017). Elite athletes' experience of coping with emotional abuse in the coach–athlete relationship. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 29(4), 402-417.

10.1080/10413200.2017.1298165.Kernis, M. H., & Goldman, M. B. (2006). A multicomponent conceptualization of authenticity: Theory and research. Advances in Experimental Psychology, 38, 283-357.

10.1016/S0065-2601(06)38006-9.Kim, M. K. (2018). Relationships among antecedents, moderators, and performance of authentic leadership [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Jeju University.

Kim, B. K., & Yoon, J. K. (2015). The mediating effects of team cohesion and team efficacy between coach’s leadership styles and team performance. The Korean Leadership Review, 6(2), 33-72.

Kim, S. H. & Lee, W. J. (2019a). The mediating effect of respect toward leaders between authentic leadership and team citizenship behavior in sport: Team-level analysis. Korean Journal of Sport Studies, 58(5), 121-136.

10.23949/kjpe.2019.07.58.5.11.Kim, S. H. & Lee, W. J. (2019b). Structural relationship among authentic leadership of sport team leaders, attitude toward leaders, job satisfaction and team commitment. Journal of Korean Physical Education Association for Girls and Women, 33(2), 91-108.

10.16915/jkapesgw.2019.6.33.2.91.Kim, J. Y, Lee, B. W, Lim, J. J. & Yoon, D. Y. (2020). The effects of authentic Leadership on innovative behavior in public institutions: The moderated mediation effect of trust in leader and promotion focus. Korean Journal of Business Administration, 33(11), 2013-2042.

10.18032/kaaba.2020.33.11.2013.Kwon, H. G. (2017). A study on the structural relationship between authentic leadership, lrust in superiors, organizational silence, turnover intention, and counterproductive work behaviors. Journal of the Korea Society Industrial Information System, 2(4), 131-147.

Kwon, S. J. & Jung, J. Y. (2016). The analysis of structural relationships among authentic leadership, trust for leaders, psychological well-being, and knowledge sharing. Knowledge Management Review, 17(4), 1-26.

Lee, D. J. & Hwang, J. H. (2016). The relationship among authentic leadership, leader trust and organizational citizenship behavior of the commercial sport center managers. The Korean Society of Sports Science, 25(5), 91-104.

Loughead, T. M., & Carron, A. V. (2004). The mediating role of cohesion in the leader behavior-satisfaction relationship. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 5, 355-371.

10.1016/S1469-0292(03)00033-5.Luthans, F., & Avolio, B. J. (2003). Authentic leadership development. In K. S. Cameron, J. E. Dutton, & R. E. Quinn (Eds.). Positive organizational scholarship: Foundations of a new discipline (pp. 241-259). Beret-Koehler.

Mardia, K. (1975). Assessment of multinormality and the robustness of Hotelling's T2 test. Applied Statistics, 24(2), 163-171.

10.2307/2346563.McMahon, J., Zehntner, C., McGannon, K. R., & Lang, M. (2020). The fast-tracking of one elite athlete swimmer into a swimming coaching role: a practice contributing to the perpetuation and recycling of abuse in sport?. European Journal for Sport and Society, 17(3), 265-284.

10.1080/16138171.2020.1792076.Moon, T. R. & Chun, S. Y. (2019). The effects of group art therapy on the communication satisfaction and group cohesion of high school soccer players. Korean Journal of Art Therapy, 26(4), 693-712.

10.35594/kata.2019.26.4.005.Park, J. Y. (2007). The relationship between competing values leadership of teacher, teacher trust, and team cohesion in school sports team [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Kangneung University.

Philippe, R. A., & Seiller, R. (2006). Closeness, co-orientation and complementarity in coach-athlete relationships. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 7, 159-171.

10.1016/j.psychsport.2005.08.004.Rousseau, D. M., Sitkin, S. B., Burt, R. S., & Camerer, C. (1998). Not so different after all: A cross-discipline view of trust. Academy of Management Review, 23(3), 393-404.

10.5465/amr.1998.926617.Song, J. (2011). SPSS/AMOS Statistical Analysis Method. 21st Century

.Walumbwa, F. O., Avolio, B. J., Gardner, W. L., Wernsing, T. S., & Peterson, S. (2008). Authentic leadership: Development and validation of a theory-based measure. Journal of Management, 34(1), 89-126.

10.1177/0149206307308913.Walumbwa, F. O., Luthans, F., Avey, J. B., & Oke, A. (2011). Authentically leading groups: The Mediating role of collective psychological capital and trust. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 32(1), 4-24.

10.1002/job.653.Wong, C. A., & Cummings, G. G. (2009). The influence of authentic leadership behaviors on trust and work outcomes of health care staff. Journal of Leadership Studies, 3(2), 6-23.

10.1002/jls.20104.Yang, G. H. (2015). The effect of authentic leadership on organizational commitment: The mediating role of leader trust. Korean Journal of Military Art and Science, 71(2), 103-133.

10.31066/kjmas.2015.71.2.005.Yang, J., & Mossholder, K. W. (2010). Examining the effects of trust in leaders: A bases-and- foci approach. The Leadership Quarterly, 21(1), 50-63

. 10.1016/j.leaqua.2009.10.004.Yukl, G. (2014). Leading in organizations (8th Ed.) Pearson.

Zand, D. E. (1972). Trust and managerial problem solving. Administrative Science Quarterly, 17(2), 229-239.

10.2307/2393957.