From the Lingerie Girls to the Legends Gladiators: Exploring Erotic Capital and Media sexualization of the LFL’s commercials

Article information

Abstract

This study explains how women’s football strategically transfers the sports league’s image from hyper-sexualized women’s sports entertainment to the real football league. By focusing on the commercial messages from the Lingerie Football League and the Legends Football League, the author could understand the nature of the sexualized culture as the unique entertainment women’s sports league. By adopting reading sport critically (McDonald & Birrell, 1999), the purpose of this study is to understand the difference between the Lingerie and Legends Football League (LFL). This study further examined how women’s erotic capital performed in the LFL. Thus, in what follows, the author explores the extent to which the LFL strategically manages the mediated athletic bodies—in terms of adornments, types of movement, and media framing—presented to its viewership. In so doing, this analysis looks at the mediated feminine body as it is transformed, made into a site for maximum erotic capital. The findings indicate how the critical perspectives explain the LFL context and provide suggestions for further exploring a newly formed women’s professional sports league.

Introduction

At the halftime show for the National Football League’s (NFL’s) Super Bowl in 2004, female models and actresses played a seven-on-seven football game in uniforms consisting of lingerie-like lacy boy-cut underwear, bras, and the minimum safety equipment for playing on a football field. This one-time show generated huge negative discourse about women’s sexualizing from women’s organizations and the mass media. However, millions of sports fans paid to watch the ‘Lingerie Bowl’ as a pay-per-view event aired on the Music Television 2 (MTV2) channel. Finally, Mitchell Mortaza, the league creator, decided to launch the Lingerie Football League (Lingerie FL) in 2009 with ten teams located in major metropolitan areas (LFL website). Thus far, the LFL has been considered a strict entertainment broadcast for pay-per-view event was appearing on MTV2 and focusing on women’s commercially sexualized images in sports. The Lingerie FL plays games in major stadiums and arenas in the prime-time period, Friday night (Daily News staff, 2008).

Interestingly, by demonstrating great popularity through the league’s economic success, the Lingerie FL has increased the number of teams globally, launching four teams in Canada since 2012 and five teams in Australia since 2013, and generated much interest among male audiences (Knapp, 2015). The league has also announced plans to establish more teams globally in Europe, Latin America, and Asia. As the league is known as a women’s American football league, it is being introduced as the nation’s fastest growing professional sports league (NBC Sports, 2013). In 2013, the Lingerie FL transformed its brand image from a lingerie-clad entertainment show to a real sporting event. Thus, the Lingerie FL announced plans to rebrand itself as the Legends Football League (Legends FL), meaning players will no longer be required to wear lingerie while playing football. The team logos will be redesigned to exclude images of sexy women, and the slogan changed from “True Fantasy Football” to “Women of the Gridiron.” Strategically, the league modified the game rules with a non-standard version of the men’s football game; the intent of the Legends FL is to eventually expand to all NFL markets (Johnson, 2009), not by threatening men’s football but by sharing the game with fans. In 2019, the Legends FL rebranded again to the Extreme Football League (X League), which announced to begin to play in April 2020. However, the newly formed X League’s first season still postponed due to the COVID-19 pandemic (www.wikipedia.com).

Judging by the tone of the LFL’s messages targeting the young adult (age from 18 to 34 years old) male audience market (Ormsby, 2009), the Lingerie FL has recognized this cultural phenomenon concerning women’s sexualization in sports and positioned itself as a solution to promote the women’s sports market. The Legends FL also provides entertainment and sexual fantasy to male spectators through the sexual promotion of women’s sports (Khomutova & Channon, 2015; Knapp, 2015; Weaving, 2014). As such, the Legends FL’s rebranding is still an ongoing issue, and they explore the new questions as to exactly how it positions female athletes within the competing paradigms of ‘soft porn’ and ‘athletic competence’ (Kane & Maxwell, 2011). Previous research to interpret the LFL (the Lingerie and Legends FL) has addressed these themes by examining external and peripheral media texts (Knapp, 2013; Khomutova & Channon, 2015), and critical and theoretical lends (Weaving, 2014; Kim & Kim, 2016). The current study explores the LFL by critically investigating its promotional media commercials.

Thus, this study aims to understand how displayed the LFL players’ gender behaviors with their erotic capital in the commercials. Further, this study examines what differences exist between the Lingerie FL and Legends FL in the commercials. This study explains the contextual explanation of female athletes depicted as sources of erotica for the women’s sports league in the commercials of the LFL. In what follows, the author expected to see the mediated feminine body as it is transformed and made into a site for maximum erotic capital.

The LFL and the sexualization of women in sport

Women’s sports and the female sporting body, particularly, but such a paradigm to work in explicating how the feminine body is objectified and made into a mode of exchange, accumulation, and commodification. Using sexualization and eroticism of athletes’ images for motivating sport spectators has also become of critical concern for scholars (Madrigal, 2006; Mutz & Meir, 2014). Thus, many scholars criticized the LFL utilized the sexualized images as their marketing strategies (Khomutova & Channon, 2015; Knapp, 2015; Weaving, 2014). They argued that media images play an important role in culture’s sexual socialization (Reichert, Childer, & Reid, 2012). That is, sex appeal can define as brand information connected with sexual information (Reichert, Heckler, & Jackson, 2001). Also, media messages reinforce sexual differences and the sexist treatment of girls and women and strengthen traditional gender roles (Murnen & Smolak, 2012). In the contemporary professional sports landscape, few entities extract commercial viability more from the marketization of “sex appeal” than the LFL (Khomutova & Channon, 2015). However, there is limited literature on research that has explored the LFL. The previous study indicated that the LFL is explicit in emphasizing its media product the sex appeal of the feminine athletic body (Frederick et al., 2017; Khomutova & Channon, 2015; Knapp, 2015; Weaving, 2014). Knapp (2015) emphasized that although the LFL has offered women an opportunity to step into the boundaries of a traditionally masculine sport (American football), female athletes’ representation remains problematic and subordinates female athletes’ role in this league. Weaving’s (2014) study helped understand the doping and socio-cultural issues such as mal-behaviors and ethical acceptability of players and sports leagues.

Moreover, in Khomutova and Channon’s (2015) study, they utilized a mixed-methods approach that combined content and semiotic analysis to understand the messages within the LFL. They examined sexuality, athleticism, and their leagues’ symbolic construction of women’s sporting femininity. By exploring the social media content of the LFL, Frederick and colleagues (2017) found that the Facebook page of the LFL focused on the problematic dual ideal of sexualized with masculine athletes. By focusing on the commercial messages, Kim and Kim (2016) analyzed the season’s commercial narrative of the Legends Football League (Legends FL) to capture the sexualized women’s sport league’s cultural meaning. This study interpreted the selected commercials of the Legends FL the meaning by reading critically. They found that the Legends FL framed to a greater degree in ‘player-focus views’ than ‘event-focus views’ and ‘court-/field-focus views’ in the national commercials. These player-focus views of media frames intentionally led audiences to concentrate on the Legends FL players’ body by highlighting visual images and active movements. Thus, all previous literature calls to question ironic images of the LFL that has a masculine image but still sexualized women’s sports league.

Erotic Capital as a Resource in Women’s Sports

From sociology, Pierre Bourdieu’s theories of capital (social, cultural, physical) gave life to a new approach for exploring how individuals and communities come to embody social class interactively. These are but three examples of seeking to apply the logics of aggregation and exchange to explore how non-monetary aspects of social life (education, friendships, cultural experiences, and physical body) can be turned into more traditional capital (money, assets, etc.). The individual’s ability to accumulate and exchange various forms of non-economic capital is of central concern for many scholars within the social sciences.

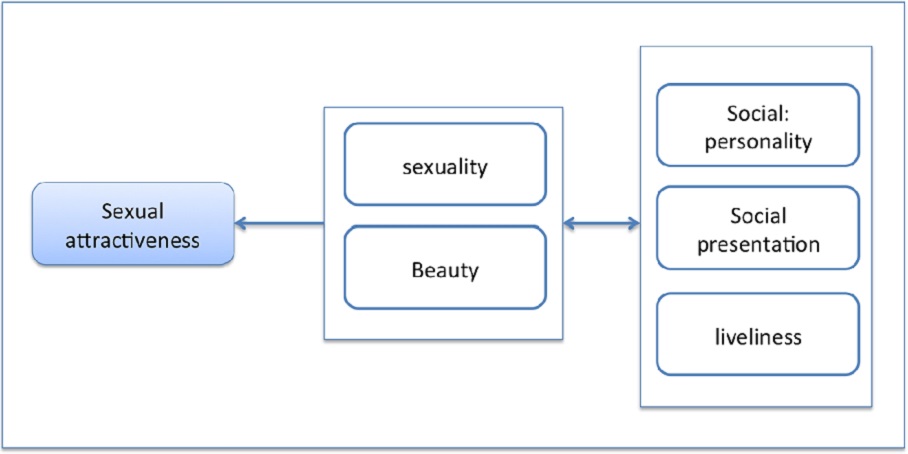

The social and economic value of erotic capital emphasized in what can broadly described as the entertainment and sports industry. Erotic capital considered a fourth “asset” but an equally important and relevant form of capital ancillary to economic, cultural, and social capital (Hakim, 2010). Specifically, the concept of erotic capital comprises six elements of beauty, sexual attractiveness, social skills, liveliness, social presentation, and sexuality. The first element, beauty is central to erotic capital, symmetry and clear skin tone might contribute to an attractive other (Webster & Driskell, 1983). Despite this general connection to beauty, it is also important to note that there are cultural and temporal variations regarding what constitutes beauty (Webster & Driskell, 1983). The second element is sexual attractiveness (Hakim, 2010). Beauty is generally about facial attractiveness, while sexual attractiveness is more about the body. However, sexual attractiveness also includes factors such as personality and style and many different social constructions such as femininity or masculinity.

The other three elements of erotic capital were not directly related to physical traits. The third element of erotic capital is social skills such as grace, charm, social interaction skills, the ability to make people like you, feel at ease and happy, want to know you, where relevant, and desire you. Social skills also relate to a ‘what is beautiful is good’ stereotype that examined in previous social psychological research (Dion, Berscheid, & Walster, 1972; Feingold, 1992; Langlois et al., 2000). These studies found that physical attractiveness reflected in social skills such as being intelligent, mentally healthy, and likable. The fourth element of erotic capital is liveliness, a mixture of physical fitness, social energy, and good humor. According to the theory, people who have much life in them are attractive to others- as illustrated by people who are ‘the life and soul of the party.’ In most cultures, liveliness can display in dancing skills or sporting activities. This element can be the most relevant in taking advantage of sporting women. The fifth element is social presentation. This element includes the style of dress, makeup, perfume, jewelry or other adornments, hairstyles, and various accessories that people carry or wear to show their social status and style to the world (Hakim, 2010). The sixth element is sexuality itself: sexual competence, energy, erotic imagination, playfulness, and everything else that makes for a sexually satisfying partner (Green, 2008; Hakim, 2010). Erotic capital is a combination of aesthetic, visual, physical, sexual attractiveness to other members of the opposite sex in all-social contexts, including sport. Thus, the primary argument is that women could learn and develop erotic capital.

Erotic capital used to investigate beauty-related business, entertainment industry, service economies such as sale work and managerial positions, and career image development for job searching (e.g., Frew & McGillivray, 2005; Hooley & Yates, 2014, Mears, 2014). For many scholars, erotic capital is performed and developed by consumers by centrally intertwining with consumption (Sarpila, 2013). For example, beauty, sexual attractiveness, and social presentation could perform and develop through appearance-related consumption such as the style of clothing and the use of accessories, makeup, and hairstyling (Sarpila, 2013). In a consumer culture, beauty-related consumption plays a crucial role in making beautiful and attractive people to others.

In sport context, the case often made that physically attractive athletes—for example, Maria Sharapova, Ana Ivanovic (tennis players)—have achieved high economic capital (e.g. high salaries and lucrative endorsement deals). She possesses high popularity—to some degree due to the valorization of their erotic capital. Thus, erotic capital that especially highlighted on the importance of beauty and sexual attractiveness of body has also been utilized to investigate sport celebrities who are sexy and popular (Chawansky & Francombe, 2013; Mutz & Meier, 2014). In many instances’ women are just seeking to play sports, and patriarchal media and professional sport intermediaries seek to transform sport performance and sporting bodies into accumulation and exchange of erotic capital (Chawansky & Francombe, 2013).

In seeking to maximize erotic capital in women’s sports, one could make the case that executives and administrators exploit female athletes to offer potential sponsors an additional benefit, namely a sexually attractive body fitting into societies’ beauty standards. It may be perceived as a unique selling point. Researchers have shown that athletic performance combined with physical attractiveness is the most important factor defining athletes’ desirability as endorsers (e.g., Cunningham et al, 2008; Fink et al, 2004, Fink et al, 2012).

Previous literature argued that commercialized professional sports business is an essential site for examining erotic capital debates (Kim & Kim, 2016; Mutz & Meier, 2014; Meier & Konjer, 2015). To examine the connection between popularity and income of high-performance athletes, Mutz and Meier (2014) investigated the relationship between public attention and the physical attractiveness of soccer players. Interestingly, they found that soccer players’ physical attractiveness was salient factor to increase public interest of sport fans and this popularity led to generate more income to the players. Thus, erotic capital enhanced public interest, and popularity was essential to generate income. The mediated and commercialized professional sports seek extra erotic attraction from athletes to increase public attention for sports fans. The public interest plays a crucial role in the transformation of erotic capital into economic capital.

The overview of the current study

This study extends this conjoint line of inquiry by drawing upon theory of ‘erotic capital’ to explicate how the mediated female football player managed toward commercial ends (Agthe et al., 2011; Eagly et al., 1991). While previous studies initially address the issues of the LFL (Lingerie and Legends Football League) within the sports literature (Frederick et al., 2017; Khomutova & Channon, 2015; Kim & Kim, 2016; Knapp, 2015; Weaving, 2014), several questions regarding the sexualization of women’s sport within this context not answered. The current study contributes to sports literature by applying multi-layered methodologies to understand the cultural meanings of the sexualization of women’s sports league from the commercial narratives. By comparing the Lingerie and Legends Football League commercials, First, the current study gives unique insights to understand how gender display of LFL players in the commercials play a role in reforming the LFL images. Further, this study also looks at a theoretical explanation of how female athletes are depicted as sources of erotic capital for the women’s sports league through critical reading a sports context.

The proposed research question guiding the analysis are 1) How do gender behaviors of the LFL players displayed in the LFL commercials? 2) What differences exist in performing erotic capital between the Lingerie FL and the Legends FL in the commercials?

Method

Research design

In introducing the ‘reading sport critically’ method, McDonald and Birrell (1999) stated that in the stories of sports celebrities, or heroes, individuals become repositioned for political narratives; “they also task as cultural critique is not for the fact of their life but to search for how those ‘facts’ constructed, framed, obscured and forgotten” (p. 292). Thus, the ‘reading sport critically’ method helps examine power dynamics in sport by using a person or event as the research text (McDonald & Birrell, 1999; Knapp, 2015; Kim & Kim, 2016). Moreover, McDonald and Birrell further stated that research could capture how the ideological work formulated through such framing. To understand women’s sexualization in sport, using both dominant narratives of the LFL commercials and the hidden meanings, this study significantly contributed to larger cultural meaning in the sport context (McDonald & Birrell, 1999; Knapp, 2015). Thus, the authors critically read the context of the commercials and qualitatively examined the LFL as texts, with attention to representations of gendered portrayals in women’s sports leagues and how media presented erotic capital of female athletes in the sexualized sports images. In addition, this critical reading method for special commercials was also studied by Lucas (2000); that article interpreted the cultural meaning of NIKE’s commercial more closely against the NIKE’s history and its cultural background and then offered the researchers’ evaluation from a critical perspective.

Data Selection

By having 287K subscribers (Feb 2021) on the YouTube official channel of the X League (former the LFL), the LFL has the explosive international popularity of women’s football. The representative public images for the Lingerie Football League (Figure 1) and the Legends Football League (Figure 2) were presented by Google search, this study focuses on the promotional contents only to capture the underlined commercial message of the LFL. Thus, presented a promotional films and each season’s national commercial was the optimal choice to represent the league images. After collecting the data with rebranding as Legends Football League, 13 videos from ten years’ seasons finally selected for this study. Here is the selection of the 10 seasons from 2009 to 2018. These videos were selected and watched from the LFL official channel’s promotional content list on YouTube. These videos mostly represented the image of the LFL effectively as a promotional content. Six selected commercial films of the Lingerie Football League were 2009 season 1 teaser Promo, 2009 Game changer commercial, 2010 season 2 teaser, 2011 season 3 teaser: The huddle, 2011 Lingerie bowl commercial, and 2012 Lingerie bowl commercial (extended directors). After rebranding, seven The Legends Football League films selected from: 2013 The beginning, 2013 USA. National commercial, 2014 The story teaser: fight until the final whistle, 2015 National commercial, 2016 National commercial, 2017 Legends Cup: Judgment Day, 2018 Legends Cup promo.

Epistemological Position and Data Analysis

In terms of analyzing the data, the author qualitatively and critically examined the LFL (the Lingerie and Legends Football League) commercial narratives as texts, analyzing gender display with attention to representations of performed erotic capital in the promotional films. The author carefully analyzed commercial messages by repeatedly watching films with attention to representations of how the players performing erotic capital in the promotional films. Then, the analysis sequence moves to the second level framework by applying critical reading. As a researcher, the author followed a constructivist-interpretivist paradigm, such that the author sought to better cognize the cultural meanings of social context, media messages, attitudes of media audiences, and lived experiences (Ponterotto, 2005; Cunningham, 2015). In adopting this position, the author highlights and seeks a rich description to the commercial messages with relevant theories and resources. As a researcher, the author continuously updates interest in women’s sports and conducted several research to strengthen the critical perspective to interpret the social messages toward women’s sport context.

Gender display. The author investigated how the gender of female athletes performed in women’s football. To understand the constructed gender behaviors in theses media outlet, Goffman’s (1976) ‘gender display’ and other relevant studies regarding gender portrayals in the media utilized as a benchmark for analysis in the current study. Previous research on gender display included feminine behaviors or facial expressions with smiling, hair touching, childish finger to/in the mouth, a sultry look, and a withdrawn gaze (e.g., Belknap & Leonard, 1991; Goffman, 1976; Kang, 1997; Signorielli et al., 1994).

In this study, gender display divided into mainly two categories, feminine values, and masculine values. The feminine/sexual value category included smiling, touching the hair, displaying a childish finger to/in the mouth, showing a sultry look, and dancing. These categories originally modified from Wallis’ (2011) music video analysis. Many music videos’ themes are related to gender stereotypical portrayals, such as sexually suggestive postures by female singers and aggressive behaviors by male singers (Cummins, 2007; Gow, 1990; 1996; Wallis, 2011). These gendered behaviors, such as hand gestures, body poses, verbal expression, and facial expressions as main categories, included to analyze female athletes’ gendered display in the women’s sport (Kim & Sagas, 2014). Furthermore, feminine value categories addressed by Goffman’s (1976) gender display and Kang’s (1997) concept of female body display. This category included feminine touch, ritualization of subordination, and licensed withdrawal. This feminine value also included overly sexual expressions such as a sultry look and dancing. This study added two categories based on the development data analysis procedure: makeup/dress up and wearing sexualized uniform or equipment as social, personal presentation to capture gendered women’s entire image in the LFL.

In the major categories of masculine value, to capture the aggressive behaviors in women’s sports, gender display categories included showing masculine, passionate playing during games. Also, aggressive looks and shouting added from the development data coding procedure. For the LFL videos in particular, verbal expressions, swaggering and taunting, talking, and celebrating categories were analyzed in this study. In the sport context, female athletes have been portrayed in sexually suggestive poses in mainstream media and like other women (e.g., Daniel, 2009; Daniel, 2012; Kane et al., 2013). It was necessary to consider how women’s sports reveal their images within media frames and interpret these images in the gendered display within the social context.

Procedures

This study collected data from a variety of sources for validation. First, this study conducted a critical reading method for methodological triangulation with qualitative analysis for the promotional videos of the LFL. This study gathered other data sources for critical reading the cultural messages. These include (a) information from the LFL related news, magazines, and blog information more broadly, (b) external publications, such as articles written in academic literature. Finally, the researchers also kept a reflexive journal to track authors’ personal observations during the research process. For improving the credibility and trustworthiness of the finding, this study used an expert check, such as discussion with critical feedback from sport media experts.

Results

Performing gender and erotic capital

This study critically and qualitatively examined the commercial content from the Lingerie Football to the Legends Football as research texts, focusing on representations of how the players performing erotic capital, especially within the gendered behaviors as the social context. The two significant subjects which featured in the promotional films were definitely (a) the game moments on highlights and (b) players’ faces and body postures of the LFL. As a mixture of the game moments and the players’ focused camera frames, the most representative commercial narrative was ‘sexualized body poses’, ‘seductive facial expression’, ‘aggressive behaviors (playing, fighting)’, ‘aggressive looks (serious facial expression, no smiling)’, and skimpy outfits (uniforms). Regardless of the main themes of each league, the Lingerie Football League was overwhelmingly focused on the players themselves, such as her facial expressions and specific body parts, poses rather than the game highlights or overall sports image as a women’s football. In the 2009 season and 2010 season 2, the sexualized body poses and seductive facial expressions in the early commercial were dominant themes for gathering new sport audiences. The viewers were always exposure to the players’ sexy body by wearing the skimpy outfits (uniforms). However, the Legends Football League-rebranded from the Lingerie Football League, definitely focus on the gladiator looks of players with masculine image as football players, and then displayed them in much more on game highlights and show spectacle moments of game itself. The Legends Football League’s commercial also mainly displayed athletic but sexy type players by showing aggressive looks (facial expression), aggressive behaviors in skimpy outfits (uniform).

In the first season of the Lingerie Football League, their commercial films focused on the player’s facial expressions and body postures. Thus, the media viewers easily captured the highlighted player performing erotic capital by showing her beauty and sexual attractiveness from the players’ fit body. Social presentation such as heavy makeup and hairstyling could also capture in promotional films. These images lead to captivating the viewers’ perspective on the players’ beauty, sexual attractiveness, and social presentation. On the other hand, the Legends Football League also highlighted the players’ the masculine images with aggressive facial expression and behaviors such as pushing the other players and shouting. Although the commercial focused on the player, they created a different image in the Legends Football League than the Lingerie Football League. Also, the Legends Football League also mostly captured the game highlight on the liveliness of performing erotic capital. While watching the game highlights, the media viewer followed players’ movements that showed their liveliness than the static element of the players. However, the most problematic issue was their inappropriate outfit for a football play. The viewers must pay attention to the player and their uniforms to watch the commercial films. Thus, if this uniform was sexualized, the overall images of the LFL generated criticism from the general viewers.

The Lingerie Football League was mainly focused on portraying feminine images by highlighting faces and suggestive body postures of players. However, the Legends Football League presented very masculine images of the athletes, and each scene rarely captured feminine hand gestures and body poses in terms of gender behaviors (Goffman, 1979). Additionally, as the early rebranded league’s commercials, the Legends Football League keep sending messages that the players are ready to play real contact football with great athleticism and aggressiveness by removing the previously framed the sexualized images of the Lingerie Football League.

The Legends Football League’s national commercial films mostly utilized many views that portrayed interpretable gendered behaviors through the game highlights. To critically read the commercial narrative, this study carefully analyzed the players’ facial expressions and body gestures to see if they perform their erotic capital. In particular, the facial expressions of the athletes were mostly aggressive to the opposite team. There were no feminine looks such as smiling that assumed as a traditional gender norm. The interpretable message from the facial expression means that they not focused on what is beautiful is good’ (Dion, Berscheid, & Walster, 1972). Body postures also included passionate and aggressive playing, shouting, and celebrating the goals that were mostly related to sport-focused behaviors that were not directly performed erotic capital, and sexual attractiveness.

However, there are few positive social skills performed. In showing the social skill such as being nice to people, being likable, the athletes and coaches complained about the results of games, violation and captured many fights against other teams of athletes during the game highlight moments. Furthermore, personal presentation such as uniforms and makeup of players may invite more audiences to see them as sexualized images of women in the field or arouse some sexual fantasy within the sexualized sports culture in the Western society. However, although the Legends Football League rebranded from the Lingerie Football League, their images still criticized women’s sport images (Frederick et al, 2017; Knapp, 2015).

Discussion

This study applies erotic capital theory as a framework to better understand the commercialized women’s sport nature with a case of the LFL. This study critically examined how women’s sporting bodies are managed and transformed into sites to accumulate erotic capital. By focusing on female athletes’ faces in the promotional films, beauty was central element for the LFL players. This result is consistent with Weaving’s (2014) study that the LFL marketers tried to hire the players who were mostly white, blonds, and physically gorgeous women such as former models. This study further explicates that sexual attractiveness should be a central element of the LFL players. They mainly showed that hard training, fitness, and football should shape a sexy body of female athletes throughout the promotional videos. Well-developed and slim bodies of female athletes should be sexually attractive to men, so they performed great deals of erotic capital. Some goal ceremonies and body gestures of the LFL players in the highlighted videos were sexually symbolized and may arouse sexual fantasy. This consisted of previous studies (Khomutora & Channon, 2015; Knapp, 2015; Weaving, 2014) that the LFL included some messages related with sexual fantasy to men using images of body poses and facial expressions of women in their commercial videos.

Thus, a major finding is that the Lingerie Football League players took advantage of their beauty, sexual attractiveness, and sexuality, which were core elements of erotic capital. There were some pieces of evidence that they intentionally presented sexual imaginary of the LFL players wearing lingerie-like uniforms and heavy makeup in the early commercials. Thus, mainly performed elements of erotic capital of the LFL players were beauty, sexual attractiveness, and sexuality than other elements such as social, social presentation, and liveliness. Not surprisingly, the major hiring point of the LFL players was their beauty and attractiveness (Khomutova & Channon, 2015; Mutz & Meir, 2014). Thus, secondary qualification was their athletic ability to support sexual attractiveness for their marketability of the league. This means that sexual attractiveness, beauty, and sexuality were essential elements of erotic capital for the LFL players. In addition, the LFL players effectively presented the sexualized image of women’s bodies with performance gears, makeup, and hairstyle. These presentations related to developing their social presentation element of erotic capital. Female athletes were portrayed as feminized women with heavy makeup and enhanced their feminine looks in the football field. Social presentations of them support to develop of their sexual attractiveness finally.

Another significant finding of performing erotic capital analysis is that female athlete in the Legends Football League mostly displayed as overly masculine by showing aggressive behaviors such as shouting and fighting with opposite team players. This result means that they mainly highlighted performing liveliness of the players as part of performing erotic capital than other elements such as beauty and sexual attractiveness. This finding was distinct from previous research findings mostly about female athletes’ feminine portrayals in sports settings (Kolnes, 1995; Krane et al., 2004; Kane et al., 2011). Thus, the finding is valuable to fill the gap which lack of masculine images in women’s sports in the extant literature (Duncan, 1990). In particular, aggressive looks, shouting, and the showing of masculine behaviors addressed how female athletes project masculinity in women. Interestingly, sports media reinforces masculine hegemony in society by reflecting societal attitudes that are negative toward female athletes, particularly those who compete in what has historically been considered masculine sports, especially football (e.g., Urquhart & Crossman, 1999; Vincent et al., 2003).

As shown in the LFL context, commercialized women’s sport is no longer to concerned with athleticism alone, instead, carefully maneuvering marketability of them by adding the commercial value through the sexualized body for business success. This finding also supported the interesting finding from Khomutova and Channon’s study (2015) that the LFL’s vision of women’s sport was targeted as being produced by men and for men. Additionally, Messner (2002) also mentioned that the male privilege occupied the clear and center value of sexualizing female sporting bodies in women’s sport. It is worth looking into how the LFL strategically managed commercial videos to produce eroticism for women’s sport and how they transformed female bodies into sites for the accumulation of erotic capital in women’s sport. Erotic capital is a practical framework to investigate the commercialized women’s sport and explains why the LFL presented the sexualized image as the main focus even in the rebranding as the Legends Football League. It fits into the needs for business-oriented and male-centered ideas for male spectators. This study manifested the sporting bodies were problematically presented again in these media products and reinforced gendered behaviors and hierarchy in sport business.

Implication, Limitations, and Suggestions for the Future Studies

Implications

For theoretical implication, this study supported previous research, concluding that sexualized images exist in the sports context through multi-layered critical analyses of the LFL promotional videos. These empirical findings extend our understanding of female athletes’ current representation in sports media by applying the erotic capital (Hakim, 2010). This study may present a new conceptual model to understand the sexualized women’s port and give some useful suggestions to develop athletes’ erotic capital to promote women’s sport. To develop the erotic capital of female athletes, they may focus on their beauty, sexuality, and sexual attractiveness to attract other genders. However, there are also alternative ways to develop erotic capital, such as social skills, liveliness, and social presentation. These are much more balanced development for both genders by developing sport identity because erotic capital is not equally developed by gender. Sometimes, it is reversed by gender.

As shown in the proposed conceptual model (see Figure 3), erotic capital accumulation is constrained as it is dependent on the other types and volumes of capital an agent may possess (Spaaij, 2009; Kitchin & Howe, 2013). Hence if individuals lack economic, a cultural capital, or social capital, they are limited to enhance their erotic capital. For example, highly successful athletes without erotic capital may limit to increase their social capital such as social status, fame, and popularity. For example, Anna Kournikova, who considered as a sex symbol instead of a tennis professional, may have high social capital because of their erotic capital. Furthermore, athletes’ erotic capital led to enhance their economic capital (economic benefits) because of their increased social capital (fame, popularity). Thus, erotic capital could be replaced with other capital forms to develop a greater critical awareness of its impact on the sport. Previous scholars mentioned that Bourdieu’s social capital has been examined as a relational construct in related to other forms of capital. Spaaij (2009) also examined the interplay between economic, social, and cultural capital in sport. According to previous studies’ findings, niche areas for new research to demonstrate how the sport developed economic and cultural capital was lacking and how these capitals closely inter-related with erotic capital in sport.

Thus, this study proposed new conceptual model with a new capital, erotic capital, by conducting multi-layered analyses of the LFL promotional videos to understand the sexualized women’s sport context (see Figure 3). By closely reviewing major elements of erotic capital at micro-level, this study found some valuable niche research areas that deeply investigated social theory about “capital” in sport context. The erotic capital of athletes might have enough values to add as a new capital in a sport context. There are still many areas to research with social capital to understand sport leagues issues. It will expand the rich understanding of the current trend of erotic portrayals in sport management field. Also, a relational use of Bourdieu’s social theory poses many potential benefits for sport management. This relational approach using Bourdieu’s social theory and Hakim’s erotic capital provides a fundamental conceptual model for examining sport management phenomena (Kitchin & Howe, 2013). This should further understand imbalanced portrayals of gender in sports and sexualization of women and develop a more critical explanation about these issues in sport management.

For managerial implication, this study shows that looking at sport marketers’ attitudes and from a sport spectator culture perspective helps explain how people see the meaning of performing erotic capital. To promote women’s sports league, this study suggested developing athleticism as the first value, they increase the same part of erotic capital such as social skills (interview skills, confidence, good manners to audiences) and social presentation (well-dressed on off-court) rather than highlighting beauty, sexuality, and sexual attractiveness (Sarpila, 2013; Mutz & Meier, 2014). For example, developed and well-constructed interview skills of the LFL athletes and coaches will enhance the fan-engagement level and communicate with sports organizations and reporters. That is, the communication skills of the LFL will develop the fandom. More recent days, athletes’ value such as confidence, attitudes, social kindness is important value to sports fans. The LFL could highlight developing this. Especially off-field, the League could find a variety of ways to show their holistic and well-developed erotic capital such as personality, social skill, and social presentation (athletes’ life-style, social activities). To maximize the marketable value of attractive sporting women in the commercialized sport, social skills and social presentations from erotic capital might be useful to female athletes. Thus, this study should be giving some practical ideas to promote women’s sports with erotic capital.

Also, the LFL is a unique case to understand how to make a new brand image in the promotional content through the social media platform because the Lingerie Football League rebranded itself as the Legends Football League to change the previous league brand images. This research has found that branding remains an essential component of a newly formed professional sports league’s marketing and commercial activities. The roles that star players, coaches, and outstanding managers need to make history for the rebranded sports league. For example, the previous study already proved that branding activities are well-established. Therefore, this study suggested that making a new brand image, symbol, slogan, and other assets should remain a crucial part of the professional sports league branding and marketing (Anagnostopoulos et al., 2018). There is no doubt that the proliferation of digital technologies, allied to the glowing and now ubiquitous use of social media, is challenging the parameters of existing branding activities among sports leagues (Anagnostopoulos et al., 2018). Sport managers need to learn with the emerging branding and communication skills.

Limitations and Suggestions for the Future Studies

Although this study has provided empirical evidence and insights into understanding the sexualized view toward the unique women’s sports league, some limitations should consider. The first limitation is related to the sample used in this study. Although empirical evidence was collected to meet the purpose of this study adequately, there are many other types of videos for the LFL. Also, the LFL might not be representative of traditional women’s sports images as the LFL often viewed as an “entertainment” rather than a traditional “sport.” Future research might explore various women’s sports’ brand images such as the WNBA (Women’s National Basketball Association), LPGA (Ladies Professional Golf Association), and WTA (Women’s Tennis Association). Hence, the findings’ generalizability could improve by using broader and more comprehensive sampling frames in similar media outlets framing for future studies.

Another possible limitation of this study is the use of critical reading of commercial narratives. It might not be sufficient to understand the women’s sports league thoroughly. The future research could conduct the experimental design study, qualitative interviews with female athletes, in-depth interviews, or focus groups (i.e., customers, athletes, media editors or managers, sports agencies). The future study might need experts’ discussions about the sexualization of women and measure enjoyment of sexualization in sport (Pellizzer, Tiggemann, & Clark, 2016). Finally, future research can examine the LFL players’ self-perceptions or coaches and marketers’ perspectives regarding this issue and their attitudes toward developing and performing erotic capital for their sport. This critical reading method would allow for a more comprehensive understanding of the shifts in representation and persistent trends of women’s sports images over time.

Conclusion

This theoretical analysis gives some cultural background to explain why the LFL players performed gender in sexual ways while performing masculine behaviors. Before rebranded as the Legends Football League, the Lingerie Football League might take advantage of female athletes’ eroticism that mostly included white beauty and sexualized images of bodies in the western society for their league economic success by targeting male audiences (Kim & Sagas, 2014; Kim & Kim, 2016). This is not only about how the LFL takes advantage of their erotic capital, but it is also how their erotic capital transforms into their economic capital with successful women’s sports league known as a fast-growing women’s professional leagues globally. As clear evidence, the league creator and acting commissioner Mortaza stated that “not only are the LFL players beautiful, but they are athletic. That is the ‘wow’ factor there (Shafer, 2009).” This is directly related to the beauty, sexual attractiveness of gorgeous women, and different social skills with confidence, and some liveliness for athleticism. Based on their comments on the LFL they are looking for the right mix of sexy hot girls who are sexually attractive women rather than an athlete. As shown in the economic success of this league, the LFL plays games in major stadiums and arenas in the prime-time period, Friday night. However, most Women’s Football Alliance (WFA) and Independent Women’s Football League (IWFL) games are played on high school fields, and the teams also struggle to find sponsors and capture media attention; they are generally ignored by the mainstream media and audiences (Knapp, 2015).

However, as shown in significant findings from performing erotic capital of this study, the Legends Football League promotional films mainly focused on their masculine images as athletes by showing aggressiveness playing with inserts diversified game highlighted views. Thus, their athleticism can be a great tool to develop their erotic capital in their sport fully. The LFL players could get attention from the audiences because of their football skills. That is, showing the masculine images, just doing sport, is the best way to interact with their fans and succeed in rebranding by developing rapport with them by sharing similar feelings through watching sports. This study takes effort to reveal how the LFL rebrand the brand image of the sexualized women to masculine athletes by making in the commercial films of each season. Therefore, this study envisages that the present study’s insights will provide a much-needed access point into the discussions on brand management enhancement through social media in the context of professional women’s sport league.

Furthermore, the authors argue that we need to further effort to recognize the value of sporting female bodies who is energetic and joyful in sports activities (Newman, 2014) and critical aspects for sport business to exclude sexualized images of women for only business. Also, in the time of the rise of pretty and powerful sporting women as a cultural icon, sports media may need to find a new rule for a new time for sporting women who are physically healthy and feminine instead of defined female athlete who is considered dual identity as athlete and women (Bruce, 2015). The critical line of previous studies extended to understand the socially gendered context (e.g., Fink et al., 2012; Kane & Maxwell, 2011; Kane et al., 2013; Yoder, 2016). Future researchers further need to examine how erotic capital is embedded in sport and how we can utilize it in positive ways by maximizing the sporting body’s value without the sexually-focused body image for women’s sport.

References

Agthe, M., Spörrle, M., & Maner, J. K. (2011). Does being attractive always help? Positive and negative effects of attractiveness on social decision making. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 37, 1042-1054.

10.1177/0146167211410355.Anagnostopoulos, C., Parganas, P., Chadwick, S., & Fenton, A. (2018). Branding in pictures: using Instagram as a brand management tool in professional team sport organisations. European Sport Management Quarterly, 18(4), 413-438.

10.1080/16184742.2017.1410202.Becker, G. S. (1971). The economics of discrimination. 2nd edition. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

10.7208/chicago/9780226041049.001.0001.Belknap, P., & Leonard II, W. M. (1991). A conceptual replication and extension of Erving Goffman's study of gender advertisements. Sex Roles, 25(3-4), 103-118.

10.1007/BF00289848.Bruce, T. (2015). New rule for new time: Sportswomen and media representation in the Third Wave. Sex Roles.

10.1007/s11199-015-0497-6.Chawansky, M., & Francombe, J. (2013). Wanting to be Anna: examining lesbian sporting celebrity on The L Word. Journal of Lesbian Studies, 17(2), 134-149.

10.1080/10894160.2012.664100.Cummins, R. G. (2007). Selling music with sex: The content and effects of sex in music videos on viewer enjoyment. Journal of Promotion Management, 13, 95–109.

10.1300/J057v13n01_07.Cunningham, G. B. (2015). Creating and sustaining workplace cultures supportive of LGBT employees in college athletics. Journal of Sport Management, 29(4), 426-442.

10.1123/jsm.2014-0135.Cunningham, G. B., Fink, J. S., & Kenix, L. S. (2008). Choosing an endorser for a women’s sporting event: The interaction of attractiveness and expertise. Sex Roles, 58, 371-378.

10.1007/s11199-007-9340-z.Daniels, E. A. (2009). Sex objects, athletes, and sexy athletes: How media representations of women athletes can impact adolescent girls and college women. Journal of Adolescent Research, 24(4), 339-422.

10.1177/0743558409336748.Daniel. E. A. (2012). Sexy versus strong: What girls and women think of female athletes. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 33, 79-90.

10.1016/j.appdev.2011.12.002.Daily News staff (October 8th, 2008). Putting the skin in pigskin, Lingerie Football League to debut in 2009. Available at http://www.nydailynews.com/sports/2008/10/08/2008-10-08_putting_the_skin_in_pigskin_lingerie_foo.html#ixzz0Un9rLhDh

.Dion, K., Berscheid, E., & Walster, E. (1972). What is beautiful is good. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 24(3), 207-213.

10.1037/h0033731.Duncan, M. C. (1990). Sports photographs and sexual difference: Images of women and men in the 1984 and 1988 Olympic Games. Sociology of sport journal, 7(1), 22-43.

10.1123/ssj.7.1.22.Eagly, A. H., Ashmore, R. D., Makhijani, M. G., & Longo, L. C. (1991). What is beautiful is good, but…: A meta-analytic review of research on the physical attractiveness stereotype. Psychological Bulletin, 110(1), 109-128.

10.1037/0033-2909.110.1.109.Feingold, A. (1992). Good-looking people are not what we think. Psychological Bulletin, 111(2), 304-341.

10.1037/0033-2909.111.2.304.Fink, J. S., Cunningham, G. B., & Kensicki, L. J. (2004). Using athletes as endorsers to sell women’s sport: Attractiveness versus expertise. Journal of Sport Management, 18, 350-367.

10.1123/jsm.18.4.350.Fink, J. S., Parker, H. M., Cunningham, G. B., & Cuneen, J. (2012). Female athlete endorsers: Determinants of effectiveness. Sport Management Review, 15(1),13-22.

10.1016/j.smr.2011.01.003.Frederick Jr, E. L., Pegoraro, A., & Burch, L. M. (2017). Legends worthy of lament: An analysis of self-presentation and user framing on the Legends Football League’s Facebook page. Journal of Sports Media, 12(1), 169-190.

10.1353/jsm.2017.0007.Frew, M., & McGillivray, D. (2005). Health clubs and body politics: Aesthetics and the quest for physical capital. Leisure Studies, 24(2), 161-175.

10.1080/0261436042000300432.Glenny, E. G. (2006). Visual culture and the world of sport. The Scholar & Feminist Online, 4(3). 4.

Goffman, E. (1979). Gender advertisements. New York: Harper & Row.

Gow, J. (1990). The relationship between violent and sexual images and the popularity of music videos. Popular Music & Society, 14(4), 1–10.

10.1080/03007769008591409.Green, A. I. (2008). The Social Organization of Desire: The Sexual Fields Approach. Sociological Theory, 26(1), 25-50.

10.1111/j.1467-9558.2008.00317.x.Hakim, C. (2010). Erotic capital. European Sociological Review, 26(5), 499-518.

10.1093/esr/jcq014.Hooley, T., & Yates, J. (2014). ‘If you look the part you’ll get the job’: should career professionals help clients to enhance their career image?. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 1-14.

10.1080/03069885.2014.975676.Kane, M. J., LaVoi, N. M., & Fink, J. S. (2013). Exploring elite female athletes’ interpretations of sport media images: A window into the construction of social identity and “selling sex” in women’s sports. Communication & Sport, 1, 269-298.

10.1177/2167479512473585.Kane, M. J. & Maxwell, H. D. (2011). Expanding the boundaries of sport media research: Using critical theory to explore consumer responses to representations of women’s sports. Journal of Sport Management, 25, 202-216.

10.1123/jsm.25.3.202.Kane, M. J., LaVoi, N. M., & Fink, J. S. (2013). Exploring elite female athletes’ interpretations of sport media images: A window into the construction of social identity and ‘‘selling sex’’ in women’s sports. Communication & Sport, 1(3), 269-298.

10.1177/2167479512473585.Kang, M.-E. (1997). The portrayal of women’s images in magazine advertisements: Goffman’s gender analysis revisited. Sex Roles, 37(11/12), 979-996.

10.1007/BF02936350.Khomutova, A., & Channon, A. (2015). ‘Legends’ in ‘lingerie’: sexuality and athleticism in the 2013 Legends Football League UUSseason. Sociology of Sport Journal, 32(2). 161-182.

10.1123/ssj.2014-0054.Kim, K., & Sagas, M. (2014). Athletic or sexy? A comparison of female athletes and fashion models in Sports Illustrated swimsuit issues. Gender Issues, 31(2), 123-141.

10.1007/s12147-014-9121-2.Kim, K, & Kim, Y. (2016). The commercialism and sexualization of women in sports: The critical reading of Legends Football League national commercials. Korean Journal of Sociology of Sport. 29(3). 89-113.

10.22173/jksss.2016.29.4.89.Knapp, B. A. (2015). Garters on the gridiron: A critical reading of the lingerie football league. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 50(2), 141-160.

10.1177/1012690212475244.Kolnes, L. J. (1995). Heterosexuality as an organizing principle in women’s sport. International Review for Sociology of Sport, 30, 61-77.

10.1177/101269029503000104.Krane, V., Choi, P. Y. L., Baird, S. M., Aimar, C. M., & Kauer, K. J. (2004). Living the paradox: Female athletes negotiate femininity and masculinity. Sex Roles, 50, 315-330.

10.1023/B:SERS.0000018888.48437.4f.Lucas, S. (2000). Nike's commercial solution: Girls, sneakers, and salvation. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 35(2), 149-164.

10.1177/101269000035002002.Langlois, J. H., Kalakanis, L., Rubenstein, A. J., Larson, A., Hallam, M., & Smoot, M. (2000). Maxims or myths of beauty? A meta-analytic and theoretical review. Psychological Bulletin, 126(3), 390-423.

10.1037/0033-2909.126.3.390.McDonald, M. G., & Birrell, S. (1999). Reading sport critically: A methodology for interrogating power. Sociology of sport journal, 16(4), 283-300.

10.1123/ssj.16.4.283.Madrigal R (2006) Measuring the multidimensional nature of sporting event performance consumption. Journal of Leisure Research, 38(3), 267–292.

10.1080/00222216.2006.11950079.Mears, A. (2014). Aesthetic Labor for the Sociologies of Work, Gender, and Beauty. Sociology Compass, 8(12), 1330-1343.

10.1111/soc4.12211.Meier, H. E., & Konjer, M. (2015). Is there a premium for beauty in sport consumption? Evidence from German TV ratings for tennis matches. EJSS. European Journal for Sport and Society, 12(3), 309.

10.1080/16138171.2015.11687968.Messner, M. A. (2002). Taking the field: Women, men, and sports. U of Minnesota Press.

Mutz, M., & Meier, H. E. (2014). Successful, sexy, popular: Athletic performance and physical attractiveness as determinants of public interest in male and female soccer players. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 1-14.

Newman, J. I. (2014). Sport without management. Journal of Sport Management, 28, 603-615.

10.1123/jsm.2012-0159.Pellizzer, M., Tiggemann, M., & Clark, L. (2016). Enjoyment of sexualisation and positive body image in recreational pole dancers and university students. Sex Roles, 74, 35-45.

10.1007/s11199-015-0562-1.Ponterotto, J. G. (2005). Qualitative research in counseling psychology: A primer on research paradigms and philosophy of science. Journal of counseling psychology, 52(2), 126.

10.1037/0022-0167.52.2.126.Riffe, D., Lacy, S., & Fico, F. (2005). Analyzing media messages: Using quantitative content analysis in research (2nd ed.). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

10.4324/9781410613424.Sarpila, O. (2013). Appearance-related consumption among dating, cohabiting and married consumers: a comparison between men and women. The International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research, 23(1), 31-47.

10.1080/09593969.2012.711257.Shafer, L. (2009). First down Dallas player, eager to debut in new Lingerie Football League. The Dallas Morning News, 17 September, 38–39.

Stake, R. E. (1995). The art of case study research. Sage.

Signorielli, N., McLeod, D., & Healy, E. (1994). Profile: Gender stereotypes in MTV commercials: The beat goes on. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 38(1), 91-101.

10.1080/08838159409364248.Urquhart, & Crossman, 1999 Urquhart, J., & Crossman, J. (1999). The Globe and Mail coverage of the winter Olympic Games: A cold place for women athletes. Journal of Sport and Social Issues, 23(2), 193–202.

10.1177/0193723599232006.Vincent, J., Imwold, C., Johnson, J.T., & Massey, D. (2003). Newspaper coverage of female athletes competing in selected sports in the 1996 centennial Olympic Games: The more things change the more they stay the same. Women in Sport & Physical Activity Journal, 12(1), 1–22.

10.1123/wspaj.12.1.1.Wallis, C. (2010). Performing gender: A content analysis of gender display in music videos. Sex Roles, 64(3/4), 160-172.

10.1007/s11199-010-9814-2.Weaving, C. (2014). It is okay to play as long as you wear lingerie (or skimpy bikinis): a moral evaluation of the Lingerie Football League and its rebranding. Sport in Society, 17(6), 757-772.

10.1080/17430437.2014.882905.Yoder, J. D. (2016). Sex Roles: An up-to-date gender journal with an outdated name. Sex Roles, 74, 1-5.

10.1007/s11199-015-0560-3.